Mulholland Drive

Universal Pictures

Original release: November 18th, 2001

Running time: 147 minutes

Writer and director: David Lynch

Composer: Angelo Badalamenti

Cast: Naomi Watts, Laura Harring, Ann Miller, Dan Hedaya, Justin Theroux

“Someone is in trouble” 01:00:07 to 01:01:51

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

The front door occupies a curious place in all our lives. It’s what separates us from the outside world; our portal between our interior lives and the external. When someone unexpected comes a knocking, it can be a disconcerting, unsettling experience. This could be a door-to-door sales person (we’ve all turned them away), a police officer with some bad news or perhaps just someone with the wrong house number.

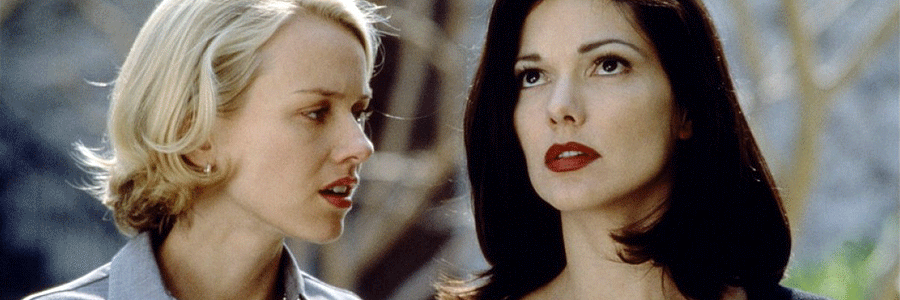

In David Lynch’s Mulholland Drive, an unexpected visitor is the catalyst for one of the film’s most memorable scenes. Naomi Watts plays two characters: Diane, a washed up Hollywood actress, and Betty, a young up-and-coming star. Diane escapes into the subconscious fantasy life of Betty in order to suppress her guilt at hiring a hitman to kill her ex-lover, successful actress Camilla (Laura Harring), out of sexual jealousy. In this fantasy world, Betty meets Rita (also played by Laura Harring) and they embark on a mystery trail that ultimately destroys Diane’s fantasy life as Betty, leading her back to guilt-ridden reality.

Following so far?

The egoic boundary becomes increasingly blurred as we struggle to distinguish between the worlds of fantasy and reality; Betty and Diane. In Diane’s fantasy world where she’s this rising star Betty, numerous shadowy figures disrupt the ‘ideal ego’ of Betty in order to push Diane back towards facing her guilt in reality. The ominous figure of The Cowboy (Lafayette Montgomery) seemingly directs characters as he sees fit, metaphorically stating: “Let’s just say I’m driving this buggy, and, if you fix your attitude, you can ride along with me.” Later in the film, he directs Diane out of her self-created fantasy world with the simple line: “Hey, pretty girl. Time to wake up.”

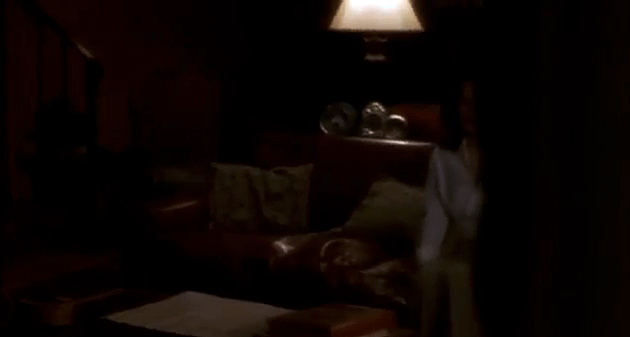

Yet for me, Lynch’s mastery of this psychological disruption is not best portrayed in the memorable figure of The Cowboy, but in a brief scene an hour into the film, when an old woman knocks on Betty’s door. Lynch does all he can to alert the audience that something’s psychologically amiss in this scene.

Upon Betty’s opening of the creaky front door to this strange hooded figure, Lynch introduces what can best be described as ominous ambience, extremely similar to that used during the superimposed appearance of the Mystery Man in Lost Highway. This is a clear indication of the imminent disturbance in Diane’s fantasy. In a rather telling piece of imagery, Bonner’s face is half-hidden in shadow beneath her hood, suggesting a ghostly, almost Macbeth-esque witch-like quality to her character; an interpretation only reinforced when she begins her disjointed, prophetic speech:

Someone is in trouble. Who are you? What are you doing in Ruth’s apartment?

Lynch frames the shot of Bonner to show little of the courtyard in the background. In fact, preceding the arrival of Coco – Betty’s landlord – and the return to ‘normality’ (at least within the context of the fantasy), the shot of Bonner becomes even tighter and more draped in shadow as Betty continually attempts to rid herself of the disturbance in her fantasy. The reverse shot of Betty encompassed by complete black, combined with Bonner’s increasing occupation of the frame, suggests an almost physical breakdown of surroundings: Diane’s fantasy as ‘Betty’ is seemingly failing here. Lynch does all he can to ensure that we are left with only Betty, Bonner and darkness in this purposefully enclosed encounter. Nevertheless, Diane continues to sustain the subconscious Betty fantasy:

She’s letting me stay here. I’m her niece. My name’s Betty.

BONNER:

No it’s not. That’s not what she said. Someone is in trouble, something bad is happening!

Bonner’s rejection of the name ‘Betty’ – Diane’s fantasy name – marks a direct challenge, by this imposing Jungian shadow, of the ego and the whole subconscious fantasy. A name forms a crucial part of personal identity, a symbolic agreement between the individual and the society which recognises and associates him or her with it. To have someone reject it outright is pretty darn creepy.

I’m sorry, but I don’t know who you are, and I…

COCO:

[arriving] Louise? What are you doing Louise?

If we apply some narrative coherence to Lynch’s story, we can infer that this ‘someone in trouble’ is Camilla (Rita in the fantasy) who, outside this fantasy world, is pursued by a hitman hired by a jealous Diane. This is further confirmed as Bonner, being led away by Coco, attempts to glance at Rita, leaving us with the menacing line: “No, no she said it was someone else who was in trouble.” Within this fantasy world, the arrival of Coco out of the blue, with the convenient excuse of “just delivering some faxed pages of a scene for her [Betty’s] big audition tomorrow”, can be interpreted as Diane’s subconscious attempt to combat the shadow aspect’s confrontation with the fantasy. Recomposing the scene’s surroundings as Coco arrives, Lynch pulls the camera back to a wider shot while Bonner steps back, corrupting her mysteriousness by revealing her face in the porch light.

From this moment on, the disturbing ambience dissipates and we return to a sense of normality, but an unsettling feeling lingers. Was Louise Bonner simply a rambling old woman, or a prophetic witch summoned from the depths of Diane’s guilty conscience?

- [1] Elsaesser, Thomas & Buckland, Warren. ‘Cognitive theories of narration.’ Studying Contemporary American Film: A Guide to Movie Analysis. London: Arnold, 2002. 168-194.

Thomas Elsaesser and Warren Buckland note that “Lynch uses the cinema to express non-rational energy in tangible form (visually and aurally)” and that his films “evoke a ‘return from the repressed’” ¹. The scene with Louise Bonner in Mulholland Drive perfectly exhibits Lynch’s mastery for portraying such ‘non-rational energy’ on screen. His ability to visualise psychological disturbances with such simple scenes – a stranger knocking on the door – is, in my opinion, unmatched.

Maybe it’s just me, but I think there’s something inherently disturbing about an old woman who knocks on your door and threatens your entire world.

James Arden

James is a recent English Literature graduate from the University of York. During his time at university he took as many film-related modules as possible, balancing his studies of Dickens and Shakespeare with healthy doses of David Lynch and Orson Welles. He’s drawn to auteuristic and controversial filmmakers; a far-reaching interest that extends from the colourful, retroistic aesthetics of Wes Anderson to the disturbing yet engaging films of Lars von Trier. Somewhere inbetween lies a love for Polanski, Kubrick and P.T. Anderson.

James is also a filmmaker and film journalist. Follow his work on his website and follow him on Twitter @jnarden.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA