John Waters,The Filthy Auteur

Like the movies themselves, there are also many perspectives on the authorship of a film. From the initial celebration by scholars who put film alongside important works of literature or music, to the shifts and evolution that gave birth to the development of The Auteur Theory, contemporary cinema has continued to pioneer this tradition to various affect. This result was championing an era where high culture had been replaced by a staple diet of movie consumption, where films of unknown directors were created by new visions and approaches, presenting their views on life through stylistic positions.

Contemporary cinema presents a diverse pool of celluloid offering, and it seems no creative vision remains unbroken.

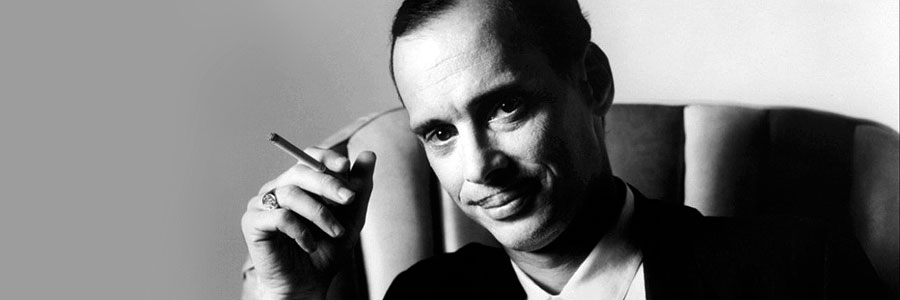

John Waters (2009) by Poppy-de-Villeneuve, Modern Painters

John Waters (2009) by Poppy-de-Villeneuve, Modern PaintersOne such filmmaker, John Waters, has created a body of work that, while being shocking and kitsch has increasingly become more palatable to mainstream audiences. As his body of work is celebrated by audiences, Waters’ aesthetic has been embraced as one of contemporary cinema’s finest auteurs.

Auteur theory had its origins in the work of young French critics writing for French film journal Cahiers Du Cinema. Truffaut’s pivotal article A Certain Tendency In French Cinema (1954) argued that a director-led approach to film created ‘something truly cinematic’ rather than just adding pictures to a script.

They looked beyond post war France to ‘industrial’ Hollywood, studying directors who could “stamp his own identity upon a film despite the commercial pressures within the studio system” (Butler 2006 p.35). Additionally, American critic Andrew Sarris (Notes On The Auteur Theory, 1962) argued that the Hollywood ‘system’ was cinema worthy for the mere fact that there were many talented artists working under it.

He recognised technique, personal style and inner meaning as important, linking them to directors as technician, stylist and auteur. Through this identification of the auteur in the Hollywood cinema, Sarris saw that it had a greater propensity to add cinematic value compared to European cinema. Butler argues that Sarris’ approach fails the critic to recognise that a recurring motif could have been made by any director as opposed to an individual director.

Pink Flamingos (1972), dir. John Waters

Pink Flamingos (1972), dir. John WatersIn Waters’ Pink Flamingos, Polyester and Serial Mom there’s a Nuclear family led by a female figure but the same could be said of Spielberg’s E.T. (1982). Here, there’s difficulty in establishing the director or a recurring pattern. Further investigation is required. Waters can be identified as a director who likes the dysfunctional relationship of a matriarchal family (made complicated by vice, juvenile delinquency, amoral societies and suburban consumerism), quirky dialogue, kooky characters, nostalgic inspired art design of his mise-en-scène and life goes on endings (the not-guilty verdict of Beverly Sutphin in Serial Mom and the dirty little secret it becomes within the family, the violent climax of Polyester and the rise of the trash family in Pink Flamingos).

Furthermore, Levy argues that Waters makes good guys versus the bad guys movies where the bad guys are really the good guys and they always win. The difference lies

In Pink Flamingos, characters have sex on top of chickens and ‘actually fuck them to death’. In Polyester, all of the family members are freaks. They have addictions like teen pregnancy, glue sniffing, and extra-marital affairs, or the fetishisation of foot stomping. The unsettled heroine in Serial Mom isn’t just a devoted batty mother who makes a couple of obscene phone calls, she’s a psychotic killer.

In fact most of Waters’ charming lead characters are inspired from society’s underbelly and low culture, thrown in nostalgic genres (teen, musical and 1950’s melodrama) who subscribe to crass behaviour, becoming vulgar freedom fighter figures in the process. Contemporary cinema has seen a focus on individual figures since the emergence of independent film in the 1980’s. We’ve seen films which express their visions, driven by personal choices, becoming one man publicity machines rather than a hired gun within Hollywood.

Polyester (1981), dir. John Waters

Polyester (1981), dir. John WatersWollen argues that the cult of personality, where certain directors are celebrated can be drawn from early auteur theory.

Furthermore, he disagrees with the Cahiers approach as it grew from individuals and not a codified set of ideas as

Here, directors whose work had no real sense of worth devalued the currency of film. Wollen argues that genuine film analysis lies in the entirety of the director career. It would’ve been difficult to accurately analyse the films of Waters had it not been for his lengthy career. Under Wollen’s model, Waters is an auteur even if he’s made films about menacing fat drag queens or a demented film director, stalking serial killers, drug addicts and sluts that have a home, delinquents that survive the ‘squares’ world or a trash talking film about racism and integration. Wollen (1969) discusses the idea of opposing sets of ideas (antinomies) within the director’s films.

Hairspray (1988), dir. John Waters

Hairspray (1988), dir. John WatersIn Serial Mom, Beverly Sutphin (Kathleen Turner) is the unhinged heroine who’s overly protective of her family and seeks revenge on their critics. This illustrates a relationship between antinomies: civilised vs. savage, moral vs. immoral, family vs. community, hunter vs. hunted, books vs. gun, and sane vs. insane. Under Wollen’s argument, such antinomies can be found in all Waters’ films. Wollen undoubtedly renders the notion of ‘auteur’ as something by which we can look at these sets of opposing ideas but part of this meaning is delegated by those actively reading the film.

While contemporary cinema has continued to celebrate the work of individual directors driven by personal choices to express themselves, Wollen would argue that auteur theory is not be about the ‘cult of personality’ but rather a person who happens to work in the medium of film. John Waters is well known for his self-described ‘bad taste,’ having made films spanning over forty years proving that his audiences have the same tastes too. By using Hollywood genres, he allowed audiences to identify with a nostalgic past but at the same time created work with a depoliticised underbelly because of his camp perspective.

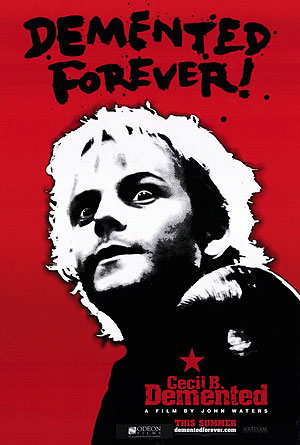

Hairspray deals with black Baltimore and the American civil rights movement, Polyester pits the nuclear family against pornography, drugs, and abortion, Serial Mom highlights the lengths (violence and murder) a mother will go to protect her children, and Cecil B Demented takes an anarchistic approach to corporate Hollywood by way of celebrity, kidnapping and murder.

Cry-Baby (1990), dir. John Waters

Cry-Baby (1990), dir. John WatersHere, Waters deliberate take on stories of family and its support, cohesive society and integration focuses primarily

His films looks at American culture; although they’re non-fictional, they’re nostalgic comedies that mix up genres and use of mise-en-scène to tell their tales and at the same time differentiate between style and trash (Benson-Allott 2009).

Ultimately, his work offers a contemporary critical definition to the nature and practice of the auteur in contemporary cinema and its inherent solipsism. Waters’ political and nostalgic style provides a critical definition of an auteur in contemporary cinema. His films, wrought with camp perspective have been considered by some as the ultimate in auteurism and over time, his films have gone from niche to being embraced by mainstream audiences.

Waters maintains he tries to please an audience that thinks they’ve seen everything,

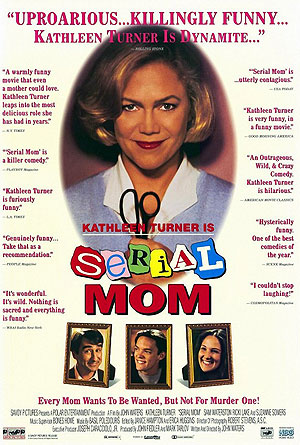

Serial Mom (1994), dir. John Waters

Serial Mom (1994), dir. John WatersIt’s an approach that led him to make Pink Flamingos (competitiveness and war) and Polyester (dysfunctional Nuclear family), both comedies that have no socially redeeming values and that audiences can laugh at- the film or taking aim at American culture (Waters 1981).

Sontag (1999) argues that this moral ambiguity often confuses the ideological intent (society decay and death of the family) of a comedy that uses humour to integrate someone or something into the mainstream (including Waters himself) or both. Others argue that he simply possess an unsparing wit of a satirist. His later films (after Polyester) made money, had increased budgets and involved unions, it’s been argued that

Later films, such as Serial Mom see the cherished cult of the individual and family values go out of the Water’s window and that there appeal to wider audiences indicates the films have

At the same time, other popular shows emerged on television, such as South Park, which popularised bad taste to the point it no longer offended.

Although, much of popular culture is often tamed and domesticated ideas that appeal to mainstream tastes, Waters’ audiences never lose their pungent or tart tastes. Tofts (1998), argues that a revival of Pink Flamingos twenty five years later, illustrates

Cecil B Demented (2000), dir. John Waters

Cecil B Demented (2000), dir. John WatersAn important issue arises in terms of political motivations of post-modern nostalgia films. Pink Flamingos exemplifies the importance of genre with mainstream Hollywood film with its desire to recall the past, and which

Tofts (1998), argues Waters was simply cultivating his art of bad taste,

Waters always regarded The Wizard Of Oz as his favourite film, like many others, who also value friendship and people saving each other. In fact, the lives of many people in contemporary society reads like a Water’s film; plots that expose fraud, exposing the person behind the curtain really has no power (Elders 2011).

Today, his films continue to be embraced by contemporary audiences, re-envisioning the present day relationships between audiences, political ideology and film nostalgia, where you can be transported to another world, learn something new and come back.

Auteur theory suggests the director has the vision. Contemporary cinema no longer follows the same set of ideas and audiences are free to interpret movies at their own will. Although Hollywood makes genre based films which audiences lap up, we live in a Participatory culture, where information is created, consumed and shared by everyone.

This free flow of information has developed the Auteur theory. Increasingly, the director, as a unified source of meaning, now comes to include many other people. Film audiences, through the internet are able to recognise mise-en-scène and also the work by the director of photography, the set and costume design. There’s an increasingly awareness of the position of the writer, producers, and celebrity culture.

Although contemporary audiences may go to see a Julia Roberts’ movie, not knowing who directed it or its influences, they understand the language of film as they’ve grown up on a staple diet of movie watching. They’ve become savvy with sensibilities championed by over a hundred years of film history.

SOURCES:

1. Bulter, A. Film Studies (2005), Kamera Books

2. Levy, A. Still Waters (2008), New York: Volume 41

3. Duralde, A. John Waters: Here To Corrupt You (2006), The Advocate

4. Monaco, J. How to Read a Film (2009), OUP USA

5. Sampey, J. R. John On The Spot (2007), Adweek, Volume 48, Issues 14-26

6. Waters, J Shock Value, (1981), Dell Pub. Co

Kevin McGreal

Kevin McGreal is a playwright and performer based in Melbourne, Australia. He runs his own blog, Scruffystjohn, where he writes about the arts, culture and people. You can also follow him Twitter @kevinmcgreal.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA