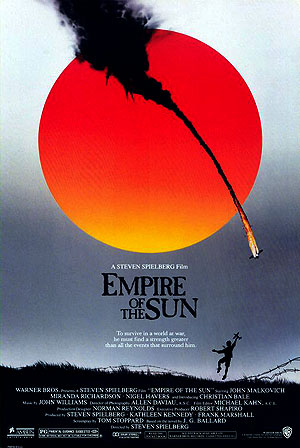

Empire Of The Sun

EMPIRE OF THE SUN (MOVIE)

Warner Bros.

Original release: December 25th, 1987

Running time: 154 minutes

Director: Steven Spielberg

Writers: Tom Stoppard, J. G. Ballard (novel)

Composer: John Williams

Cast: Christian Bale, John Malkovich, Miranda Richardson, Nigel Havers

Empire Of The Sun has been called Steven Spielberg’s ‘death of innocence’ film, but that description doesn’t quite capture the true desolation of what remains the director’s bleakest, most hopeless work.

An adaptation of J.G. Ballard’s same-titled autobiographical novel, the film breaks the rules of biopics and historical epics by shrouding in mystery the very subject it should be illuminating. In doing so, it emerges as a complex and rewarding piece of drama that’s as much about the death of identity as the death of innocence. Beginning with the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in 1941 and concluding with the atomic attack on Nagasaki four years later, Empire Of The Sun focuses on the story of Jamie Graham (Christian Bale), a British boy brought up in China and living in a state of cultural confusion

The opening scene sees him singing Welsh hymn Suo Gân in a Chinese church decorated to resemble a British one, while later he strays from a costume party dressed flamboyantly as Sinbad and stumbles across a battalion of Japanese soldiers. These moments, with their stark visual contrasts and distant framing, serve to isolate Jamie from his surroundings, the audience and his own sense of self. As is typical of his film-making, Spielberg links Jamie’s fractured identity to his lack of a reliable father figure. John Graham (Rupert Frazer) is a negligent parent who seems more concerned with his golf swing than his son.

A rich businessman, he attends the costume party dressed as a pirate but his plunder stands for nothing when he and his wife are separated from Jamie during the occupation of Shanghai. When Jamie returns home hoping to find them, all he discovers in this once opulent abode is scattered talcum powder scarred by clinging finger prints and imposing boots marks – ghostly indicators of the violence that has poisoned his life. Such scenes inspired critic Andrew M. Gordon to refer to Empire Of The Sun as “a child’s dream of war” and this is evident in the writing as much as Spielberg’s imagery. Tom Stoppard’s masterful script is a typically postmodern effort from the author, playing with cinematic form and asking the audience to consider the film as a piece of fiction, born from Jamie’s imagination as much as his reality.

This sense of fantasy comforts the boy and when the film moves to its primary location, the Suzhou Creek Internment Camp, he conjures two flawed father figures to replace the one he’s lost. American ship steward Basie (John Malkovich) is the first and the most post-modern. Almost identical to a character on a comic book Jamie carries with him, Basie is literally a fantasy come to life and his survivalist, something-from-nothing spirit makes him an embodiment of the American Dream and an immediate hero to Jamie. But Basie is a dark twist on American endeavour who reduces life to dollars and cents.

Seeing the boy as an asset, he takes ownership by renaming him Jim (“a new name for a new life”) and tries to trade him to anyone who needs a labourer. “Buying and selling,” he says triumphantly, “you know: life!” British doctor Rawlins (Nigel Havers) is the second father figure. A refined British ideal of heroism, he nurtures Jim by maintaining his education and teaching him moral responsibility. He’s a good man and a better role model than Basie, but like Jim’s father, he’s clueless about the Eastern culture he lives in.

When the camp’s commanding officer, Sgt Nagata (Masatô Ibu), arrives to destroy Rawlins’ hospital in retaliation to American bombing, the doctor fights back, leading to further violence that only ceases when Jim bows to Nagata, showing him the proper cultural respect. The moment muddies Jim’s identity further, with Spielberg  highlighting the positive elements of his cultural confusion. Unlike everyone else, Jim can connect with other nationalities and rejects the good/evil binary that war has forced upon him. He makes friends with a Japanese boy (Takatarô Kataoka) and repeatedly associates Japanese pilots with the sun, a key Spielbergian signifier of truth.

highlighting the positive elements of his cultural confusion. Unlike everyone else, Jim can connect with other nationalities and rejects the good/evil binary that war has forced upon him. He makes friends with a Japanese boy (Takatarô Kataoka) and repeatedly associates Japanese pilots with the sun, a key Spielbergian signifier of truth.

The Japanese are human beings, not ‘the enemy’, and the warmth Jim has towards them suggests he could grow up to become a better man than all the fathers he aspires to, one with more compassion than John and Basie, and more cultural understanding than Rawlins. It’s an identity that’s never allowed to take shape though. War catches up with Jim when American planes bomb Suzhou Creek in one of the film’s defining sequences. Amongst the madness, Spielberg focuses on one pilot as he swoops past. Shot in slow-motion, the pilot waves triumphantly to Jim, forcing him to identify with American heroism again. Unsure of who to idolise, which identity to try to become, Jim finally breaks down and reveals he can no longer remember what his parents look like.

He’s morphed so much, retreated so far into false notions of heroism, nationality and identity, that there is no real, true Jamie Graham any more. This is brought into literal truth in the film’s closing scene, which reunites Jim with his parents in a Shanghai orphanage. A grey-faced Jim stands in the middle of a crowd of children seeming disinterested and hopeless. Spielberg’s camera moves uncertainly across the children and when Jim enters the frame we struggle to recognise him, despite having spent two-and-a-half hours with him. His parents are the same and similarly he fails to acknowledge them.

- Andrew M. Gordon, Empire of Dreams: The Science Fiction and Fantasy Films of Steven Spielberg (Rowman & Littlefield, 2007)

When Mrs Graham finally realises this broken boy is her son, they embrace, but it’s a hardly a happy ending. Jim stares over his mother’s shoulder with glassy eyes that tremble with tears and confusion. Spielberg cuts to a shot of a celebrating Shanghai and then to one of Jim’s suitcase containing all his belongings, floating in a river.

The child Jamie is dead and the adult Jim never got a chance to live. What then will become of the shell that remains?

Paul Bullock

Paul fell in love with cinema when dinosaurs ruled the Earth. A childhood viewing of Jurassic Park introduced him to the power and wonder of the silver screen, and after his dreams of directing were shattered by crumbling papier-mâché sets, disobedient action figure actors and a total lack of talent, he quickly turned to writing, thus proving that life does indeed find a way.

When not citing scripture from the apostle Ian Malcolm, Paul also enjoys the films of Billy Wilder, Paul Thomas Anderson, Stanley Kubrick, Frank Capra, Martin Scorsese and Werner Herzog. His favourite film is The Apartment and his favourite apartments are in films. They're much cleaner than his.

Paul can also be found talking nonsense on Twitter and his website Quiet of the Matinee. He works through his addiction to a certain bearded director on From Director Steven Spielberg.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA