Triumph Of The Will

TRIUMPH OF THE WILL (DOCUMENTARY)

Leni Riefenstahl-Produktion

Original release: March 28th, 1935

Running time: 114 minutes

Country of origin: Germany

Original language: German

Director: Leni Riefenstahl

Writers: Leni Riefenstahl, Walter Ruttmann

Cast: Adolf Hitler, Max Amann, Martin Bormann, Walter Buch

Throughout the 1930s, there were many cartoons, party documentaries and political promotional items made, designed to remodel a progressive Germany which would steady its economy and elevate itself to the crest of international rightwing politics. I always recommend Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph Of The Will purely because it encapsulates that very idea and embodies the era of Nazi propaganda. Other structures in the West, particularly in the North America education system, had already been embedded through the power of markets and advertising, but the Third Reich was so engorged with political might, it made these attempts seem trivial.

The first time I watched Triumph, I felt anxious. It’s easy to see why it won so many awards for cinematography and remained the exemplar of Nazi filmmaking right up until the collapse of the Third Reich. In a strange way you find yourself sympathising with the content. As a piece of propaganda, it’s compassionate, painting Germany as a nation regaining its place, power and utility in between economic depression and war. Its sentiment is unifying and magnetic, and you feel corrupt for enjoying it. This is testament to Riefenstahl’s ability to control us with images, as the film contains very little dialogue, only small extracts of galvanising oration from Hitler and his countrymen at rallies across Germany. In effect, it is a footage feature of marching infantry, saluting workmen and state mobilisation.

I remember reading an old Adolf Hitler quote which characterised how pervasive the idea of a regenerated Germany was before the Second World War – and in a sense it exemplifies how difficult it is to see past this propaganda:

“The most striking success of a revolution based on a philosophy of life will always have been achieved when the new philosophy of life as far as possible has been taught to all men and, if necessary, later forced upon them…”

The question which springs up is: how was this philosophy forced upon them?

Naturally, it was through political capacity, but The Nazis, condemned as deceivers, aggressors and totalitarians throughout history are vital to deciphering how coercion is instituted through images. In Riefenstahl’s Triumph, it’s interesting to note how she designed an early film aesthetic around the swastika (what Hitler called “a token of freedom”). It became her summoning leitmotif, stitched to the uniforms of soldiers, labourers and politicians throughout her film. It’s ubiquitous in Triumph, which in itself is a fiercely rousing portrait of Nazi Germany, bound to the concepts of customary national pride, strength and conviction – all of which are perilously persuasive. The swastika was emblematic of them all.

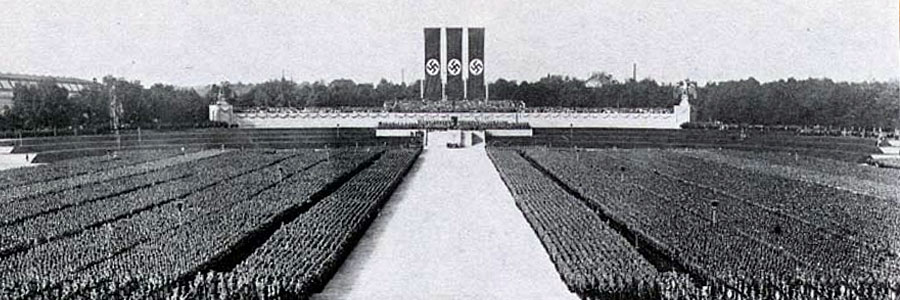

What’s telling though is how Riefenstahl developed her aesthetic knowledge. She started her film career working with Arnold Fanck, a well-known “mountain film” director. They explored the idea of Teutonic heroism conquering nature, a signal towards the human ego which appealed to Hitler in all its wildly triumphant glory. She found traction in 1933 after making Victory Of Faith, a short film about the Nazi congress and was able to tie folkloric structures to the grand narrative of Reich politics. The two primary reasons as to why Riefenstahl’s Triumph was so epic? She was the first person to ever make a film during the Nazi regime  without the involvement of Goebbels and she was also a pioneer of aerial photography, able to capture vast landscapes and military formations, the likes of which had never been seen on camera before. She was redefining documentary film with each shot and we can’t help but feel an overwhelming sense of respect and admiration for the cinematic techniques.

without the involvement of Goebbels and she was also a pioneer of aerial photography, able to capture vast landscapes and military formations, the likes of which had never been seen on camera before. She was redefining documentary film with each shot and we can’t help but feel an overwhelming sense of respect and admiration for the cinematic techniques.

Relating this back to the propaganda of Triumph, Riefenstahl exhibited a remarkable ability to depict reward and duty. There are scenes of jovial brotherhood in the military camps as soldiers play football and youths play-fight, and we start to overlook how many times German flags wave in the background or how many children wrestle to get to the front of the crowd. Riefenstahl suggests that the Nazi party is something we would be lucky to join, practically deifying it. She’s methodical, vigilant and alert when constructing her narrative and often skips from momentous valedictory cries to solemn shots of buildings or statues, providing a warm juxtaposition between mass assembly and pensive calm. Influence is the magic ingredient to any successful establishment; Riefenstahl is able to normalise Nazi government without thinning it.

- Hoffman, Hilmar; Broadwin, A. John et al. 1996. The Triumph of Propaganda: Film and National Socialism, 1933-1945 Berghahn Books [Accessed October 5 2012]

- Cosner, Shaaron and Cosner, Victoria. 1998. Women Under the Third Reich: A Biographical Dictionary [Accessed October 5 2012].

It’s without doubt that Riefenstahl was the mother of Nazi imagery and aesthetic tactics. The weight of a single picture – a swastika, a rifle, a hand gesture – contained an essence which words couldn’t articulate. Since then, we’ve placed much emphasis on images to divulge tales of hardship and oppression, famous examples including the Black Pride salute in the 1968 Olympic Games or the Unknown Rebel in Tiananmen Square, 1989. There are of course countless others.

What does linger is our inextinguishable desire for documenting causes, whether through investigative journalism, social media sharing, adverts or symbols. We’re slaves to the power of the image, to its effectiveness and inherent capacity for storytelling. Triumph Of The Will, among other things, is about our need to retain our own consciousness, and one of the ways we can do that is through iconography and memorialisation.

Andrew Latimer

Andrew started out writing theatre reviews in Edinburgh while studying for a degree in Arts Journalism. His interest in film came after attending several festivals across the UK. In particular, he discovered a love of documentary cinema, specifically the work of Werner Herzog and Errol Morris.

Andrew loves films which investigate stories of undocumented struggle and solitude. Some favourite docs include Grizzly Man, King of Kong, 5 Broken Cameras, L'encerclement, Inside Job and Shoah.

Andrew runs a Scottish arts review website, TVBomb, and you can follow him on Twitter at @ajlatimer.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA