A Clockwork Orange

Polygram

Original release: January 13th, 1972

Running time: 131 minutes

Writer and director: Stanley Kubrick

Composer: Wendy Carlos

Cast: Malcolm McDowall, Patrick Magee

Opening scene 00:00:00 to 00:02:17

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

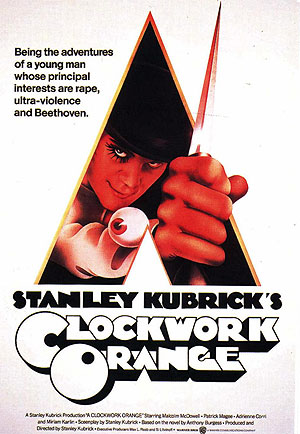

With an unflinching mix of sex, brutal and stylised violence, themes of government mind control, and a charismatic anti-hero lead character, Stanley Kubrick’s A Clockwork Orange has long been a magnet for commendation, criticism and controversy.

In the UK, the film was slated by elements of the press and government, who linked it to real life juvenile violence¹. In addition, Kubrick himself started receiving death threats, leading to his decision to ban Brits from watching it, a move that forced it underground and massively boosted its reputation as a dangerous work of art.

The story, closely following the Anthony Burgess novella on which it’s based, centres on Alex (Malcolm McDowell), a young thug who spends his days skipping school and his nights prowling the streets, leading a gang of friends, known as “Droogs” on drug fuelled rampages of robbery and rape. When one such episode ends in murder, Alex is hauled off to prison, where he ends up being part of a scientific experiment to use brainwashing techniques to cure people of their evil impulses – but does robbing Alex of the ability to do evil make him a truly good person?

Much of the tone and content is foreshadowed in the brilliantly crafted opening scene, which is an abject lesson is using only a few elements to deliver a great deal of information, and it’s worth examining each of these elements individually to see how they work together.

The first thing we see is a completely red screen, and a particularly lurid red screen at that. This foreshadows the blood that is set to flow throughout the film, as well as being a colour associated with lust, establishing the link between sex and violence that Alex will show later.

The first thing we hear is Wendy Carlos’ synthesiser rendition of the March For The Funeral Of Queen Mary by Henry Purcell. The piece is transformed from a stately, respectful, dignified funeral dirge, into a hellishly cold, ominous piece of music, with metallic percussion, and dissonant undertones.

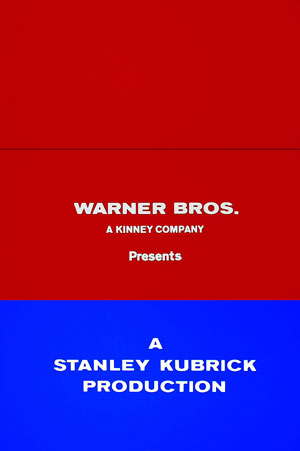

Next, we see three very sparse title cards, “Warner Bros presents”, “A Stanley Kubrick Production”, and “A Clockwork Orange”, and it’s worth noting two things. Absolutely no other names are mentioned other than Kubrick’s, meaning that he wishes us to see the film as very much as his brainchild; also the card with his name appears on a blue background, perhaps using the contrast of a cooler colour to imply a certain amount of detachment and non-endorsement on his part of the actions of Alex.

The next substantial image we see is a close up of the face of Alex, wearing a faintly unnerving grin and a malevolent twinkle in his eye. In a wonderfully subtle touch, he’s visibly breathing quite heavily, almost like a predator about to pounce on its prey. Without a word of dialogue, we’ve already established some of the basics of the main character and the tone of what we’re about to see, the portentous atmosphere enhanced by the music.

Then the camera starts to pull back to gradually reveal the other Droogs and the bizarre décor and other occupants of the Korova milk bar. The facial expressions and body language of the other three Droogs are either imbecilic or passive, and it’s obvious from that Alex is the leader of the pack.

The final ingredient is a short piece of voiceover:

This dialogue all appears in the book but here it’s pared down from three pages to one paragraph, which is all that’s needed in this context, as the other elements fill in the rest of the descriptive gaps for the viewer. The voice-over is still an important part of the opening however, and serves two main purposes; firstly it establishes the “Nadsat” language used by the Droogs, and, as that is such an intrinsic part of the speech of the  main characters, it’s important to get the audience acquainted with it as early as possible. Although it might arguably be a bit of a gamble, thanks to the context provided by the other elements, it’s surprisingly easy for a first-timer to pick up what the words mean.

main characters, it’s important to get the audience acquainted with it as early as possible. Although it might arguably be a bit of a gamble, thanks to the context provided by the other elements, it’s surprisingly easy for a first-timer to pick up what the words mean.

Secondly, it’s delivered in a tone of voice that’s charming and hugely self-assured, but also slightly mocking, playful, and sinister, so we establish that side of the character of Alex, and also that he and his gang like drugs and violence, and that both things are regular features of their lives.

With one unedited pull-back shot, minimal but effective acting, a few sentences of voice-over, some great production design, and a cold, creepy soundtrack, we’re quickly initiated into the look, themes and content of the rest of the film, and all in a little over 2 minutes.

However, one good scene, or even several, doesn’t a cinematic masterpiece make, and A Clockwork Orange is hampered by some real problems with pacing, which drags the film down and makes long periods, especially in the second half, feel interminable.

The first twenty minutes are a breath-taking outré ride, propelled not just by the violence, but also by the magnetic lead character and wonderful dialogue, two things that we’re introduced to in the opening scene. As the elaborate vocabulary of Nadsat is unveiled to us, the baroque language, combined with a self-assured swagger, make Alex feel like an ersatz Shakespearean character, a mix of the sinister charm of Richard III and the energy and lustful appetite of Falstaff. The Droogs rampage is repulsive and disturbing, but it’s also driven by an almost primal energy. For them, violence is like sex and drugs, an exhilarating sensual pleasure, and as a viewer, it’s, at times, almost impossible not to be caught up in this feeling.

However, this vitality is soon dissipated by a script that’s relentlessly talky, particularly in the second hour, which seems to go on for a lot longer than that. When combined with cringe worthy comic interludes that look like they would be more at home in a Confessions of… film or Benny Hill sketch, and some grating and unrestrained performances, in particular Patrick Magee, who sometimes sounds like  he’s doing a bad impression of Boris Karloff, the good work of the opening’s nearly undone.

he’s doing a bad impression of Boris Karloff, the good work of the opening’s nearly undone.

There’s also something unsavoury about Kubrick’s decision to portray Alex as more deserving of sympathy than his victims. Admittedly, the lead character in A Clockwork Orange is not a hero, or even a lowly downtrodden “Everyman”, in the style of Winston Smith or Joseph K type. He is a sadistic, unrepentant criminal, and Kubrick himself said,

A fascinating challenge as to how far people are prepared to take their principles, but there’s little in the way of compassion for any of Alex’s victims. The rape scene is particularly difficult to watch. It’s infused with the obvious sense of fun and play that the gang feel, embodied by Alex belting out Singing In The Rain throughout, but it lacks any kind of emotion and empathy for the victims, as though they’re merely facilitators in the far more important story, the journey of Alex.

Despite, at times, the turgid script, and the murky morality, A Clockwork Orange went on to huge commercial and critical success, taking in over $26 million from a $2 million budget, and picking up Oscar nominations and a host of Film Critics’ awards. However, since its release, it seems that what people really to connect with, more than the story, the moral arguments over what makes people truly good or evil, or even the idiosyncratic language, is the film’s music, imagery, and fearsome reputation.

- Censored: The Story of Film Censorship in Britain by Tom D. Mathews ¹

- Kubrick on A Clockwork Orange – An interview with Michel Ciment²

- Strange Fascination: David Bowie – The Definitive Story by David Buckley³

In the early 70s, David Bowie regularly came on stage to Wendy Carlos soundtrack, and dropped Nadsat into the lyrics of the song Suffragette CityClockwork Orange gags. The image and reputation of the film seems now to be used almost as shorthand to signify something decadent, amoral, and dangerous, albeit in an ironic, knowing manner.

I first saw it while in High School, a proud owner of one of the aforementioned grainy bootlegs, and it’s easy to see why A Clockwork Orange still appeals to certain sorts of teenagers. Alex is a nihilistic thug, but he’s also a charismatic figure and much smarter than many of the adults he encounters. He has, like many adolescents, a distinctive dress sense, language and taste in music. Watching the film now with older, more objective eyes reveals many flaws in the overall end product, but I have yet to see a more powerful, alluring and exciting opening two minutes of a film, and a more brilliant lesson in how to use minimum elements to maximum effect.

Simon Powell

Simon grew up on a steady diet of James Bond and Ray Harryhausen films, but has been fascinated with the horror genre since a clandestine viewing of A Nightmare on Elm Street as a teenager. Since then his tastes have expanded to take in classic horror from the Universal and Hammer Studios, as well as branching out into Video Nasties, Sci-Fi, Silent Comedies, Hitchcock and Woody Allen.

Apart from getting married, one of his fondest memories is buying a beer each for both Gunnar “Leatherface” Hansen and Dave “Darth Vader” Prowse at a film festival, and listening to their equally fascinating stories of life at totally different levels of the industry.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA