Stanley Kubrick

Stanley Kubrick’s films are cold, soulless, disconnected and indifferent. So goes the persistent criticism of the famously reclusive director’s work. That his films exhibit all of these characteristics is, I think, undeniable, but it seems to miss the point – it’s precisely these elements that give them their unique atmosphere, that make them so compelling. A Kubrick film is cold, and this is why we watch it. It’s as close as we get to cinema made entirely by its own machinery, just as factory robots are made by other factory robots.

Stanley Kubrick on set, 1968

Stanley Kubrick on set, 1968This concept is a frightening one. The romantic in us shudders at the idea of art being made by machine, without ‘heart’, without ‘soul’. Yet at the same time the vast majority of cultural production – soap operas, game shows, bubble-gum pop, and so on – is remarkably formulaic and hackneyed and very probably could be generated by a computer program, if it isn’t already. The KLF famously applied such a philosophy in the making of their number one hit Doctorin’ The Tardis in 1988, and there are countless books about how to write screenplays or novels. Think about some iteration of a long-running action franchise and how you’re your brain wearily counts off the beats in the plot progression to the predictable dénouement. All art is to some extent craft – the 99 per cent perspiration, if you like – and all craft is learnable in a logical, sequential way, and therefore assimilable by technology.

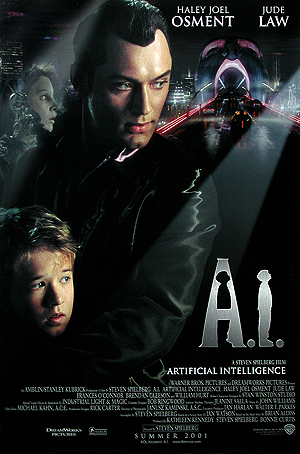

But, for all that, I’m not pedalling the usual apocalyptic argument that a day is going to come when films will actually make themselves, when the machines rise up and rebel against their creators. This paranoid attitude to technology has been with us ever since Frankenstein, and dominated much of the science fiction genre ever since, including Kubrick’s takes on it – Hal 9000 in 2001, the robots in A.I. , the artificial hand of Dr Strangelove in rebellion against the man himself.

No, what I’m suggesting is that Kubrick understood in a way that few directors ever have that the medium of film is a technological art, it is primarily art made by machines.

Dr Strangelove, dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1964

Dr Strangelove, dir. Stanley Kubrick, 1964The writer only needs chalk, the musician her voice, the painter the wall of a cave. They all use tools so basic as to have enabled artistic production in these media for millennia. The director, on the other hand, uses equipment whose sophistication is wholly dependent on the milieu from which it sprang – mass industrialization, with its concomitant forces of mass production, mass consumption, mass education, mass media and, let us not forget, mass destruction…

In contrast to the simple and immediate production of most arts, film requires either drawn-out and often fraught collaboration, or else directors who have something of the mad scientist about them, grand manipulators, Svengalis with a taste for dictatorial pleasures. They surround themselves with multi-million pound state-of-the-art tools fashioned in the clinically-lit laboratories of uber-modernity, yet such figures also remain imbued with something mystical, the spirit of the alchemist, the necromancer.

Kubrick’s pathology saw him both seduced and repulsed by technology at the same time. He loved and obsessed over the technical aspects of film-making; the lighting techniques, the architecture of set construction, the sound-recording equipment, the camera itself – in short, the gadgets. But he also felt that machines were not to be trusted – he insisted, for example, on being driven no faster that 35mph and simply refused to fly once he’d settled in his discrete country pile in the English shires, making his few trips to the US via boat.

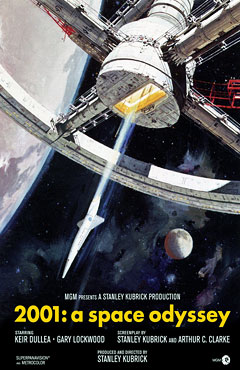

2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968, dir. Stanley Kubrick

2001: A Space Odyssey, 1968, dir. Stanley KubrickThis techno-paranoia is explored most vividly in 2001, with Dave Bowman at the mercy of the computer Hal 9000 as he drifts towards Jupiter, forced to disable it

– to regress, technologically-speaking – in order to survive. You get to wondering if Dave Bowman’s predicament isn’t also Kubrick’s. Here was a man who had succeeded in wrestling complete control over every aspect of the film-making process, and on a ‘blockbuster’ scale few directors have ever achieved, but it was a success that left him alone with the technology, like the last ghost in the machine. Yes, there were lots of other people involved in his productions, but to Kubrick they were often mere ciphers, little more than machines themselves, a criticism levelled against him by many of those who found themselves being used that way. Gilbert Taylor, the Director of Photography on Dr Strangelove spoke of his interview for the job being something like an exam, Kubrick sitting opposite him with a checklist of questions to do with technical processes. You get the sense that Kubrick saw other people as information sources to be downloaded, or as Adrienne Corri put it, “a vampire on people’s brains.”

His mania for control was such that in the making of Barry Lyndon and subsequent films he demanded that every shot location be within driving distance of his home. He became obsessive about keeping notebooks, photographs and files on every aspect of production. ‘I don’t trust people who don’t write things down,’ he said. ‘Many people feel it’s beneath their dignity to take notes, and try instead to trust their memories. I don’t work with them.’

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, dir. Stanley Kubrick, 2001

A.I. Artificial Intelligence, dir. Stanley Kubrick, 2001His estate was famously full of mountainous boxes of material, like an exclusive Kubrick search engine, where every potential permutation of a production was played out. Kubrick the brilliant and obsessive chess player was engaging in a process of logical sequencing much like that of a computer. Malcolm McDowell, his lead in Clockwork Orange, remarked that, “Stanley could never understand the human element. If he could only eliminate that, he could make the perfect movie.”

But computers crash. They have their own inherent flaws, their own breakdowns. The most haunting words in the whole of 2001 are spoken by Hal 9000, repeated over and over, as Dave Bowman desperately tries to shut it down. ‘My mind is going,’ it says, ‘my mind is going…’ During this sequence there’s a constant hissing sound, like oxygen escaping from an air-tank, the sense of something leaking away, a slow and suffocating death.

Technology is never neutral. It’s all the product of human labour, developed for human needs and desires – survival, power, profit, pleasure. The history of the movie camera owes its invention, at least in part, to the invention of the machine gun, the stepping-stone from one to the other being Etienne-Jules Marey’s chronophotographic gun, an adapted machine gun capable of taking 12 still frames a second, and revealing aspects of motion – in a leaping man or a running horse, for example – never seen before by human eyes. Technology had asserted itself with such force that time could now be prodded and dissected like a splayed frog. The impact of this was revolutionary, so all-encompassing that today it’s impossible to see outside it. It marks a fissure in history’s continuum that feels unbridgeable.

- [1] John Baxter Stanley Kubrick: A Biography (1998), Harper Collins

It strikes me that Kubrick as a director was forever pre-occupied with this cinematic ancestry, both in terms of the content of his films and in his attempts to assimilate himself into the technology that creates that content. “When we hand over our money to see a Kubrick film,” writes the biographer John Baxter, “we are buying his eyes.” And what Kubrick’s eye reveals is the effect of technological saturation on modern lives, how receiving information and images at such speeds gives our daily lives a strange, often hallucinogenic sheen, full of bizarre edits and correspondences, uncanny synchronicities, moments where we can’t tell memory from fabrication. In the vast inhuman circuitry of the modern megalopolis, we have become alienated and atomized figures, fractured identities that could be wiped out in an instant if the media mainframe supporting it were to suddenly and irrevocably crash.

This is Kubrick’s world, and if it is cold, paranoid, disconnected and indifferent, it is also representative, and this is why Kubrick’s films are so wrought with cultural resonance, and why, despite the criticisms repeatedly levelled against him, they remain so enduring.

Robert Bright

Robert Bright has been working as a journalist since the early 1990s, and such is his vintage, he remembers seeing Goodfellas at the cinema, a film that remains one of his favourites, and its director Martin Scorsese one of his heroes.

He is interested in film noir – particularly such classics as The Maltese Falcon and Out Of The Past – and American science-fiction B-movies of the 1950s, like Howard Hawks’s The Thing. Other favourites, taken at random, include Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad And The Beautiful, John Ford’s The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, Steven Spielberg’s Jaws and Stanley Kubrick’s 2001: A Space Odyssey.

You can follow him on Twitter at @MKUltraBright.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA