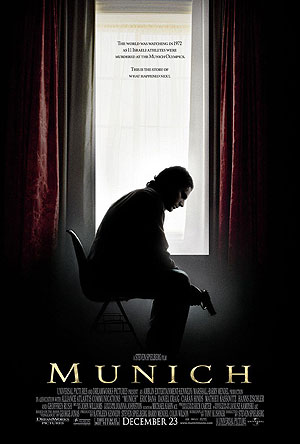

Munich

DreamWorks

Original release: December 3rd, 2005

Running time: 163 minutes

Director: Steven Spielberg

Writers: George Jonas, Tony Kushner, Eric Roth

Composer: John Williams

Cast: Eric Bana, Daniel Craig, Ciarán Hinds, Mathieu Kassovitz, Hanns Zischler, Geoffrey Rush

World Trade Center 02:26:30 to 02:37:05

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

Where should allegiances lie in times of national crisis? Avner Kaufman (Eric Bana), the protagonist of Steven Spielberg’s Munich, is faced with this dilemma following the murder of eleven Israeli athletes at the 1972 Munich Olympics by Palestinian terrorist organisation Black September. As an agent for the Mossad (the Israeli intelligence service), he must make a snap choice between standing by his family or helping his nation get revenge by whatever means necessary.

Avner agrees to lead a clandestine mission to assassinate eleven high-ranking members of Black September and the Palestine Liberation Organization based in Europe. The personal toll of the mission is exposed as he must learn to act and kill like a terrorist and run his five man team as an independent terror cell secretly funded by the Mossad.

What haunts me most though about Munich, having recently become a parent myself, is how this critical phase of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict is portrayed in terms of ‘beleaguered individuals with families’. Having never personally dabbled in anything that could be called a career, I’ve been able to enjoy paternity leave and be present for those priceless tiny moments as my daughter plunged headlong from newborn to toddler in a wonderful and terrifying blur. Just as Avner is about to become a proud parent, he must leave his wife behind in Israel for a mission which could last for months or even years.

In addition to the high price on a personal and familial level that Avner pays for his decision, the ramifications on a global stage are addressed as the film’s narrative connects the Munich massacre to the attacks on 11th September 2001 in what David Clay Large describes as an ‘arc of terror’.

The hostage siege and failed rescue attempt at Munich was the first terror event watched live by a global audience, and this invasion of the domestic space by the specter of terror is represented by the darkness of Avner’s living room.

We first see Avner in close-up from a low angle, the glow radiating from the television screen giving him an expressionistic mask of grief and anger for the murdered athletes (whose funerals he’s watching coverage of) and also inner turmoil at the thought of being caught up in the massacre’s aftermath. The living room is further invaded through Munich‘s use of editing as footage of Avner hearing a roll call of the eleven dead athletes’ names is inter-cut with Israeli military chiefs in a bunker identifying the eleven Palestinians targeted for assassination.

In stark contrast to the gloom of the living room is the brightly lit kitchen, a space repeatedly used in Munich as a signifier of family love and provision. Daphana, Avner’s wife, emerges from the kitchen and joins Avner in front of the television, also sensing that he will be called up for duty. Avner attempts to reassure her that this won’t happen but an impending separation from his family is hinted at by his inability to leave the living room and enter the kitchen.

He instead ends the scene in silhouette, stood in the entrance to the kitchen, caught between the light (representing his future role as parent) and dark (his future role as state-sponsored terrorist). The scene concludes with Avner stressing that his number one priority is their impending child. This sentiment is proved hollow as this domestic unity will soon be yet another victim of the Israeli/Palestinian conflict.

Compounding this loss is the knowledge that Avner is repeating his parents’ mistake of neglecting his own family for the service of Israel, as well as damaging other family units in this service. The majority of the mission’s targets are middle-aged family men which his team kill using bombs placed in a variety of domestic household items (including a bed, a telephone and a television). In doing so, the actions of Avner’s team are continuing the foregrounding the family and its domestic setting as a site of terror.

The price that Avner pays for accepting the mission is laid bare in Munich’s conclusion. Reflecting the entrenched nature of the Israeli/Palestine conflict, there is no resolution for the mission which is terminated incomplete. Each of the seven targets killed has been replaced with a more dangerous and extreme character, every ‘success’ for Avner’s team draws increasingly violent  responses from Black September – a campaign of letter bombs, a hi-jacked airliner, a massacre at an airport – establishing a dialogue of violence claiming countless innocent lives and banishing any hope of peace for generations.

responses from Black September – a campaign of letter bombs, a hi-jacked airliner, a massacre at an airport – establishing a dialogue of violence claiming countless innocent lives and banishing any hope of peace for generations.

Like a revenger in a Western, Avner concludes the narrative unable to settle in the society he’s sacrificed so much for. Finding nothing heroic, cleansing or redemptive in his violent actions, he denounces Mossad’s programme of targeted assassinations as murder and joins his wife and his young daughter living in exile in New York.

Munich‘s final scene, like the majority of the film, is drained of vivid colours and is bleak in tone. Avner is visited by Ephraim, his contact from the Mossad and they meet in the liminal space of the Brooklyn shoreline. Ephraim finds Avner a shadow of the man who started the mission, plagued by the fear that his family are now being targeted by a Mossad hit squad and that all he achieved was making the world a more dangerous place. Ephraim tells him that he killed for peace, to which Avner spits back, ‘there is no peace at the end of this’.

The two men stroll into a deserted and seemingly neglected children’s playground, a location which signifies the damage done to Avner’s family through his transformation from family man into killer. Ephraim tries one last time to get Avner to return to Israel, emotionally blackmailing him by telling him he’s abandoned his sick father and lonely mother. Avner refuses and the two men exit the playground in opposite directions, signifying a permanent separation between Avner and his ‘mother’ land.

- Munich 1972: Tragedy, Terror, and Triumph at the Olympic Games, David Clay Large, 2012

As with the majority of Spielberg’s films, Munich can be boiled down to a family melodrama but uniquely amongst this body of work there is no redemption and no happy ending. Despite his best intentions, by accepting the mission Avner ensured that he will never again find peace within himself or his family life.

It’s in the final shot that the connection between Israel’s response to the 1972 massacre and 9/11 is made explicit, completing the ‘arc of terror’ that frames Munich. As the crane shot climbs the playground it comes to rest on the East River and the sky scrapers of Manhattan. Like a ghostly apparition in the haze of the city, and echoing Avner’s comment of ‘there’s no peace at the end of this’, is a computer generated representation of the twin towers of the World Trade Center. Their presence at the centre of the final shot of the film suggests that a chain of events is under way that will result in their destruction, posing audiences uncomfortable questions regarding America’s response to 9/11 and how it threatened to generate ever widening cycles of violence in which every act is an act of revenge.

Ian Roberts

After spending the last ten years playing in bands and promoting electronica nights in Winchester (Hampshire, UK), Ian combined his love of film and music by co-founding SuperCool Cinema, a pop-up cinema specialising in live soundtracking and double-bills of cult classics old and new.

SuperCool cinema’s modestly sized film blog has also enabled him to carry on writing since completing his Master of Arts in Film Studies, highlights of which include his epic thesis on 21st Century revenge cinema and leading a group reading of the opening twenty minutes of David Lynch’s Inland Empire.

Put a gun to his head and demand to know his favourite three films and he would say 2001: A Space Odyssey, Robocop and Fargo but then follow you around saying that he was maybe considering swapping Fargo for The Fly or Notorious until you got your gun out again.

You can follow Ian on Twitter at @SuperCoolCinema and on Facebook.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA