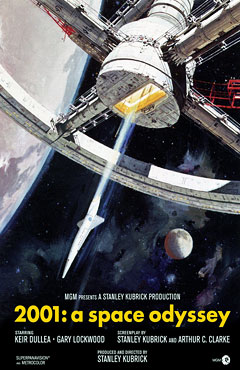

2001: A Space Odyssey

Warner Bros.

Original release: April 6th, 1968

Running time: 141/161 minutes

Director: Stanley Kubrick

Writers: Stanley Kubrick, Arthur C. Clarke

Cast: Keir Dullea, Gary Lockwood, William Sylvester, Daniel Richter

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

“How could we possibly appreciate the Mona Lisa

if Leonardo had written at the bottom of the canvas

‘The lady is smiling because she is hiding a secret

from her lover’? This would shackle the viewer to

reality, and I don’t want this to happen to 2001.”

~ Stanley Kubrick

Perhaps it was the psychedelic movement of the late 1960’s that saved Stanley Kubrick’s tale of first contact with an extra-terrestrial intelligence from being buried in oblivion. The initial response to the film was extremely polarised if not hostile, and at the box office it wasn’t a hit either. Rumour has it MGM, ready to pull the movie after a few weeks, was told by theater owners there’s more people coming to the shows at last but those people were somewhat different — a young crowd, smoking pot before the screenings.

2001: A Space Odyssey premiered in April 1968, around the same time Martin Luther King, Jr. and a few weeks before presidential candidate Robert F. Kennedy were assassinated. Eventually the year itself was turning into a catharsis of sorts for Western civilization, with anti-war protests, the civil rights movement, violent protests, the beginning of the “Flower Power” counterculture — all heralding a shift of consciousness not only in America but the world over.

Regardless of its outcome, this shift had been in the making for years with the JFK assassination contributing as an, if not the event that traumatized a nation and galvanized it into change. 2001’s co-authors Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke developed the film against a historical backdrop that may have influenced the film’s genesis more than a 21st century audience would think.

In a way, the philosophical and allegorical sub texts of 2001 had been outpaced by reality, undermining the film’s grand theme of human evolution. Possibly God has never been deader than in the late 1960’s and early 1970’s and His subsequent revival led to Kubrick’s film being revived, too — as a semi-scientific vision of a supreme being that is basically impersonal. Thus 2001 left behind a lot of the context in which the film was made and initially perceived. Like other masterpieces, Kubrick’s Odyssey was later thrust light years out of bound in terms of interpretation and cultural relevance.

Yet, 2001 remains a myth and as such endured decades, and is likely to endure “infinity”. Forgotten is the space race between America and Russia that dominated much of the mood in the 7th decade of the last century. Forgotten is the manic obsession with which America tried to overtake the Russians for years until, finally, it could make a “giant leap” for the whole of mankind — more than one year after 2001 premiered. Not surprisingly, much of what we see in the moon footage and the images of later NASA missions resembles the film’s design. Kubrick’s Odyssey may be one of the rare cases of life actually imitating art.

The visual audacity and the sparse plot of 2001 are a statement against the speed of the time. Kubrick halted everything and celebrated the virtue of contemplation. In fact, the film is a cinematic meditation in its own right and, like any meditation, has the meaning the beholder attaches to it. No less and no more. The film stands as a monument to Kubrick’s genius and still has many fans and professional admirers while it has never really penetrated mainstream culture. 2001: A Space Odyssey is the epitome of a cult movie.

It contains a prophecy — and is a message — too. Coincidentally, I watched the film in the summer of 2001, and then again in November of that year. Something had changed, like there’s a pre-9/11 way to see the film, and a post-9/11 one.

Not only because 2001 is also the story of an unresolved conspiracy. This is apparent rather soon after the — still mesmerizing — jump cut from a flying bone in pre-history to a space station a million years later. Scientists have discovered a black monolith on the  moon, an artifact put there by a non-human intelligence 4 million years earlier. The discovery is not shared with the public but kept in total secrecy — including an embarrassing cover story — by an enigmatic “council”.

moon, an artifact put there by a non-human intelligence 4 million years earlier. The discovery is not shared with the public but kept in total secrecy — including an embarrassing cover story — by an enigmatic “council”.

The council’s envoy, Dr. Heywood R. Floyd explains the reason for the secrecy to the insiders:

“I’m sure you’re all aware of the extremely grave potential for cultural shock and social disorientation contained in this present situation if the facts were prematurely and suddenly made public without adequate preparation and conditioning. Anyway, this is the view of the council.”

In the early 1960’s, this kind of monopolized knowledge was common practice — cold war, space race, an ever-latent nuclear war — and it’s likely to take decades or longer before we learn the true history of that era, if at all. However, since World War II the world has been ruled by secrecy in large parts. It seems fair to assume there are discoveries and developments we haven’t and maybe won’t learn about in our lifetimes.

There is an omnipotent but subtle layer in Kubrick’s Odyssey, one that has a rather down-to-earth relevance to this day. The monolith in the film — thought  of as a “teaching machine” (A.C. Clarke) triggers an evolutionary leap in man and has been interpreted by some as the notoriously famous Philosopher’s Stone with all its alchemical traits.

of as a “teaching machine” (A.C. Clarke) triggers an evolutionary leap in man and has been interpreted by some as the notoriously famous Philosopher’s Stone with all its alchemical traits.

The monolith appears four times in the film: in pre-historic times where it seems to trigger the tool-making ability in man, then on the moon a million years later when it sends out a shrieking tone virtually paralyzing its observers, then a third time around Jupiter and finally at the end, when astronaut Bowman reaches out for it a last time. Finally the camera zooms in on it until the screen itself becomes the monolith.

This takes the viewer full circle as the film starts with a black screen on music — lasting for more than 2.5 minutes. In a way, we ourselves touch the monolith right from the start, a black and mysterious surface that seems to represent a gate to ultimate knowledge.

Is the monolith a message? I think it is. Knowledge has always been the most valuable asset — not only in man’s evolution. Monoliths, like pyramids, are core symbols of religious and metaphysical history and almost ever refer to a higher knowledge too, one that can be used in both benign and destructive ways.

What’s more, we have to “get in touch” with that knowledge in order to thrive as human beings. Whether or not Kubrick refers to Nietzsche’s Thus Spoke Zarathustra with its conclusion that modern man is the link between ape and “Übermensch”, enlightenment is something that can fall victim to “adequate conditioning” by forces that can and do monopolize knowledge.

Kubrick had a reputation for being an excellent people manipulator. Some making-of stories and anecdotes about the production of 2001 imply a kind of disconnect between Kubrick and Clarke as well as between Kubrick and the rest of cast and crew. According to eyewitnesses, Kubrick’s apparently eccentric behavior during the production might point to him just being a perfectionist and a filmmaker who closely guarded his absolute creative independence.

Nonetheless, Kubrick could well have implemented “hidden” clues none of which anyone involved in the production may have been aware of. It’s said that he was closely connected to people “in the know”, not only because of A.C. Clarkes relationship with NASA (Kubrick himself called Clarke “the scientifically best-informed writer”).

Kubrick was considered to be one of the most independent filmmakers who could virtually do what he wanted. I doubt this was due only to him being a genius director, writer and producer whose films made money. There have been others who still didn’t enjoy anything near Kubrick’s creative freedom. It seems plausible that his exceptional position had other reasons, too.

So do the circumstances surrounding the production of 2001, starting with the film title. Originally called “Journey beyond the Stars”, Kubrick later autonomously decided to change the title and implement 2001. On the surface the film has nothing to do with the year 2001 apart from it being the first year of the new millennium and having some religious meanings. If it is true that nothing in Kubrick’s films is coincidence, the relevance of 2001 becomes even more intriguing.

Assuming that Kubrick has threaded a sub-text into the film only people with the right mindset would be able to see and understand, was it a message or even a warning? Almost everything in 2001 was “scientifically correct” (something Kubrick insisted on) but apparently there were still “facts” Kubrick interspersed nobody thought possible.

“The one episode in the film which I thought improbable, and this was Stanley’s idea, not mine, was HAL lip-reading. Well, now they are training computers to lip-read so Stanley was right and I was wrong.” ~ A.C. Clarke

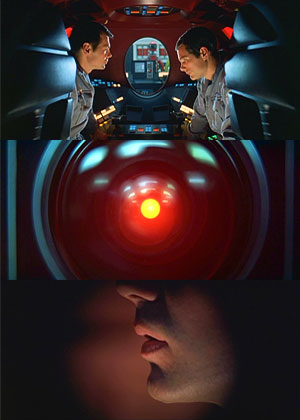

This episode happens on Discovery One, the space ship carrying five astronauts to Jupiter where the conundrum of the monolith could be solved. 3 of the astronauts are in  hibernation while 2 of them see to the routines on board. The heart and mind of the ship is an super-intelligent computer, the ubiquitous HAL.

hibernation while 2 of them see to the routines on board. The heart and mind of the ship is an super-intelligent computer, the ubiquitous HAL.

When the 2 astronauts realise HAL may have made a mistake they withdraw into one of the space pods in which they normally leave the ship. Assuming HAL wouldn’t hear them inside the pod, they discuss HAL’s behavior and decide they might have to switch him off. HAL, however, reads the lips of the astronauts and knows what they’re up to. His reaction is human. Seemingly paranoid and overwhelmed, he plots to get rid of the astronauts. HAL kills all of them, apart from Bowman, who ultimately manages to take him offline.

Aside from the myriad of views on artificial intelligence, the question is whether HAL’s failure was a just malfunction or a deliberate act of sabotage, pointing back to a conspiracy. The film doesn’t explain what the “council” is or who represents it. It sounds more like a “powers that be” version — people who pull the strings behind the scenes.

After all, no one knows what kind of intelligence the mission will encounter, and given the “grave potential for cultural shock and social disorientation” the council couldn’t afford to jeopardize the status quo. The reactions of the five astronauts are not predictable either, were they to meet the “aliens”. Who can be sure if they would keep it secret? Lastly, sacrificing lives for a “higher purpose” is nothing new in history and given the opportunity, the “council” might just do it.

“Stanley was specifically interested in the possibility of life in outer space, and what would happen if we encountered it or it encountered us. That was the basic theme he was interested in.” ~ A.C. Clarke

The story of 2001 is also one of change and even implies the creation of a new species with unforeseeable implications. If such a change is imminent, the elites would have everything to lose. The state of the world in the 1960’s was such that even extinction seemed like a real possibility. We only need to imagine what happened if the powerful of this world learned of a long-term threat to their reign. Obviously, they would take long-term measures.

Whether or not they would succeed is a whole other question. At the end of 2001, we experience the dawn of a new era — but not only that. Originally Kubrick intended to introduce  actual aliens but ran out of time and money. The substitute was a room an extra-terrestrial intelligence might create to welcome a human being.

actual aliens but ran out of time and money. The substitute was a room an extra-terrestrial intelligence might create to welcome a human being.

But there is no contact. Instead we see Bowman grow old quickly and regress into the “star child” that apparently returns to Earth. There are certainly countless ways to interpret the metaphysical sub text of the film’s ending, but over the years I’ve come to see it as a negation of time, as in time does not matter at all. The eternal circle of life and with it any leaps in evolution appear marginal when put in the context of “infinity”.

Kubrick’s message? He might have known something or, as the visionary he was, foreseen a development that would concern history a few decades on in the early 21st century. Whatever it is, the “powers that be” may have been working on it for ages and the slow progress of their agenda is making it possible to withhold knowledge as they see fit and thereby concealing a perpetual process of ”adequate conditioning”.

At this point, something else is emerging out of the volatile subtexts of 2001. Its impenetrable theme forest of abstract scientific ideas, the origins and the future of mankind, life in outer space, evolution and artificial intelligence begin to clear up, only to give way to a message that seemed to be hidden in the film all along.

- Paul Joyce, 2001: The Making of a Myth, TV documentary aired January 13th, 2001

- Stanley Kubrick, Interview with The New Yorker (November 27th, 1966)

- Thomas D. Clareson (Editor), SF: The Other Side of Realism, Bowling Green University/Popular Press, 1971

The more so as the film doesn’t seem to have a true ending at all — it concludes a cycle of evolution but leaves open how this cycle ends. Behind the stunning imagery lies a foreboding of something hopeful but dark, and everything seems to depend on our knowing. This might not have been relevant up until 2001, but as though Kubrick knew or envisioned in 1968, our survival might depend on it quite soon after the new millennium has begun.

Jonahh Oestreich

One of the Editors in Chief and our webmaster, Jonahh has been working in the media industry for over 20 years, mainly in television, design and art. As a boy, he made his first short film with an 8mm camera and the help of his father. His obsession with (moving) images and stories hasn’t faded since.

You can follow Jonahh on Twitter @Jonahh_O.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA