Fritz Lang

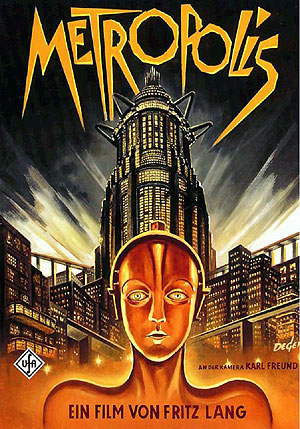

Metropolis, dir. Fritz Lang, 1927

Metropolis, dir. Fritz Lang, 1927The evolution of extralegal retribution does more than simply expose the often targeted inadequacy of the justice system, it appeals to a moral sense of comeuppance which courtrooms and prisons fail to provide. Its history speaks to the raw ethical code of individuals and a feeling that justice has been evenly dispensed. Perhaps it’s ironic then that such moral sensibilities can be found in Fritz Lang’s films, a director who was famously dubbed the ‘Master of Darkness’ by the British Film Institute.

Oddly, mob rule has always been a defining characteristic of civilisation, from the reign of the Roman Empire to the days of witchcraft and lynching. Slowly, its outlook was gladiatorialised as across the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries; vigilantes stood against crime and banditry before dangerously wandering into racial and nativist violence. Today, we look to the Internet groups of Anonymous and LulzSec who have turned hacktivism into a form of online browbeating.

It’s unclear whether a sense of revenge brewed within Lang after he served his country in WWI, but it sparked a defiant sobriety to his writing which stemmed from desolate circumstances. The dystopian environment of Metropolis (1927), a film which predated Orwell’s classic Nineteen Eighty-Four by over two decades, and even Huxley’s Brave New World, indicated Lang’s dissatisfaction with how society was progressing.

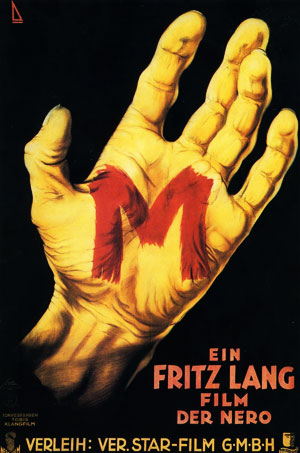

In it, Lang explores a futuristic city divided by a ruling, intellectual elite and an underground army of workers. After mad scientist Rotwang (Rudolf Klein-Rogge) claims he will resurrect the wife of the city’s leader by building a robot, he disguises it as a younger woman from the underground, Maria (Brigitte Helm). The robot provokes widespread violence and convinces the workers to rise up and destroy the industrial machinery which powers the city. It’s an early instance of the class divisions which Lang would continue to investigate throughout his career, particularly in M (1931) as he venerates the homeless community, but also hints at how he believed revolution may well be the sole key to overthrowing regimes.

M, dir. Fritz Lang, 1931

M, dir. Fritz Lang, 1931Lang also uses Metropolis to expose a blind herd-mentality to collectives, a sense of moral outrage and social panic which can produce revolutionary effects but, simultaneously, dire consequences. He alludes to this in Fury (1936) as a lynch mob faces incarceration after burning down a prison where an innocent man has been jailed. It’s clear that Lang is wrestling against a general suspicion of organised chaos but also an admiration of its power and utility. After the workers destroy the ‘heart machine’ in Metropolis, the underground tunnels flood, threatening to drown their children. The fact that the robot Maria is able to rouse and galvanise the workers so easily does two things for Lang…

The first is that it allows him to suggest that members of the working-class frequently live on the brink of rebellion, perhaps parodying the level of relative stability in the German economy throughout the mid-1920s, but also serving as a prophetic glance towards the impending decline of the 1930s. The second is that Lang can use the robot Maria to criticise autocracies, how one individual can spur an entire community to follow them on a whim. It’s remarkable really how farsighted Lang’s critique would be, appearing six years before Adolf Hitler’s arrival as the Chancellor of Germany.

In a sense, Germany lost a great deal when Lang fled to Paris and subsequently America. The industry bid adieu to an original master producing work which reached far into the psyche of the European filmmaking tradition, concerned with auteurist aesthetic, reflective political commentary and fusion of noir filmic modes. His understanding and critique of Germany’s progression was the last remaining symbol of vision before the end of the WWII, which brought about a generation of confusion and unrest as filmmakers and artists grappled fiercely with the ideas of guilt, responsibility, reconstruction and newly established identity.

- Bergvall, Åke. 2012. Apocalyptic Imagery in Fritz Lang’s Metropolis. Literature/Film Quarterly. [online] Vol: 40. Issue: 4. Page no. 246+. Salisbury University Press. [Accessed 23/11/2012].

- Smith, Susan. 2005. Metropolis: Restoration, Reevaluation. CineAction. [online] Issue: 66. Page no. 12+. [Accessed 23/11/2012].

These films remind us of an era of truly controversial and progressive imperatives which were sealed to the core of art-house filmmaking.

They can be intimidating (almost as much as Lang’s bullish reputation), particularly his Dr. Mabuse films which could have endless books written on them. But they deserve so much praise. They characterise the true European intelligentsia outlook on society itself and display how blackened a world can be when it yields to the processes of class, politics and hoggish lawmaking.

Andrew Latimer

Andrew started out writing theatre reviews in Edinburgh while studying for a degree in Arts Journalism. His interest in film came after attending several festivals across the UK. In particular, he discovered a love of documentary cinema, specifically the work of Werner Herzog and Errol Morris.

Andrew loves films which investigate stories of undocumented struggle and solitude. Some favourite docs include Grizzly Man, King of Kong, 5 Broken Cameras, L'encerclement, Inside Job and Shoah.

Andrew runs a Scottish arts review website, TVBomb, and you can follow him on Twitter at @ajlatimer.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA