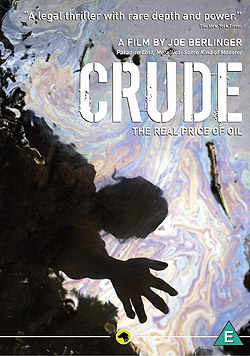

Crude

CRUDE (DVD)

Dogwoof Digital

Release date: April 10th 2010

Certificate: E

Running time: 105 minutes

Director: Joe Berlinger

When I first heard about the documentary film Crude, it sounded somewhat like a cross between two other docs that I had seen. First was Denise Zmekhol’s Children of the Amazon a deeply personal film which centred on the impact the encroachment of the modern world has on the inhabitants of the rain-forest.

The other was the excellent, compelling and infuriating Mugabe and the White African, directed by Lucy Bailey and Andrew Thompson, which followed one family’s protracted and dangerous legal battle against state-sanctioned terror in Zimbabwe. Put these together, environmental issues and a lengthy and difficult legal battle, and you have the basic premise of Crude.

In 1964, Texaco arrived in Ecuador and began scouring the northeast of the country for oil. In 1972 they went into full production in the Lago Agrio oil field in an area solely inhabited by indigenous people. During the oil process there is a bi-product called ‘produced water’ which Texaco sluiced off into large ponds in the areas surrounding their plants. When Texaco left Ecuador, handing over full responsibility for the plants to PetroEcuador, they were charged with repairing any damage done by these ponds and with removing all of the ‘produced water’ and oil.

Since 1993, lawyers acting for the indigenous people of this area have been attempting to bring a class-action lawsuit against Texaco (and subsequently Chevron with whom they merged) and after 9 years of trying the United States, the case was opened in Ecuador.

Crude follows the campaign of the litigators working on behalf of the people of Ecuador throughout 2006-2007 as they attempt, against all odds to win their battle against the massive oil company. Throughout this time we see the devastation that Texaco are purported to have reaped in the area. We see earth dug out the ground black and dripping with oil, we see a dead bird being pulled from the blackened water, and most importantly we meet numerous families who have lost loved ones or in one case a mother and daughter who have both contracted cancer after the drinking of contaminated water.

Texaco’s lawyers and scientists would argue that this is a case of post hoc ergo propter a hoc i.e. that people are assuming that drinking the oily water is the cause of the problems. Their scientists claim that the petroleum levels in the area are not higher than is safe, their legal team claim that the litigators are out for money not for the truth.

There are a couple of reasons that I think that Crude is essential viewing. Firstly, the issue absolutely deserves to be given as much of a voice as possible. Since the film, which ends with a prediction that the trial will go on for another decade at least, there has been a ruling which has stated Chevron must pay reparations which they refuse to do and the Ecuadorian courts have no recourse to force them.

They have also, since the film, attempted to have all of director Joe Berlinger’s footage (over 600 hours) seized and a federal judge has sided with Chevron although Berlinger’s lawyers have appealed.

The other thing that makes Crude even more compelling viewing is the near perfect balancing act. The film is obviously very difficult and enraging. There is not a lot of light in a story full of so much black oil – the legal representatives of Chevron are massively infuriating in their stark denial of any wrong-doing.

It is unsurprisingly heavy-going in places and there are not really two sides of the story to put forward any more than they do. What lifts the film above something like last year’s Countdown to Zero (which is also important viewing but offers no respite from the doomsday angle) are the litigators for the indigenous people; the American lawyer Steve Donzinger, and the heroic Ecuadorian lawyer Pablo Fajardo.

The film shows us people vs the machine in the case of the the plaintiffs and the company and we meet a number of the villagers – the majority of whom have suffered tragedy which they believe to be down to Texaco. What Donzinger and Fajardo bring to this, and what Berlinger cultivates, are moments of camaraderie, of comedy, of sadness, and of hope. When we hear about the death of Fajardo’s brother and the confirmation that it was supposed to have been him, it strikes a terrible, distressing note. When he first sees his picture in Vanity Fair, you cannot help but beam and similarly, the smile on his face when he visits New York and meets Sting also warms your heart despite the fact you’re not hopeful it will ultimately help force the solution you want.

The drama is gripping, the characters are engaging, the story is moving and infuriating. It is heavy, and at times difficult to watch, but it is also a wonderful look at a real David and Goliath story, and a real-life legal thriller.

Ben Nicholson

Ben has had a keen love of moving images since his childhood but after leaving school he fell truly in love with films. His passion manifests itself in his consumption of movies (watching films from all around the globe and from any period of the medium’s history with equal gusto), the enjoyment he derives from reading, talking and writing about cinema and being behind the camera himself having completed his first co-directed short film in mid-2011.

His favourite films include things as diverse as The Third Man, In The Mood For Love, Badlands, 3 Iron, Casablanca, Ran and Grizzly Man to name but a few.

Ben has his own film site, ACHILLES AND THE TORTOISE, and you can follow him on Twitter @BRNicholson.

© 2012 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA

Please wait...

Please wait...