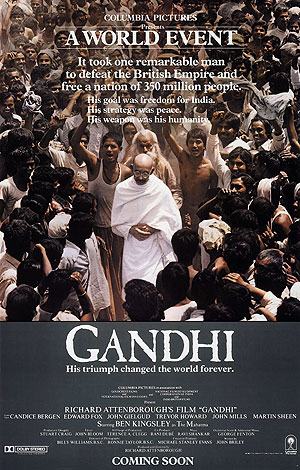

Gandhi

Columbia Pictures

Original release: November 30th 1982

Running time: 187 minutes

Director: Richard Attenborough

Writer: John Briley

Composer: Ravi Shankar, George Fenton

Cast: Ben Kingsley, Rohini Hattangadi, Ian Charleson, Edward Fox, Candice Bergen, Sir John Mills, Sir John Gielgud, Geraldine James

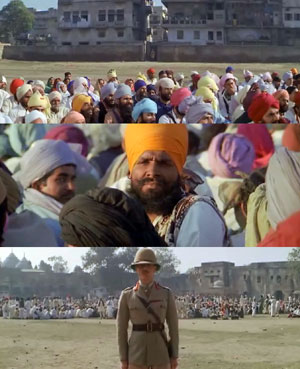

The Jallianwala Bagh Massacre: 01:23:38 to 01:25:43

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

In a world ripe with injustice, suffering, hunger, violence, ignorance and indifference, they often say one man alone can’t make a difference, but this isn’t always true. It depends on what that man is willing to sacrifice in order to bring about change. In the case of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, one man can really make a difference. His story is one that’s now surrounded by legend and folklore. As a result of this it’s sometimes difficult to gain a clear picture of who this saintly figure was that helped to liberate India from the British Empire without having to resort to violence, despite the fierce opposition he faced.

Born in 1869 in Porbandar, a coastal town which was then part of the Bombay Presidency, British India, Gandhi wasn’t an extraordinary child, nor was he a particularly gifted student. By all accounts from his school reports, he was but mediocre. At the age of 13 he was married to Kasturbai Makhanji who was one year old than him. At the age of 15 the couple had their first child, and submitting to his parents’ wishes for him to become a barrister, Gandhi went on to pass the matriculation exam at Samaldas College in Bhavnagar, Gujarat.

In 1888 he left India and attended University College London where he studied Indian law and jurisprudence and trained as a barrister at the Inner Temple. During his time in England he adopted many English customs, including dancing, but practiced abstinence from meat and alcohol as well as of promiscuity having made a vow to his mother in the presence of a Jain monk before he left India. He also became interested in religious thought when he met the members of the Theosophical Society, they encouraged him to the Bhagavad Gita both in translation as well as in the original. After being called to the bar in 1891, Gandhi tried to establish his own law firm in Bombay, but found this venture fruitless due to his shyness and inability to speak up. A couple of years later, he was offered a year-long contract from Dada Abdulla & Co., an Indian firm, on a post in the Colony of Natal, South Africa, then part of the British Empire.

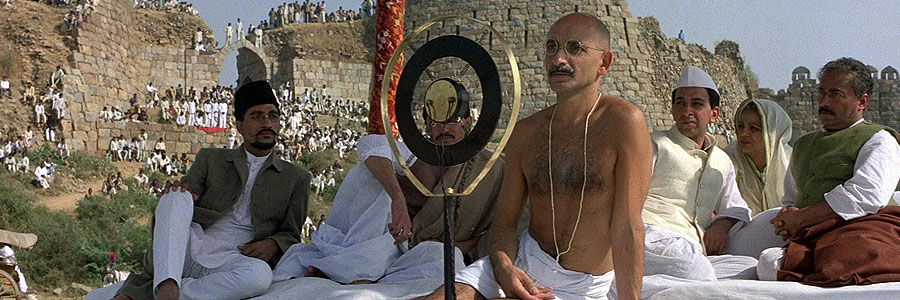

This is where Richard Attenborough’s 1982 bio-graphical film starring Ben Kingsley, dramatizing Gandhi’s life, begins. Whilst travelling first class on a South African train in a whites-only compartment he’s asked for his papers. The shy young man tries to protest that he has every right to be on the train, but the brutish ticket inspector wastes no time in throwing him off. It’s in this moment the 24-year-old realizes the laws are biased against Indians and with the support of his wife and a few friends and officials, he begins a non-violent protest campaign for the rights of all Indians in South Africa. We see the softly spoken Gandhi enduring beatings and arrests and after receiving international attention, the government finally relents their unjust laws by recognising some rights for Indians.

It’s around this time he meets English clergyman Reverend Charles Freer Andrews (Ian Charleson) and the pair strike up a friendship based on mutual respect and admiration for each other, as well as their stance on violence as a means to an end. Following the victory in South Africa, Gandhi returns to India where’s he’s welcomed as a national hero and urged to help them fight for independence from the British Empire. So begins a non-violent non-co-operation campaign on an unprecedented scale with millions of Indians nationwide taking part.

Gandhi, as a film, is truly a cinematic event of epic proportions and what Attenborough has achieved with it is something that has a strong emotional core while at the same telling the life story of a remarkable individual who inspired millions in his home country into action. Kingsley portrays Gujarati lawyer with such a likeness that the image we have of Gandhi in our minds now is actually of the actor playing him. As for the film’s supporting cast, Charleson lends a lot of charisma and charm to the role of Reverend Andrews and his screen-time with Kingsley show how important this friendship was in the efforts to liberate India.

While Gandhi goes on to show us the triumphs of non-violent protests with the Salt March and the setbacks such as the rising tensions between Hindus and Muslims and the Partition of India, of which Gandhi was deeply opposed to, his peaceful means to bring about a unified and independent country would eventually result in his assassination. On January 30th, 1948, while out walking amongst the crowds to address a prayer meeting, Gandhi was shot at point blank range in the chest by Nathuram Godse, a Hindu nationalist who held him responsible for the Partition of India and who opposed the doctrine of nonviolence.

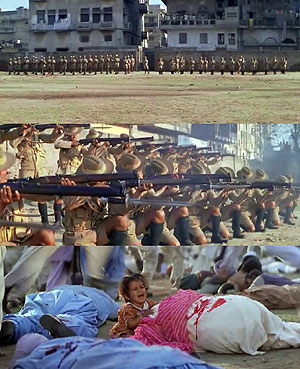

However, this isn’t the most shocking part as we experience Gandhi’s life on screen. The Jallianwala Bagh massacre, spearheaded by Brigadier General Reginald Dyer (Edward Fox), is also depicted in the film. On April 13th, 1919 where some 10,000 or more unarmed men, women and children gathered in Amritsar’s Jallianwala Bagh to attend a protest meeting, despite a ban on this gatherings,

Though the film depicts the massacre and Gandhi’s response to it as he visits the site, we don’t learn very much about what happened to General Dyer and we only glimpse him for a moment afterwards at a hearing where he’s questioned on his tactics. Though official numbers place the death toll at around 400 with 1,000 injured, public enquiry estimates from Government Civil Servants in the city place the number of those killed at over 1,000. Added to this was the fact that the injured could not be attended to because of the curfews enforced at the time. They were left there to die. For his role in this massacre, General Dyer was told to resign his post and upon his return to England he was presented with a purse of £26,000 from a collection set up on his behalf by the Morning Post and writer Rudyard Kipling, who wrote The Jungle Book, demonstrating their support for his actions and “the man who saved India”.

- [1] Kenneth Pletcher, The History of India (2010), The Rosen Publishing Group

- [2] Charles F. Andrews, Mahatma Gandhi: His Life and Ideas (2005), Jaico Publishing House

Although Gandhi can be forgiven for skipping over England’s hero’s welcome to General Dyer after the massacre in favour of busying itself with the task of recounting the landmark moments in Gandhi’s life, Attenborough eschews certain points to paint a picture of a man always opposed violence, even if this isn’t true. We know this because in Reverend Andrews’ Mahatma Gandhi’s Ideas he recalls his disagreement with Gandhi in 1918 when he was encouraging recruitment of combatants for World War I.

Even today we find it hard to reconcile Gandhi’s support for fighting in war with his views on ahimsa, especially when he was the same man who said “Anger is the enemy of non-violence and pride is a monster that swallows it up.” Still, Gandhi is a legend and a hero Gandhi is a film which supports this with a beautifully story and a performance by an actor who’s now become very much part of that folklore.

Patrick Samuel

The founder of Static Mass Emporium and one of its Editors in Chief is an emerging artist with a philosophy degree, working primarily with pastels and graphite pencils, but he also enjoys experimenting with water colours, acrylics, glass and oil paints.

Being on the autistic spectrum with Asperger’s Syndrome, he is stimulated by bold, contrasting colours, intricate details, multiple textures, and varying shades of light and dark. Patrick's work extends to sound and video, and when not drawing or painting, he can be found working on projects he shares online with his followers.

Patrick returned to drawing and painting after a prolonged break in December 2016 as part of his daily art therapy, and is now making the transition to being a full-time artist. As a spokesperson for autism awareness, he also gives talks and presentations on the benefits of creative therapy.

Static Mass is where he lives his passion for film and writing about it. A fan of film classics, documentaries and science fiction, Patrick prefers films with an impeccable way of storytelling that reflect on the human condition.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA