The Master

THE MASTER

The Weinstein Company

Release date: March 11th, 2013

Certificate (UK): 15

Running time: 143 minutes

Writer and director: Paul Thomas Anderson

Composer: Jonny Greenwood

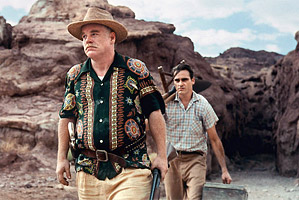

Cast: Philip Seymour Hoffman, Joaquin Phoenix, Amy Adams

There are few films that are masterpieces regardless of their dialogues; images, sounds, light and the composition of minute observations alone become a tour de force which can be both exhilarating and utterly draining. It very much depends on the state of mind of the beholder when she or he goes into the story.

I had been pretty much on edge already when I saw The Master and perhaps not exactly prepared to face the onslaught of a cinema-etude lasting some 140 minutes. I suppose writer-director Paul Thomas Anderson, more or less oblivious to cinematic conventions, could well make a film where the visual experience dominates everything. The Master potentially is such a film but it turns into a rather sublime confluence of images and dialogues — with a story that reminded me of a disastrous friendship in my own past and the mixed feelings of despair and riddance when it was finally over.

Apparently the drama of friendship is very much the point here and in a way, Joaquin Phoenix and Philip Seymour Hoffman play two sides of the same character, being each other’s Alter Ego, fighting and loving one another while letting the walls between them grow higher and heavier. It is the story of unequal drifters who are cut from the same cloth but have had very different lives  and been dealing with their realities in very different ways.

and been dealing with their realities in very different ways.

Freddie Quell (Phoenix) is a master at mixing potentially fatal but pretty effective cocktails from all sorts of chemicals and alcohol. Lancaster Dodd (Hoffman) does — almost — the same with ideas and words. Freddie is a damaged and traumatized war veteran on a prowl for something. Dodd seems to have found it already — he is the charismatic mastermind of The Cause, a spiritual “community” in America’s 1950’s that promises liberation from negative emotions and destructive, all-too-human urges.

Despite the translucence of L. Ron Hubbard, his Dianetics and early Scientology, it could have been any of the quasi-religious movements that often mushroom after wars and other dramatic upheavals. There’s no lack of lost souls seeking the purpose of their survival, looking for new beginnings and longing for a reality other or greater than their own.

Freddie, being a lost soul himself, joins The Cause — although it’s actually Lancaster Dodd he joins. Dodd adopts the younger man the moment he meets him but not without “processing” his personality first. The painful interrogation reveals Freddie’s  sincerity and Dodd’s hypnotic power of manipulation. This is the moment the two men “find” each other but their relationship quickly develops an abysmal drift.

sincerity and Dodd’s hypnotic power of manipulation. This is the moment the two men “find” each other but their relationship quickly develops an abysmal drift.

Freddie becomes Dodd’s guinea pig, bodyguard and muscle in one while the master nurtures his protégé and uses him as a mirror for his overwhelming ego-persona. Anderson unfolds a kind of character choreography that more often than not seems like applied Freudian psychology or Nietzschean philosophy — or something in-between. Phoenix and Hoffman play out a surreal-real duel between their characters — and between themselves it seems. There are moments when their skill is a nudge short of carrying them over the top.

Yet Anderson’s mise-en-scène is realistic as can be — an exact if not pedantic image of America’s post-war decade. The setting keeps the story down-to-earth without turning it into a period drama. On this stage, each event has a meaning however,  Anderson seemingly refuses to hand out a message — he dares us to experience the story without a silent narrator taking sides for us or doing the “explaining”.

Anderson seemingly refuses to hand out a message — he dares us to experience the story without a silent narrator taking sides for us or doing the “explaining”.

When Freddie tries to rid himself of his demons with a rather tormenting procedure, it might be a trenchant comment on the latent absurdity of any kind of “cause” but in the end no one can claim to have understood consciousness or the soul — or what it really takes to make sense of life as it is.

In this light, Dodd’s philosophy more often than not seems arbitrary, “made up” as his own son tries to tell Freddie at one point, and so do his therapies. Whether or not you can heal ills with hypnosis and harsh interrogations that reveal one’s past lives and troubles, is maybe not the question.

Freddie’s psyche more and more appears deeper and richer than Dodd’s and when I finally stopped trying to “get it”, the story felt like Anderson has created an oxymoron of sorts. If a “cause” has a “master”, then the cause may not be really a cause, and the master not a master but once we have associated a larger-than-life character like Lancaster Dodd with larger-than-life attributes, any kind of self-made spirituality creates patterns of superiority and inferiority.

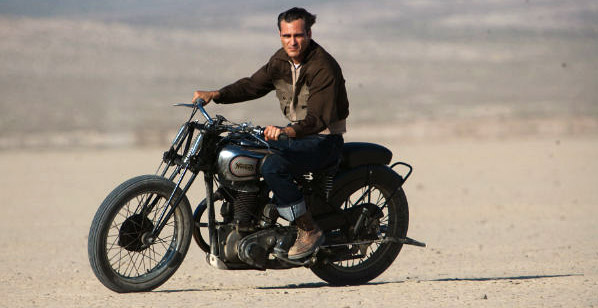

Eventually, Freddie’s inner world turns out to be superior in its own right and he seems to outgrow Dodd and his Cause. Somehow he has always lived a “philosophy” the Master has acquired merely with his head. Freddie radiates a natural but complicated wisdom, even if it verges on destruction. When he brutally lets loose on a  critic of The Cause, it is not quite clear who or what he defends, and the way his imagination and lucidity take turns makes him seem out-of-this-world more than once.

critic of The Cause, it is not quite clear who or what he defends, and the way his imagination and lucidity take turns makes him seem out-of-this-world more than once.

Freddie is looking for something neither Dodd nor The Cause can give him but what he seeks might only be a mirage. We get a sense of this when he tries to recapture a pre-war love affair through flashbacks and wild fantasies in the present. At one of the congregations of The Cause, Freddie imagines all the women being naked. This is just one of the moments where we actually see through his mind’s eye which is rather disturbing.

There is a subliminal uneasiness threading through the entire film. It looks back at a past era but Anderson actually puts up a mirror that reflects the present rather immediately. Again, we may not really understand our world and ourselves, life has become inscrutable. There are new masters who we sort of summoned but distrust deeply.

Through the story of a deep and deeply dysfunctional friendship, Anderson tells of the longing for meaning and true companionship. The Master is not an easy film; it is emotionally challenging and deeply evocative, and it is very long. Storytellers like Anderson don’t seem to care much about time but in the end it’s worth going along for the ride.

Jonahh Oestreich

One of the Editors in Chief and our webmaster, Jonahh has been working in the media industry for over 20 years, mainly in television, design and art. As a boy, he made his first short film with an 8mm camera and the help of his father. His obsession with (moving) images and stories hasn’t faded since.

You can follow Jonahh on Twitter @Jonahh_O.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA