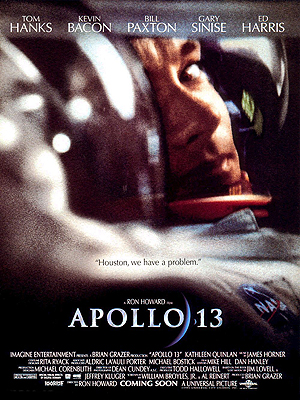

Apollo 13

Universal Studios

Original release: June 30, 1995

Running time: 140 minutes

Director: Ron Howard

Writers: William Broyles, Jr., Al Reinert, Jim Lovell, Jeffrey Kluger

Cast: Tom Hanks, Bill Paxton, Kevin Bacon, Ed Harris, Kathleen Quinlan

“Gentlemen, what are your intentions?” 01:09:25 to 01:12:03

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

There was a time when the whole world looked to the skies in the spirit of adventure and hope, not for reasons of religion, but because mankind had shaken off the bonds of Earth and travelled beyond the limits of our atmosphere – space exploration had begun. Though this spawned the rather paranoia-tainted Space Race between the US and Russia, both trying to conquer the outer limits first, the advances of humanity were of greater import. In 1969, this led to one of the truly great achievements of the 20th Century (or any century) as the crew of Apollo 11 landed on the surface of the Moon. There, astronaut Neil Armstrong produced one of the most famous (if grammatically disputed) quotes in history: “That’s one small step for a man, one giant leap for mankind.” In 1970, the world would receive another now famous quote from another Apollo space mission: “Houston, we’ve had a problem.”

The Apollo 13 space mission became known, rather paradoxically, as something NASA would prefer to forget. It’s understandable to some degree. Success is normally measured by starting with a particular goal, and through perseverance and hard work, achieving that goal, to the credit of those people driven enough to make it happen. Failing to achieve that mission, even if terrible tragedy is avoided in the process, is seen as just that… a failure. After all, what kind of success can you really claim when all you can say is, ‘well, at least no one died’? So, the story of Apollo 13, with its hope buckled by tragic circumstance and pulled back in a perilous rescue, was set to be lost in the popular consciousness, remembered only by those who were there and those burgeoning space nerds who would happen upon the story in later years as they studied their favourite subject. Let’s be honest, if this movie didn’t exist, most of us wouldn’t even know about this story. I sure wouldn’t.

Thankfully, there was at least one space nerd out there who was alive to witness to the events as they unfolded and would come to bring the story to the rest of us, complete with all the tension, drama, defeat and triumph that it afforded the movie-watching public. And that space nerd’s name was Tom Hanks.

Hot off the back of two back-to-back Best Actor Oscars (Philadelphia in 1993 and Forrest Gump in 1994), Hanks could pretty much write his own ticket for any project he wanted to make. So, being the lifelong fan of NASA and space travel, he knew of a particular story that he thought would be perfect for audiences, complete with all the hallmarks of a great story, like hope, tragedy, conflict and ultimate triumph. The Apollo 13 mission was one marked by great tragedy, but perhaps an even bigger tragedy would have been to let this story of genuine heroism and fortitude be lost forever. And so, with the release of this film, directed by Hanks’ old friend Ron Howard, Apollo 13 was once again rescued and given the heroic legacy it deserves.

A big theme of the film, aside from that of victory snatched from the jaws of defeat, is that of a dream denied, which becomes the most tragic aspect of an ultimately grand story of winning against incredible odds. Jim Lovell, the man who led the crew aboard the spacecraft, and is played by Tom Hanks onscreen, was clearly a man enamoured by the Moon and what it stood for. And not for bragging rights, or the socio-political sway it had to win the aforementioned Space Race, but what it meant to the world to have achieved something so profound. It’s something he mentions in his book, and a it’s line that makes it into the film, speaking about Apollo 11 and Neil Armstrong’s famous footsteps: “From now on we’ll live in the world when man has walked on the Moon. It’s not a miracle. We just decided to go.” From lofty ambition and incredible effort comes one of the defining events of mankind, and it’s become a marker for what we can do as a species ever since.

And it’s not lost on us as an audience, just what it means to Lovell personally to actually walk on the surface of the Moon. He flew in Apollo 8, the first mission to orbit the moon, coming so close to its surface… it was right there… almost like he could just reach out and finally touch it. He even named one of its peaks after his wife, Mount Marilyn. Now, on Apollo 13, he’ll finally get to go there, put his footprints next to Armstrong’s, look back at the Earth and share in a view that’s only ever been seen by 12 men in all of history.

However, you can’t have a disaster movie without the disaster, and Apollo 13 has its own. About halfway into the film, there’s a scene which essentially marks the shift in what kind of story’s being told, the thematic trajectory if you will. Beginning as a mission of hope and enthusiasm, the promise of a dream to be fulfilled, it becomes something else, dreams dashed, with the only hope left that the three men in the spacecraft make it back home safe.

By this point, the disaster has struck. Something’s gone horribly wrong, and everyone knows it’s no longer an expedition to walk on the moon, but to survive. The crew have to make a single orbit of the lunar sphere, coming around the dark side of the Moon, using its gravity to slingshot themselves back towards Earth. For a few minutes, they’ll be out of radio contact with mission control, the three men completely cut off from the world, and it will be the closest they will get to their goal.

The spacecraft slides around the surface, two of the men, Fred Haise and Jack Swigert, stare out of the window with longing at something so tantalisingly close. Only Lovell stays back, seemingly unable to bring himself to look, to torture himself by looking on something so close… it’s right there… almost like he could just reach out and finally touch it. Haise relays to Lovell, “Mare Tranquilitatis – Neil and Buzz’s old neighbourhood. Coming up on Mount Marilyn. Jim, you’ve got to take a look at this.” Jim answers, “I’ve seen it.” Haise turns back to the moon, leaving Lovell with his thoughts, and the audience joins him…

The module has landed on the moon, and Lovell makes his way down the ladder and takes his first steps on the Moon. He reaches his hand down and draws his fingers across the powdery surface, making four small furrows in the dust. He walks a little bit in that slightly awkward, bouncy manner, stops and stares back at the Earth, which must surely be one of the most awesome sights ever witnessed by man. And not in the casual sense of the word awesome, used nowadays to describe things like a t-shirt or some really good nachos, but in the classic sense, to be genuinely and truly struck through with awe at the enormity and profundity of looking back at our home planet.

Earlier in the film, Lovell looks up and, holding out his hand, hides the Moon with his thumb. Now, from up here in the damaged spacecraft, Lovell holds out his hand once again, and hides the Earth with his thumb. That’s how close he is.

- [1] Lovell, J. and Kluger, J., 1994. Lost Moon: The Perilous Voyage of Apollo 13. Boston: Houghton Mifflin

- [2] Gardner, D., 1999. Tom Hanks: The Inside Story. London: Blake.

And then comes the moment, the singular moment when Lovell accepts what it must’ve been so hard for him to do. As radio contact returns, and mission control comes back to them, Haise, still staring out the window, admits to his fellow astronauts: “Gotta tell you, I had an itch to take this baby down though, and do some prospecting. Damn, we were close.” Lovell responds, “Gentlemen, what are your intentions?” Haise and Swigert turn to their leader. He continues, “I’d like to go home… We got a burn coming up. We’re gonna need a contingency if we lose comm with Houston. Freddo, let’s… let’s get an idea where we stand on the consumables. Jack, get into the Odyssey and bag up all the water you can before it freezes in there… Let’s go home.”

Here, Lovell accepts that he’ll never get this close to the Moon again, that he’ll never attain that dream. It’s a turning point in the whole film, marking the exact moment the story stops being one of hopes dashed and becomes one of the fight to get home. It’s the moment where the three men acknowledge what is, in essence, a great personal sacrifice for them, made by pragmatism and the need to survive, but taken with grace and dignity. It’s the saddest moment of the film, and it’s what gives depth to the ultimate triumph, marking it is a bittersweet joy.

Paul Costello

Paul Costello is a critic, blogger and former film editor with a degree in filmmaking from the University of the West of Scotland. He’s been watching movies for as long as he can remember, and began the process of writing about every movie he owns on his blog: acinephilesjourney.blogspot.co.uk. He’ll be at that for a while. He’s also the resident film writer at TheStreetSavvy.com.

You can follow him on Twitter @PaulCinephile.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA