The Incredible Shrinking Man

THE INCREDIBLE SHRINKING MAN (MOVIE)

Universal Studios

Original airdate: February 22nd, 1957

Running time: 81 minutes

Director: Jack Arnold

Writers: Richard Matheson,

Cast: Grant Williams, Randy Stuart, April Kent, Paul Langton, Billy Curtis

The entire genre of 1950s science fiction B-movies is backlit by the flash of the atomic bomb. In these films the implications of this new nuclear reality are either dealt with head-on in classics like The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951) or contained implicitly, haunting the shadows in menacing, ill-defined form – literally so in The Blob (1958). While alien visitation, both violent and benign, was the most recognizable trope from the period, another came in the shape of the monstrous mutation. In American films like Tarantula (1955) and The Amazing Colossal Man (1957) – not to mention the legendary Godzilla, which first appeared in Japanese cinemas in 1954 – aberrations of nature towered like mushroom clouds over the landscape. The symbolism was clear; Prometheus had stolen fire from the gods and now those gods were going to stomp all over his puny creations, munching their way through handfuls of fleeing masses as they went.

But if the terrifying new power of the Bomb found apt, and often comic, representation in these monsters, they also embodied a more diffuse metaphor for a feeling of disorientation in terms of scale, a kind of cultural vertigo. The Bomb had shown how the manipulation of the infinitesimally small could transform mankind into ‘the destroyer of worlds’, to use J. Robert Oppenheimer’s famous phrase, and such paradoxes of the micro- and macrocosmic were proliferating with each new scientific discovery. Giant telescopes reached ever further into space, revealing the universe as incomprehensibly more vast than had previously been supposed, while quantum physicists had discovered that the elemental stuff it was made from contained its own bizarre worlds-within-worlds, buzzing with electrons, protons, neutrinos and who knew what else.

‘My original story was a metaphor for how man’s place in the world was diminishing,’ said Richard Matheson of his novel, which he himself adapted for Jack Arnold’s film version of The Incredible Shrinking Man (1957). As its title makes blatantly clear, it distinguished itself from contemporary SF movies by flipping the concept of the radioactive mutation on its head. This is not all that differentiates it either. The wholly domestic setting in which the action takes place makes it difficult to classify as a science fiction movie at all, and prefigures the New Wave SF of the 1960s where the emphasis moved away from space opera sensationalism to a more subtle examination of the psychological effects created by new technological innovations – an exploration of inner as opposed to outer space.

The radioactive fog which envelopes the hero Scott Carey (Grant Williams) at the beginning of the film is the catalyst for his transformation, which begins six months later  when he’s standing in front of the mirror at home, puzzled by the fact that his clothes no longer fit properly. The environment is suburban, middle-class and conventional, with Carey’s wife, Louise (Randy Stuart), fulfilling her allotted role as homemaker, the home itself exhibiting a rich bounty of the latest consumer modcons. The first half of the film focuses on Carey trying to cope with his bizarre predicament as lab-coated doctors, with the help of a ubiquitous Geiger counter, establish that he is indeed shrinking.

when he’s standing in front of the mirror at home, puzzled by the fact that his clothes no longer fit properly. The environment is suburban, middle-class and conventional, with Carey’s wife, Louise (Randy Stuart), fulfilling her allotted role as homemaker, the home itself exhibiting a rich bounty of the latest consumer modcons. The first half of the film focuses on Carey trying to cope with his bizarre predicament as lab-coated doctors, with the help of a ubiquitous Geiger counter, establish that he is indeed shrinking.

Because of his size, Carey loses his job. Then his brother runs out of funds to support him and suggests he sell his ‘incredible’ story to the newspapers. Impotent and humiliated, the toddler-sized Carey rows with his giant wife. Their bickering leaves the viewer in an uncomfortable double-bind. On the one hand there’s the desire to laugh at the absurdity of it all – the concept of the shrinking or small human is generally played for laughs in the cinema, after all – but this desire is kept in check by the genuine distress and desperation of the couple, who act out these domestic conflicts like a Douglas Sirk melodrama. Such cognitive dissonance emphasizes the increasingly surreal and disturbing nature of Carey’s position, culminating in a sequence that sees him wandering through the sideshows of a circus that has rolled into town. It’s only here among the marginalized freaks that he finds some respite and once again begins to feel part of a community.

Despite this brief hiatus, Carey is soon shrinking again. Now he lives in a doll’s house at the bottom of the stairs – a world within a world – stomping backwards and forwards in a frenzy,  berating his wife in barely audible, squeaky tones. “Every day it was worse,” he says on the voice-over. “Every day I was a little smaller, and every day I became more tyrannical in my domination of Louise.” Tyrannical is a canny choice of words given dictators’ penchant for gigantism in the Twentieth century, the Great Leader captured in heroic profile on 100ft banners or cast in towering bronze statues, both standard products from the totalitarian tool-kit.

berating his wife in barely audible, squeaky tones. “Every day it was worse,” he says on the voice-over. “Every day I was a little smaller, and every day I became more tyrannical in my domination of Louise.” Tyrannical is a canny choice of words given dictators’ penchant for gigantism in the Twentieth century, the Great Leader captured in heroic profile on 100ft banners or cast in towering bronze statues, both standard products from the totalitarian tool-kit.

But what these scenes emphasize most explicitly is Carey’s sense of emasculation. At the start of the 1950s, the French feminist writer Simone de Beauvoir had already been published in America, and gender issues were slowly pushing their way into the political mainstream, certainly in the West. At the same time manual labour was increasingly becoming the work of machines rather than men, further engendering an anxiety of obsolescence in the male psyche. Issues of gender would join those of race and ethnicity when full-blown identity politics took centre stage the following decade, but given the suffocating conformism of the 1950s, it was in B-movies like The Incredible Shrinking Man – along with the wonderful low-budget Attack of the 50ft Woman (1958) – where such shifts in gender relations could be examined with any acuity. Martin Scorsese refers to the directors of such films as ‘smugglers’. In his documentary A Personal Journey Through American Movies (1995) he says, ‘The world of B films was often freer and more conducive to experimenting and innovating. They allowed for the expression of different sensibilities, offbeat themes or even radical political views, particularly when the financial stakes were minimal. Less money, more freedom.’

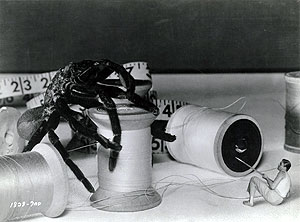

When the house cat chases Carey from his doll’s house and leaves him trapped in the basement, the film changes in tone and takes on a more fantastical dimension, especially given our hero is now barely an inch in height. The vertiginous stairs offer no route of escape, and so he’s left to  defend himself without his wife for protection – especially now she assumes the cat has eaten him. In dystopian language, Carey describes how ‘The cellar floor stretched like some vast primeval plain, empty of life, littered with the relics of a vanished race.’ But in spite of the terrors of his new existence – not least the giant spider that shares this subterranean world – Carey’s fight to survive has the effect of reaffirming his masculine identity, bringing out a rugged, Thoreau-like individualism and resourcefulness. Here, as with all hero narratives, disaster provides the opportunity for self-transformation.

defend himself without his wife for protection – especially now she assumes the cat has eaten him. In dystopian language, Carey describes how ‘The cellar floor stretched like some vast primeval plain, empty of life, littered with the relics of a vanished race.’ But in spite of the terrors of his new existence – not least the giant spider that shares this subterranean world – Carey’s fight to survive has the effect of reaffirming his masculine identity, bringing out a rugged, Thoreau-like individualism and resourcefulness. Here, as with all hero narratives, disaster provides the opportunity for self-transformation.

This capacity to revel in the absurd, fragmented and hallucinogenic states of modernity had a particular appeal for the cult writer JG Ballard, who regarded the film as a masterpiece of imaginative cinema. ‘It poses basic metaphysical questions about the nature of existence – finding yourself a strange human being,’ he said. ‘These fears lurk in the back of everybody’s consciousness, and make us realize that consciousness is a very special condition – there’s nothing normal about normality. It tapped into those things much more deeply than some “serious” movie.’

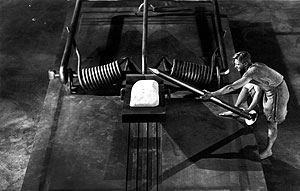

After Carey has defeated the spider, impaling it on a pin that doubles as a sword, the shrinking process continues, and he is now small enough to make it through the ventilation grate that leads from the basement to the garden. Emerging into this vast jungle, he looks up at the night sky  glittering with stars, and ponders how ‘The unbelievably small and the unbelievably vast eventually meet, like the closing of a gigantic circle.’ His monologue builds to a state of euphoria, an existential epiphany as the camera zooms out from the garden and zooms in towards the stars, picking out cluster and spiral galaxies as the music reaches its Wagnerian crescendo. ‘All this vast majesty of creation – it had to mean something. And then I meant something too. Yes, smaller than the smallest, I meant something too! To God there is no zero. I still exist!’

glittering with stars, and ponders how ‘The unbelievably small and the unbelievably vast eventually meet, like the closing of a gigantic circle.’ His monologue builds to a state of euphoria, an existential epiphany as the camera zooms out from the garden and zooms in towards the stars, picking out cluster and spiral galaxies as the music reaches its Wagnerian crescendo. ‘All this vast majesty of creation – it had to mean something. And then I meant something too. Yes, smaller than the smallest, I meant something too! To God there is no zero. I still exist!’

If it all seems a tad overblown in these jaded times, it nevertheless remains an extraordinary end to a Hollywood film from that era, or any era for that matter. Equilibrium is not re-established. No cure is found to return our hero to his regular size, reunite him with his mourning wife and thus resume suburban normalcy. Instead that life is left behind in an ecstatic and mystical vision, a sense of wonder at the novelty and strangeness of this new atomic epoch. And if it was an epoch that had unleashed monsters, both real and imaginary, the film’s conclusion works to remind us that these monsters are of our own making, and what’s more, we still have the power to defeat them.

Robert Bright

Robert Bright has been working as a journalist since the early 1990s, and such is his vintage, he remembers seeing Goodfellas at the cinema, a film that remains one of his favourites, and its director Martin Scorsese one of his heroes.

He is interested in film noir – particularly such classics as The Maltese Falcon and Out Of The Past – and American science-fiction B-movies of the 1950s, like Howard Hawks’s The Thing. Other favourites, taken at random, include Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad And The Beautiful, John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

You can follow him on Twitter at @MKUltraBright.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA