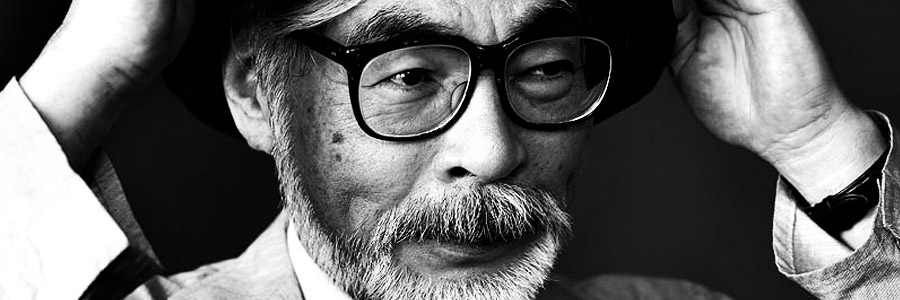

Hayao Miyazaki

One of my earliest movie memories is watching My Neighbour Totoro (1988) with my sister at my dad’s house. I was young enough to think dust bunnies were real, miniature black rabbits, and I spent some time afterward under the bed trying to find them.

I’ve had a soft spot for Hayao Miyazaki ever since. He creates beautiful, innocent, absorbing worlds; rich in themes, plot and character, that have been held close to many people’s hearts for decades.

Miyazaki’s films are undoubtedly his own, with recurring themes in both artistic style and content. They include pacifism, environmentalism, and feminism, and they’re wrapped in such beautiful landscapes, backed with what look like meticulous watercolour creations.

Hayao Miyazaki, Getty Images (2009)

He developed his style as a teenager, working in animation companies before setting up Studio Ghibli with Isao Takahata in 1985. Together, they’ve written and directed some of the films that have defined, not only my childhood, but my adolescence as well.

Miyazaki creates innocent and whimsical stories, such as My Neighbour Totoro and Pom Poko (1994), and supplies them with meaty substance – full of wholesome morals and ethics, without ever being too preachy.

In My Neighbour Totoro, he gives us Mei, a young girl who feels a bit lost and lonely while her mother is in hospital, and feels ignored by her older sister, Satsuki. Mei runs off to have an adventure by herself, and finds solace and adventure in the deep embrace of the forest. When she gets into trouble, Totoro sends the Cat Bus to rescue her.

Totoro is huge, caring and comforting – exactly the kind of company Mei and Satsuki need. Miyakzaki shows us the woodland is hugely important for children, and we shouldn’t be afraid of it. Even in the rain, Totoro can have fun with Mei and Satsuki, and the image of him with the leaf on his head, as a rain hat, is one that always makes me smile.

My Neighbor Totoro (1988), dir. Hayao Miyazaki

In both Pom Poko and Princess Mononoke (1997), Miyazaki depicts the tension between the traditional national environment and the human effects of expanding consumption. Even though the nature sides of the story are given magical powers, they’re still not impervious to human destruction.

Miyazaki tells us even the strongest things can be vulnerable, and without care and attention, can be spoiled before we know it. There’s a strong emphasis on working together and finding a harmony between the two seemingly opposing parties, as he strives to bring us a middle ground.

Ayumi Suzuki says in Animating The Chaos, Miyazaki is

He looks at the world, and uses his films to speak to us, to show us what he wants to change and put right.

Princess Mononoke (1997), dir. Hayao Miyazaki

Despite this potentially depressing note, we’re given worlds in which everything feels like it’s going to be OK if we want it to be so. Towards the end of Pom Poko, the tanuki (anthropomorphic racoon-dogs) are beginning to assimilate into the human world. Their habitat has been eaten away, but a few tanuki can still be seen darting around. The scene pulls out to show the woodland idyll is actually a manicured golf course. We’re asked to be mindful of the environment, as it’s an animal’s home. Miyazaki asks us to think and to care – we can make a difference.

With an innocent take on the world, Miyazaki doesn’t shy away from how sad it can be for a child… how lonely and unjust it can seem. The worst thing in the world is no one wanting to play with you, or getting yelled at. Miyazaki takes those children in need, be it Mei, or Sosuke in Ponyo (2008), and gives them the friends that they need. Few things make me sadder than loneliness, especially in children, and it’s a real comfort to see that an adult not only recognises this, but wants to step in and provide them with the magical companion they so desperately crave.

Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), dir. Hayao Miyazaki

Miyazaki also shows how children, while vulnerable, are able to stand up on their own and make those tough calls in life. In Kiki’s Delivery Service (1989), we follow Kiki as she heads to the city on her own as a rite of passage. She has to make her own way in the world without the safety net of her parents, friends or family.

There are several strong, young, female leads in Miyazaki’s portfolio. From Kiki, to San in Princess Mononoke, to Chihiro in Spirited Away, to Ponyo – the girls are shown in a favourable light. They are strong and independent, and can firmly rely on themselves to save the day.

- Suzuki, A. (2008) Animating The Chaos, Southern Illionois Press ¹

The animation is beautiful, and with instrumental soundtracks. It’s auteuristic, instantly recognisable, and immersively lovely. Lauded as the Japanese Disney, Miyazaki gives us magical fairytales with more substance than how important it is to marry someone rich and royal. They strike the right balance between whimsy and sentiment, having an ethical message and not preaching to us; being innocent but not patronising.

All this, and against a watercolour world; what more could we want?

Frances Taylor

Frances likes words and pictures, regardless of media. She finds great comfort and escape in film, and is attracted to anything character-driven with a strong story. Through these stories, she will find meaning in the world. Three movies that Frances thinks are really good for this are You and Me and Everyone We Know (Miranda July), I’m A Cyborg, But That’s OK (Chan-Wook Park), and How I Ended This Summer (Alexei Popogrebsky).

When Frances grows up, she would like to write words and make pictures and have cool people recognise her on the street and tell her that they really enjoy her work.

She can be found overreacting and over-caffeinated on Twitter @penny_face, a childhood moniker from her grandmother owing to her gloriously round face.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA