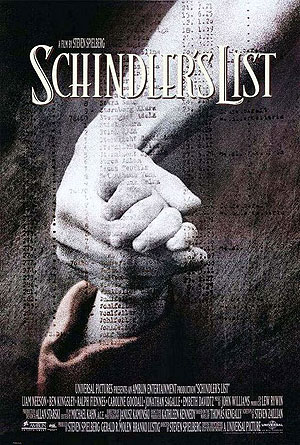

Schindler’s List

SCHINDLER’S LIST (MOVIE)

Universal Pictures

Original release: November 13th, 1993

Running time: 195 minutes

Director: Steven Spielberg

Writers: Steven Zaillian, Thomas Keneally

Composer: John Williams

Cast: Liam Neeson, Ben Kingsley, Ralph Fiennes, Caroline Goodall, Jonathan Sagall, Embeth Davidtz

When Schindler’s List was released in 1993, the film’s documentary realism was at the centre of much of the critical debate. Shot in stark black-and-white and largely stripped of the emphatic score, spectacular visual effects and meticulous storyboarding usually associated with Steven Spielberg’s filmmaking, it was described as the film that “transformed Hollywood’s greatest showman into its finest artist”

However, while the film is indeed a marked departure for Spielberg, the director doesn’t entirely shed his showman’s skin. For all its realism, Schindler’s List is also deeply cinematic, with expressionistic flourishes such as the famed ‘girl in the red coat’ sequence speaking of a man who truly grasps cinema’s poetic potential.

Scenes such as this are used by Spielberg to highlight an emotional truth (in other words, a subjective take on history) as well as a literal one (objective fact), and the tension between the two is at the heart of Schindler’s List. Which is the most honest: emotional truth or literal truth? Which is the most appropriate for history? And which should be used to represent a moment in history as shocking, vital and sensitive as the Holocaust? Spielberg picks emotion, and that’s hardly surprising.

The director’s involvement in the film, which Roman Polanski, Martin Scorsese and Sydney Pollack had all been linked with during the 1980s, was born out of an emotional reaction. Spielberg had fled from his Jewish roots for much of his early life, but as he watched reports of Holocaust denial and the atrocities in Bosnia fill the news, he felt compelled to act.  As much a warning as an act of memorial, Schindler’s List aims to remind us that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”.

As much a warning as an act of memorial, Schindler’s List aims to remind us that “those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it”.

The best way to ensure that audiences do remember is to strike their emotions and the best way to strike their emotions is to communicate in a language they are familiar with. For Spielberg, that language is television and film, and many of the ‘realist’ decisions he made on Schindler’s List (use of black-and-white, for example) were designed to replicate culture’s representation of the Holocaust as much as survivors’ actual remembrances of it.

As he explained at the time,

Spielberg extends the use of such cinematic shorthand to more subtle forms. In one of the opening scenes, we see Schindler at a Nazi party. He sits at a table, alone and distant from the celebrations. Emphasising Schindler’s eyes by subtly highlighting them, Spielberg moves his camera so it calmly and impassively surveys the room, just as Schindler does.

This is not straightforward realism, but a realignment of the audience’s point of view, from objective to subjective. The scene forces us to relate to a character who, at this point in the film, is deeply ambiguous, a hero who is socialising with the enemy. Schindler, like us, is oblivious to the desperation that surrounds him, and his journey through the film’s narrative matches the audience’s as he moves from ignorance to enlightenment.

Is such an emotional approach to history justified? Many have argued no, but Barbie Zelizer says that although “the event as it is retold” must never replace “the event as it happened”, popular culture should not be afraid of trying to represent history and inspiring heartfelt debate.  “The explicit function of popular culture,” she writes, “should be not only to shake up the public and rattle its sensibilities about the past, but also to generate questions about the form of the past”.

“The explicit function of popular culture,” she writes, “should be not only to shake up the public and rattle its sensibilities about the past, but also to generate questions about the form of the past”.

The thousands of pages that have been written about Schindler’s List prove it succeeded in that aim and the unexpectedly high box office shows that it did so on a grander scale than highly regarded documentaries such as Shoah (1985) and Night And Fog (1955). Vital masterpieces though those films are, they are documents rather than films, pieces of evidence that are accessible primarily to those studying the Holocaust. In other words, they preach to the converted, while Schindler’s List gathers a worldwide congregation and refuses to let them leave the church until they’ve been educated.

- Wayne Maser, The Long Voyage Home: Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List, Harper’s Bazaar, February 1994

- Yosefa Loshitzky, Spielberg’s Holocaust, Indiana University Press, 1997

- Joseph McBride, Steven Spielberg: A Biography, Faber and Faber, 1997

Yet Spielberg did more than simply create a significant piece of social education with Schindler’s List – he helped justify his art form. History, Spielberg proved, should not be relegated to textbooks and documentaries. Mainstream and, for want of a better word, ‘cinematic’ cinema can illuminate the past just as well as any purely factual film can. Indeed, it may be even better placed to do so.

As subsequent factual films Saving Private Ryan (1998) (visually inspired by Robert Capa’s Magnificent Eleven photographs) and Munich (2005) (inspired by 70s Hollywood thrillers) proved, Spielberg is still behind the same movie camera he was in 1982, peering at the world through its lens. But it’s no longer an act of cowardice. Instead, he’s using it to make a powerful connection to the past and prove that sometimes films can be more than just films.

Paul Bullock

Paul fell in love with cinema when dinosaurs ruled the Earth. A childhood viewing of Jurassic Park introduced him to the power and wonder of the silver screen, and after his dreams of directing were shattered by crumbling papier-mâché sets, disobedient action figure actors and a total lack of talent, he quickly turned to writing, thus proving that life does indeed find a way.

When not citing scripture from the apostle Ian Malcolm, Paul also enjoys the films of Billy Wilder, Paul Thomas Anderson, Stanley Kubrick, Frank Capra, Martin Scorsese and Werner Herzog. His favourite film is The Apartment and his favourite apartments are in films. They're much cleaner than his.

Paul can also be found talking nonsense on Twitter and his website Quiet of the Matinee. He works through his addiction to a certain bearded director on From Director Steven Spielberg.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA