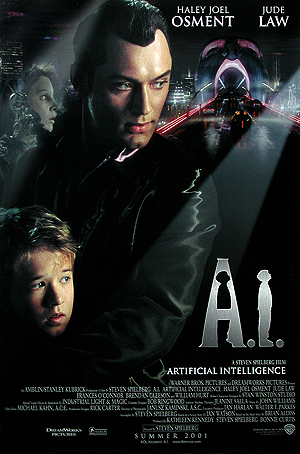

A.I. Artificial Intelligence

DreamWorks Pictures

Original release: June 29th, 2001

Running time: 146 minutes

Director: Steven Spielberg

Writers: Steven Spielberg, Brian Aldiss, Stanley Kubrick

Composer: John Williams

Cast: Haley Joel Osment, Jude Law, Frances O’Connor, Brendan Gleeson, William Hurt

The Super Mechas 01:50:55 to 01:56:35

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

It’s the late 21st Century and the world is no longer our own. The oceans have risen up and taken over the land. New York, once the summit of man’s achievements, is submerged, its skyscrapers barely peeking above the surface of the water, its amusement parks drowned like tacky Antlantises.

Man has moved on though, and discovered a new achievement: life. Buildings are easy – bricks and mortar moulded into an appropriate shape. But what about flesh, bone and everything in between? How do you construct a soul? How do you build an emotion? How do you make a human being?

That’s the question Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg seek to answer in A.I. Artificial Intelligence, a film that confounded critics when released in 2001 but which is now slowly gathering a reputation as one of the most profound and important films of the last decade. It’s a deserved reputation too, because A.I. goes about answering its central question with unsettling ambiguity and a deeply affecting melancholy.

For the film’s instigator, brilliant scientist Professor Hobby, humanity is a simple question of emotion. The film opens at a robotics seminar during which Hobby asks his audience to consider the existence of a robot who could love and feel. He exhibits the lack of progress on this issue by stabbing the hand of his robot secretary. She recoils.

How did that make you feel? Angry? Shocked?

SECTRETARY:

I don’t understand.

HOBBY:

What did I do to your feelings?

SECTRETARY:

You did it to my hand.

The secretary has failed to translate the physical feeling into an emotion, so Hobby creates something that can – a robot boy called David who walks and talks and lives and breathes like a human being. He feels pain, and understands it on an emotional level, and once his parents active a code, he will love them unconditionally until his software corrupts and his hardware erodes. Not only has Hobby created emotion, he’s also discovered perfection.

But is perfection what humanity is? A.I.’s organic humans cast doubt on that idea. Each of the film’s humans is flawed, Hobby (ironically) more than most. He’s a bereaved father who, we discover later, was in part motivated to create David to heal the hurt from losing his son. In creating David, Hobby was working out of weakness, pain and tragedy. David’s creation is, ultimately, an act of selfishness.

David’s adoption by his ‘parents’, Monica and Henry Swinton, is no less selfish. Like Hobby, they’re grieving too – their son Martin is in a coma and his outlook seems bleak. David numbs the pain, giving the Swintons a replacement they can love and who can love them in return. For both Hobby and the Swintons, David is just an object to serve their needs.

These thoughts are echoed by Gigolo Joe, a love mecha David meets when he’s forced to go on the run after being abandoned by the Swintons following Martin’s resuscitation.. David is desperate to return to his mother, but Joe explains some harsh truths about humanity’s relationship with their creations:

Of course, humanity’s end does come, but our legacy doesn’t end with us. The film’s conclusion is set hundreds of years into a future where humans have died out and the water that swept across the land has frozen into ice. Mechas have evolved, becoming hyper-intelligent Super Mechas, and they excavate the ice hoping to discover remains of what came before them. They’re looking for their creators, just as we look for ours.

Indeed, these Super Mechas desire nothing more than to become human, but why? This question lingered over Kubrick as he wrestled with the film’s script before passing it on to Spielberg. In the book A.I. Artificial Intelligence, notes sent between Kubrick and screenwriter Ian Watson are published, and they give the following reason for robotkind’s bid for humanity.

Humanity for Kubrick and Watson then is partly about creation. The Super Mechas achieve this at the end of the film when they use David’s memories to resurrect Monica (or, at least, a temporary hologram of her) and grant his wish to be reunited with her. Yet this is still not humanity – they bring Monica back to study and learn from David’s reaction to her as to please him; it’s an attempt to learn more about humanity and love. Their quest, it seems, continues. Or does it?

The scene depicting their trawl through the ice is arguably the film’s highpoint. Spielberg’s camera glides across the frozen wasteland as John Williams’s ethereal score fills the soundtrack. A ship, made of metal blocks held together by nothing more than energy, makes its way across the ice and finally comes to rest in the remains of Coney Island, where a giant Ferris Wheel has trapped David.

The scene possesses a sort of religious wonder. David almost becomes born again, emerging from his frozen, white amphibicopter and being greeted by the Super Mechas who resemble Gods, elegantly moving across the ice in complete control of David and the world around them. They search the boy’s memory, looking for life, looking for humanity.

- [1] A.I. Artificial Intelligence – From Stanley Kubrick to Steven Spielberg: The Vision Behind The Film, Jan Harlan and Jane M. Struthers. Thames and Hudson, 2009.

The Super Mechas (and, to an extent, David) have become like Hobby and the Swintons – creating out of love, but exploiting living, thinking creatures to feel that love. They too have become flawed and selfish, and this, the film argues, is what humanity is. Not the perfection that Hobby seeks at the start of the film, but imperfection, moral ambiguity and irony.

As technology continues to develop and our lives become ever more streamlined – and ever more perfect – because of it, A.I., and particularly this scene, serves as a timely reminder of what humanity really is. We’re not the perfect beings we aspire to be or the infallible computerised systems we hope to build. We’re selfish and flawed creatures, small and vulnerable, looking for someone we can love and feel love from in return.

Paul Bullock

Paul fell in love with cinema when dinosaurs ruled the Earth. A childhood viewing of Jurassic Park introduced him to the power and wonder of the silver screen, and after his dreams of directing were shattered by crumbling papier-mâché sets, disobedient action figure actors and a total lack of talent, he quickly turned to writing, thus proving that life does indeed find a way.

When not citing scripture from the apostle Ian Malcolm, Paul also enjoys the films of Billy Wilder, Paul Thomas Anderson, Stanley Kubrick, Frank Capra, Martin Scorsese and Werner Herzog. His favourite film is The Apartment and his favourite apartments are in films. They're much cleaner than his.

Paul can also be found talking nonsense on Twitter and his website Quiet of the Matinee. He works through his addiction to a certain bearded director on From Director Steven Spielberg.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA