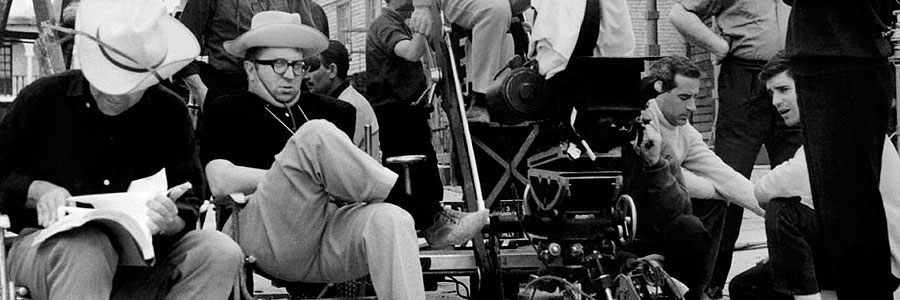

Sergio Leone & The Game of Death

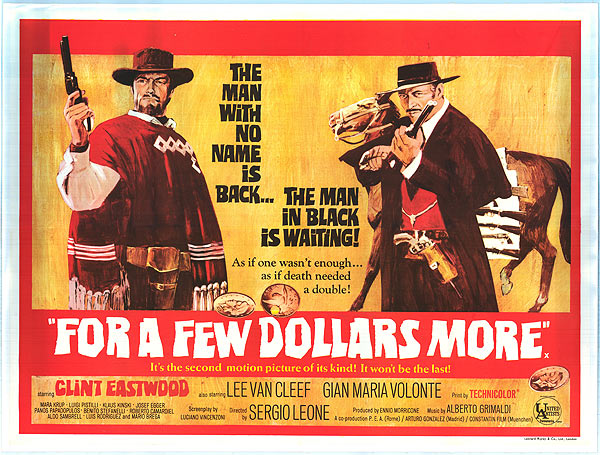

In a scene from For A Few Dollars More (1965), Clint Eastwood’s gunslinger Monco wants to get rid of the avuncular bounty hunter Colonel Douglas Mortimer, played by Lee Van Cleef, and the feeling’s mutual. They’re both on the trail of Gian Maria Volante’s fugitive El Indio and his outlaw band and they don’t mean to share the reward, nor do they want to kill each other necessarily. First the hotel porter is press-ganged into removing the luggage, but understandably panic-stricken about being caught in the middle of a gunfight, he drops the bags and high tails it. The two gunfighters then get serious and this is where things get funny. First, Monco steps on Mortimer’s foot, dirtying his boot, and then Mortimer returns the gesture. Monco punches Mortimer in the face. Here there’s comedy in the sudden outburst of violence. The shortcut that short circuits a certain decorum.

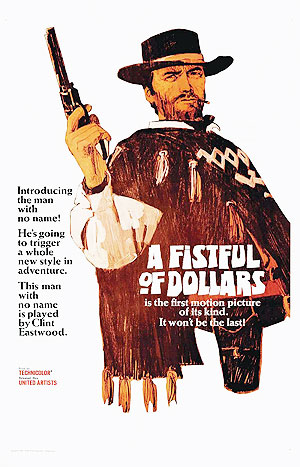

Fistful Of Dollars, dir. Sergio Leone, 1964

Fistful Of Dollars, dir. Sergio Leone, 1964It’s typical of all of Eastwood’s appearances in Leone films. He’s the character who bends the rules. This is a game that can only go so far. The violence that it contains and restrains is still there and can burst out once patience has been exhausted and there’s no other avenue to pursue. Mortimer – an older and cooler man – doesn’t rise to the bait but picks himself up and goes to retrieve his hat at which point, just as Mortimer’s hand is on the hat – bang! Monco shoots and fires the hat out of reach. And of course this is repeated. Twice. Mortimer’s had enough and now it’s his turn. He shoots Monco’s hat off his head but Mortimer – with a one-upmanship – doesn’t even let the hat touch the ground. Every time the hat seems to be falling Mortimer shoots again and weeeee (with a typical Morricone touch on the soundtrack) up the hat goes into the night sky. Apparently, honour has been satisfied, the limits of silliness reached and breached and the two men can go back to the hotel and thrash out a deal to form an alliance and share the booty.

The whole scene has been watched by an audience within the film, a bunch of urchins hiding under the raised sidewalks of the town and providing a commentary on what we are watching. ‘See,’ one of them says. ‘They play the same games we do.’

Such a comment makes obvious sense. Children (or more accurately boys) play at these games of violence and simulated violence all the time. But the games themselves are based on adult realities. The gunshot noises that so frequently issue from title sequences and from the films themselves even sound close to the imitations of the kids’ ‘peow’.

For A Few Dollars More, dir. Sergio Leone, 1965

For A Few Dollars More, dir. Sergio Leone, 1965Mortimer and Manco are playing the game of seeking a provocation. The phrase describing someone with ‘a chip on their shoulder’ comes from the forced pretext of a fight. You place a chip (a stone or woodchip) on your shoulder and then tell the person you want to fight to knock it off. A challenge a dare. This has the advantage of getting them nicely in range. Drawing a line in the sand dates back to Roman times when a Roman envoy drew a circle in the sand around a belligerent king and icily instructed him to come to terms before stepping out of the circle. Likewise, throwing down the gauntlet comes from the times of chivalry and knights on horses.

The children’s games are rehearsals for the seriousness of actual conflict but the adult manoeuvres retain the childish arbitrariness of earlier times. All of Leone’s films have a sense of playfulness, but the playfulness shouldn’t be conflated with joyfulness, or being carefree. The play is serious and by being at the same time structured so as to rhyme with the cosmic joke is grimly witty. For A Few Dollars More is perhaps the film that shows violence at its most game-like.

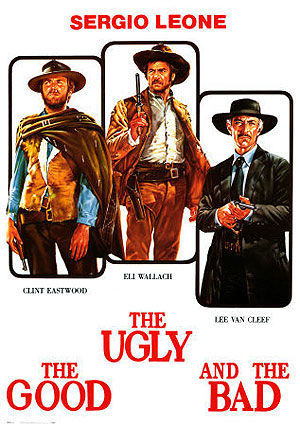

Gunfights in Leone’s films are all about ritual, or a comic jumping the gun of ritual. His heroes are men who play by the rules, bend the rules (Eastwood), or break the rules (Eli Wallach’s Tucco), but the rules are always there. The stand off is a form of dueling. The two opponents stand at a set distance. Blondie (Eastwood) is introduced in The Good, The Bad And The Ugly (1966) squaring off to three opponents.

‘A couple of steps back,’ he quietly tells his nearest adversary and the man obliges. In the finale of the film, the three men of the title will use the widescreen aspect as their marks. As Christopher Frayling’s noted in his magisterial Spaghetti Westerns: Cowboys and Europeans from Karl May to Sergio Leone (Routledge, 1981), the violence itself is always quick, punctual, beginning and ending at the same time. Leone lingers on the deferral of violence and then when it happens, despite taking an age to get there, it paradoxically seems to be over before it’s begun. All overture with a short sharp crescendo.

The Good, The Bad And The Ugly, dir. Sergio Leone, 1966

The Good, The Bad And The Ugly, dir. Sergio Leone, 1966In For A Few Dollars More the length of the wait before the shooting begins is dictated by El Indio who uses a locket which plays a tune. Once the tune’s over the shooting can begin, but El Indio has the obvious edge because he is familiar with the slow wind down of the tune and so is prepared to fire the instant it finishes whereas his opponent will perhaps wait a fatal second. Manco confuses him because he has an identical locket that he has stolen from Mortimer. And of course Mortimer – as brother of the murdered sister who owned the locket is also familiar with the tune, thus eliminating El Indio’s advantage.

Being fast in a Leone film isn’t enough – everyone’s fast: even the weed smoking El Indio – there has to be an edge. Weirdly Leone’s evil characters aren’t rule breakers so much as adherents who allow for no compromise. Angel Eyes ‘always sees the job through’ once he’s paid; El Indio always waits till the end of the tune. Prior to that in Fistful Of Dollars (1964), Ramòn (Gian Maria Volante once more) is brought down because he sticks rigidly to the rule ‘always aim for the heart’. In contrast, Leone’s heroes are always willing to bend or break the rules. Joe (Eastwood) wears an iron vest to protect him from the bullets; Manco puts El Indio off with the stolen locket and Blondie in The Good, The Bad And The Ugly will win the final gunfight by emptying one of his opponents’ guns.

Cheating can only happen within the formal structures of violence that Sergio Leone and his characters have established. The game must be played out to the end. The poster for The Good, The Bad And The Ugly says it all: ‘For three men the Civil War wasn’t Hell. It was practice.’

—–

Part 1: The Game of Death

Part 2: Sergio Leone & Women

Part 3: The Man with No Name

John Bleasdale

John Bleasdale is a writer based in Italy. He has published on films at various internet sites and his writing can be found, along with blog posts, collected at johnbleasdale.com.

He has also contributed chapters to the American Hollywood and American Independent volumes of the World Directory of Cinema: (Intellect), Terrence Malick: Films and Philosophy (Continuum) and World Film Locations: Venice (Intellect). You can also follow him on Twitter @drjonty.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA