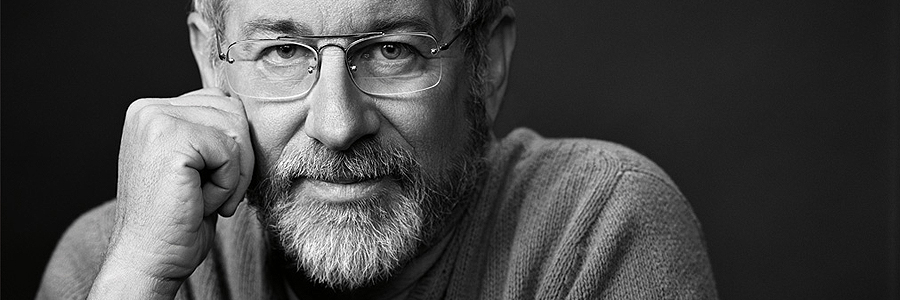

Steven Spielberg

It’s 1952 and a young Steven Spielberg is about to see the greatest show on earth. The boy’s father, Arnold, has taken his son to see Cecil B. DeMille’s extravagantly-titled circus movie of the same name, but when Arnold suggested the trip, the boy didn’t hear the word ‘movie’. He thinks he’s going to see a real-life circus with real-life lions, elephants and clowns. None appear.

Steven Spielberg

Steven Spielberg“So the curtain opens and I expect to see the elephants and there’s nothing but a flat piece of white cardboard, a canvas,” Spielberg has remembered. “For a while I kept thinking ‘Gee, that’s not fair, I wanted to see three-dimensional characters, and all this was flat shadows, flat surfaces… I was so disappointed by everything after that. I didn’t trust anybody. I never felt life was good enough, so I had to embellish it.”

This quote is key to understanding Spielberg’s filmmaking. As much as the ideas we commonly consider ‘Spielbergian’ (suburban wonderment, daddy issues, Peter Pan complexes) cinema is also a hugely significant theme in the director’s oeuvre. It’s why his films are so visually-driven and why film references – Vertigo in Jaws, Goldfinger in Catch Me If You Can, Gone With The Wind in War Horse – appear in so many of his works.

Spielberg’s use of cinema is no mere in-joke though – he uses cinema as a symbol of embellishing and controlling reality. For a time, that control worked. Debut feature Duel is a directorial tour-de-force that finds Spielberg making expressive use of point of view, aligning us with our protagonist, beleaguered suburbanite David Mann, so we can share his anxiety and ultimately his triumph.

Jaws, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975

Jaws, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1975The same is true of Jaws, particularly in the scene where Chief Brody powerlessly watches on as a young boy is killed by the shark. Here Spielberg strips away non-diegetic sound and covers the camera when Brody’s view is blocked, so we only hear what Brody hears and see what he sees. We’re not just watching the film – we’re in it.

Both Duel and Jaws are about weak men who become strong, and are the products of a wimpy, picked-on boy whose father was often absent with work. They draw the audience in through point of view and therefore make us feel as strong as Mann and Brody become by the conclusions of their stories. Spielberg himself is no different. Dissatisfied with his masculinity, he embellished it. He directed a new one.

It’s not only masculinity that Spielberg sends through his cinematic filter though. Having tasted disappointment with The Greatest Show On Earth, the director wanted to make sure that nobody would be disappointed by his films and so the spectacular endings of Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, Raiders Of The Lost Ark and E.T. are designed to break down the “white cardboard” between film and viewer.

Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, 1977, dir. Steven Spielberg

Close Encounters Of The Third Kind, 1977, dir. Steven SpielbergIn all these films, the finales take place at a location that resembles a movie set, with lights, cameras (except in E.T. ) and crowds of people gathering around a wondrous sight. These fictional viewers provide a path into the film for the real ones sitting in the auditorium. Roy Neary, Indiana Jones and Elliott’s awe reflects our own, so we are all unified in one world watching with wonder as the Mothership descends, the Ark takes its revenge and E.T. flies back home.

Such magical moments make it easy to pigeonhole Spielberg as a weaver of simple pleasures, but the director is both in love with and repulsed by cinema – the Ark, for example, takes terrible revenge on those who seek to manipulate it for their own ends. Cinema is an escape, but it’s also a prison able to enslave those who fall too hard for its siren song.

Spielberg learned this lesson the hard way on the set of The Color Purple. He and Alice Walker, on whose book the film is based, were discussing how to bring it to screen and Spielberg mentioned that one of his favourite films is Gone With The Wind. Speaking of her horror at the conversation, Walker said:

Empire Of The Sun, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1987

Empire Of The Sun, dir. Steven Spielberg, 1987So in love with Gone With The Wind‘s cinematic sweep was Spielberg that he’d neglected to understand how the film’s racial politics are viewed by others. Cinema had blinded him, but now he’d had his eyes opened, he wouldn’t make the same mistake again. Gone With The Wind appears in his next film, Empire Of The Sun, but its depiction is hardly positive.

An adaptation of JG Ballard’s autobiographical novel, Empire focuses on a young boy called Jim as he’s separated from his parents during the Japanese invasion of Shanghai in 1941 and eventually finds himself interred in a prison camp. During the invasion, Jim wanders the streets alone, eventually stumbling across a billboard.

Initially, Spielberg shoots the encounter with a medium close-up, framing Jim against a small section of the billboard, which depicts a scene of conflict. It’s a romanticised image and in the context of the all-too-real violence Jim has seen in Shanghai, this fictional representation of battle seems ludicrous, even offensive.

Next, Spielberg shoots the billboard with a wide shot. It’s a poster for Gone With The Wind, and Jim is utterly beguiled. Romanticised it may be, but this epic image is a small moment of comfort in an otherwise terrifying world, and Jim stops to take in its wonder. It doesn’t last long though. Suddenly, a mugger appears in the foreground. Real threat has once again entered the boy’s life, and the comfort offered by Gone With The Wind is diminished.

Schindler’s List, 1993, dir. Steven Spielberg

Schindler’s List, 1993, dir. Steven SpielbergIt’s easy to see 1993 as the pivotal year in Spielberg’s relationship with cinema, and Schindler’s List‘s unflinching realism, combined with Jurassic Park‘s postmodern deconstruction of blockbusters, puts across a good argument for that being the case. However, I would argue that 1993 represents a mere evolution of what Spielberg started in Empire Of The Sun.

The billboard scene isn’t the film’s only reference to cinema and fantasy. Empire is the story of a boy who seeks comfort in fantasy by picturing the adults in his life as comic book characters and violent incidents as slow-motion-fuelled action extravaganzas. In the final scene, he’s reunited with his parents, but is a shell of his former self. So deeply has he immersed himself in fantasy that Jim’s never allowed himself to participate in reality, making his switch from boy to man almost impossible.

With Schindler’s List, Spielberg would have no problem on that count, but of the two films he made in 1993, the Holocaust drama is not the one that would dictate the rest of his career. Jurassic Park is an undoubtedly inferior film, but it shares many of Schindler’s List’s themes and strikes a balance between the escapist fantasy he perfected in the 70s and 80s, and the more dramatic ideas he explored in Empire Of The Sun.

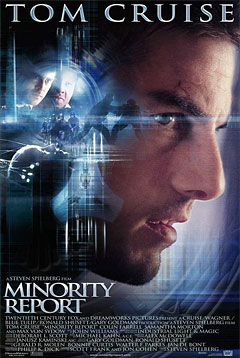

Minority Report, dir. Steven Spielberg, 2002

Minority Report, dir. Steven Spielberg, 2002Jurassic Park is about control – controlling nature, controlling other people through entertainment and controlling your life by keeping responsibility out of it. All of this is ultimately undone by the chaos of reality and it’s only when the characters find balance (symbolised by the closing shot of a helicopter and a flock of birds – the man-made and the natural – flying side-by-side) that they escape the island. With his 1993 double, Spielberg was well on his way to finding that balance.

It wouldn’t be until the turn of the millennium that he’d consistently achieve it though. Despite Amistad and Saving Private Ryan ensuring that the 90s became known as Spielberg’s historical drama period, only one of the seven films he directed between 2001 and 2008 turned out to be a drama (Munich); the others are genre films (sci-fis, capers, comedies, adventure romps) that, like Jurassic Park, lace their fantastical plots with serious and often bleak themes.

A.I., Minority Report and Catch Me If You Can, for example, all make overt references to cinema (Pinocchio, film noir and 60s caper films respectively) and their protagonists attempt to exert control over their world by embracing the kind of fantasies cinema represents. But they become so consumed by their dreams that they neglect to see the damage they’re doing to both themselves and society as a whole. Embellishing reality, Spielberg had learned, is an act of destruction as well as creation.

Though it’s still young, Spielberg again seems to be evolving his themes this decade – this time by looking back. Heritage has been the watchword for Tintin and War Horse, with Captain Haddock unlocking the secret of the Unicorn only after remembering his ancestor, Sir Francis Haddock, and Albert reconnecting with his father only after experiencing the horror of battle, as he had. Lincoln, reportedly loaded with parallels to the modern day, seems likely to follow this trend.

- Steven Spielberg: A Biography (Second Edition), Joseph McBride. University of Mississippi Press, 2010

It’s telling that War Horse brought Gone With The Wind back to Spielberg’s storytelling. In what increasingly appears to be the dying days of celluloid, Spielberg is mounting a passionate defence of the medium with his current crop of films. He’s asking us to look back, on both the history of the world and the history of film, and consider where we are and where we’ve come from. It’s only then, he suggests, that we can decide where we’re going – both as people and as film lovers.

The balance he found in the Noughties is continuing into this decade, richer, more complex and more vital than before. Film doesn’t have to be either entertainment or education, an attempt to embellish the real world or a determined bid to confront it – it can be both. And so it’s come to pass that the man who was so disappointed by cinema in 1952 is now, 60 years on, making sure that cinema is not just the greatest show on earth – he’s making sure it’s the most important one too.

Paul Bullock

Paul fell in love with cinema when dinosaurs ruled the Earth. A childhood viewing of Jurassic Park introduced him to the power and wonder of the silver screen, and after his dreams of directing were shattered by crumbling papier-mâché sets, disobedient action figure actors and a total lack of talent, he quickly turned to writing, thus proving that life does indeed find a way.

When not citing scripture from the apostle Ian Malcolm, Paul also enjoys the films of Billy Wilder, Paul Thomas Anderson, Stanley Kubrick, Frank Capra, Martin Scorsese and Werner Herzog. His favourite film is The Apartment and his favourite apartments are in films. They're much cleaner than his.

Paul can also be found talking nonsense on Twitter and his website Quiet of the Matinee. He works through his addiction to a certain bearded director on From Director Steven Spielberg.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA