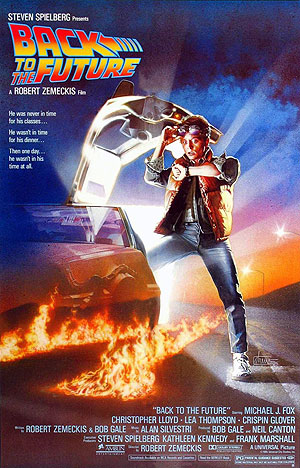

Back To The Future

Universal Pictures

Original release: July 3rd, 1985

Running time: 116 minutes

Director: Robert Zemeckis

Writers: Robert Zemeckis, Bob Gale

Composer: Alan Silvestri

Cast: Michael J. Fox, Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, Crispin Glover

Breakfast scene: 0:14:00 to 0:16:43

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

Back To The Future is a film I’ve come back to time and time again since I first watched it when I was 5.

Having been born in the very late 80s, at a young age I didn’t have any real idea of what it was to be in that era. Prior to having the internet, I’d heard stories from my parents and seen old photos…. and Back To The Future.

It wasn’t just the depiction of an incredibly cheesy 80s world – Huey Lewis providing the backbone of the soundtrack, which ironically was also used for a much darker depiction of the 80s in American Psycho – there something else I clung onto with this film – something that struck me more than just an entertaining story.

Obviously time travel is a cool concept, whether you’re 5 or 75, it’s something we’ve all dreamt of at some stage. The beauty of time travel could be to right a wrong, relive a great moment or understand a culture or era that was previously out of reach to us.

During his time travel experience Marty (Michael J. Fox) rights a wrong (from a wrong that he made himself in the process of trying to right a wrong) and comes to see what life was like for his parents when they were growing up. This experience grants him something that’s impossible for everyone else of his generation; to witness the 50s first hand.

From the start of the film, though, I always felt an affinity with Marty. He was oblivious to the era that preceded him, the era that made him. He’d heard the stories, seen the photos and the old television shows but he didn’t understand what it was to have lived in the 50s, as he comes to later on in the film. The 50s were to Marty what the 80s were to me; a construction of ideas, but with nothing tangible to cling onto.

Where my affinity turns to jealousy is when Marty has the opportunity to experience that era – something which, unless time travel is invented, I will never have the chance to do.

The scene that strikes me is one of the few moments of family life for Marty – his family as he understands them up until Doc (Christopher Lloyd) goes and invents time travel. The family breakfast scene sets the perfect foundation for the rest of the film.

I think it’s terrible. Girls chasing boys. When I was your age I never chased a boy, or called a boy, or sat in a parked car with a boy.

LINDA:

Then how am I supposed to ever meet anybody.

LORRAINE:

Well, it will just happen. Like the way I met your father.

LINDA:

That was so stupid, Grandpa hit him with the car.

LORRAINE:

It was meant to be. Anyway, if Grandpa hadn’t hit him, then none of you would have been born.

LINDA:

Yeah, well, I still don’t understand what Dad was doing in the middle of the street.

LORRAINE:

What was it, George, bird watching?

As the film continues and time travel ensues, it’s pretty clear that Marty’s mother (Lea Thompson) was quite the boy-chaser and his father (Crispin Glover) wasn’t ‘bird watching’, in the conventional sense anyway. The prophetic fallacy it’s setting up is  almost painful in hindsight when he later meets his father, the peeping-Tom, and his mother, the horny-drinking-smoking young lady.

almost painful in hindsight when he later meets his father, the peeping-Tom, and his mother, the horny-drinking-smoking young lady.

It’s the loving affection with which his mother throws out the story of how they first met and the daughter’s bored retort that hits home:

Yeah Mom, we know, you’ve told us this story a million times. You felt sorry for him so you decided to go with him to The Fish Under The Sea Dance.

LORRAINE:

No, it was The Enchantment Under The Sea Dance. Our first date. It was the night of that terrible thunderstorm, remember George? Your father kissed me for the very first time on that dance floor. It was then I realized I was going to spend the rest of my life with him.

Marty’s understanding of his parents and the time they grew up in stem from the stories they tell about how they first met – stories that have become mundane because of how often they’re told, but stories that were life changing events for their parents, and were the cause of the lives of their children. These stories are stale and worn; they have little relevance to the kids in this modern era of theirs.

Their stories, however, create a specific picture of their own histories; one that Marty’s experience comes to contravene. Hayden White’s essay The Historical Text as Literary Artifact discusses how ‘a scholarly field takes stock of itself […] by considering its history’ , and although the McFly’s lives aren’t necessarily a scholarly field, this is one way of looking at how we come to understand ourselves and others.

We tell stories to explain and understand, but when it’s an individual’s life story it  becomes more about how the stories are told, and what they say about the person rather than the content of the stories themselves.

becomes more about how the stories are told, and what they say about the person rather than the content of the stories themselves.

White goes on to say that the purpose of meta history is to solve questions such as:

The only understanding of their parents’ history and, consequently, the 50s has been from their own historical accounts – much in the same way as my understanding of the 80s stems from the same stories told by my parents. The question of authority and reality stand out when put against the old stories that Marty’s parents tell; the romanticism of how they met is brought into disrepute when we see what actually happened, but the truth of the matter is it’s a reality that his parents have come to know and love.

Without questioning the nature of reality itself, there’s a lot to be said for the individual constructing their own reality through their own narratives.

The authority of the McFly’s stories is destroyed when his father falls out of his tree and his mother basically falls out of her dress, but it’s much more about how they see themselves, rather than how it all actually happened. Their construct of the 50s would vary dramatically to someone else’s, but that’s the version that they’ve passed onto their kids.

What becomes interesting later on in the film is the impact Marty has on his parents and how that influences their life together. What their historical account says about their own characters, and how they remember themselves, are what culminates in the first version of them in the 80s; with Marty’s bullied father and his sullen vodka-drinking mother.

When Marty intervenes and gives his father the confidence to stand up for himself, the entire dynamic of their family changes forever. His father becomes a stronger character and manages to dominate Biff, where before he’d only been subservient to him. The minor change in history inevitably has an impact on the McFly’s historical accounts of themselves, how they perceive themselves and each other, and brought a much happier reality to the 80s.

- White, Hayden, ‘The Historical Text as Literary Artifact’ in The History and Narrative Reader (2001), ed. Geoffrey Roberts, Routledge ¹

Time travel films tend to have the same trope of ‘any changes to the space-time continuum will result in terrible consequences’ – but not in Back To The Future; Marty saves the day in every respect of the manner, and is a hero by the end.

What I’ve learnt from Back To The Future is that meddling in the 50s is fine, as long as you come out on top – which is more than I can say for the Biff family.

Jack Murphy

Jack is an English Literature student in his early Twenties (The Golden Age!) at the University of Leeds. He insists on saying that he’s originally from Slough, Berkshire which is the setting of Ricky Gervais’ comedy series The Office – and not a day goes by that he’s not reminded of that fact… Irrespective of being mocked for it, Jack still is, and will most likely remain, a big Gervais fan.

And he sure knows how to spend his time. Having subscribed to a well known DVD delivery service for the past three years, Jack spends half of his days watching DVDs – and the other half on catch-up websites watching TV programmes.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA