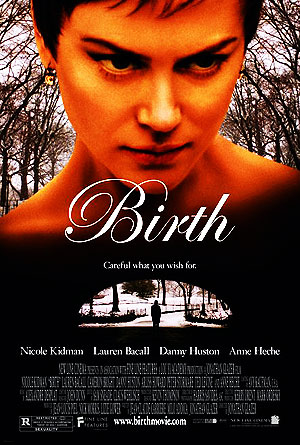

Birth

New Line Cinema

Original release: September 8th, 2004

Running time: 96 minutes

Director: Jonathan Glazer

Writers: Jean-Claude Carrière, Milo Addica, Jonathan Glazer

Composer: Alexandre Desplat

Cast: Nicole Kidman, Cameron Bright, Danny Huston, Lauren Bacall

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

Like Vertigo (1958), Birth was a failure when it was released, panned by critics and seemingly inaccessible to audiences. Like Vertigo, it’s a film about obsession, about repetition, about projection, about grief. Like Vertigo, I predict it will continue to gain in stature as the years pass and as more and more people discover it.

I first saw this film on DVD, late one night, not expecting to like it much since the critical and public reception had been so poor. Still, from its very beginning it hooked me in a way that few films have—a combination of literate screenplay, wonderful acting, exquisite direction, and a glorious score by Alexandre Desplat.

The movie begins with the quote above, a man’s voice speaking over black, seemingly the end of a lecture. The man describes his love for his wife as that thing which would make him doubt even his scientific principles, the power of love being strong enough to push beyond our logical reasoning.

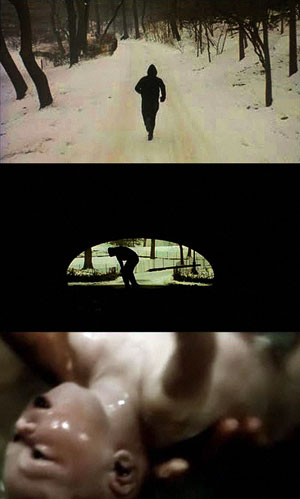

This is followed by one of the most mesmerizing tracking shots I’ve ever seen—a three minute run through Central Park in the snow. The music that accompanies this shot is stunning, and amounts to what could be considered an overture, setting musical themes and motifs that will continue to build throughout the film.

I asked my friend, and wonderful composer, Tim Jones to dissect this overture for me:

We then get tutti strings (full-section) playing a sort of halting, interrupted melody. Finally, the violins come in as a section and give us a nice, flowing statement. The horns come in triads, playing a sort of hunting call. The phrase culminates with low brass punctuation (trombones, tuba). Underneath the horn figures are pizzicato strings plucking arpeggios.

The trumpets make their first appearance with a very chromatic, sinewy line that plays in and out of the harmony. I notice the timpani has actually been hiding out behind the gran casa. It swells with rolls on the crescendos. The timpani then really comes to the forefront. This section is basses, gran casa and timpani in a complex, rhythmic interplay. The pizz strings start a figure in the violins.

All of this is very indicative of the beginnings of a life, the start of the heartbeat. Harp and piano appear for the first time. We’re back to the simplicity of the beginning orchestration, but this time with piano added to the colour. Then there is a synth sine wave. This is a very interesting choice, because this is the simplest, most pure form of sound that we hear.

If you were to think of the ‘birth’ of sound, the sine wave is a ‘single cell’ organism. It is a simple, building block upon which much sound is constructed (in nature and electronics).”

This prologue, or overture, is in many ways analogous to the life of a man—the music starts out with a very simple, childlike pattern, which becomes increasingly complex, even as the shot itself remains constant: we remain at the same distance from the man, as he continues to run. One could think of the music as the way our thoughts build upon one another in complexity, and yet, like the faceless figure in the snow, we’re all headed towards the same place—certain death. The first cut comes, and we see the man from a distance, descending towards us, down a path in Central Park, as the camera tracks backwards away from him.

He comes to a halt, in a dark underpass, and then collapses, dead of a heart attack.

This is followed by a shot of a baby being born underwater and emerging to take his first breath.

The narrative then moves ahead ten years. The plot of the movie proceeds as follows: Anna, played by Nicole Kidman, still grieves the loss of her husband Sean, but finally agrees to marry another man, Joseph. Shortly after their engagement party, a ten-year-old boy  shows up and claims to be her dead husband. She gradually comes to believe that the boy is indeed her husband Sean’s reincarnation.

shows up and claims to be her dead husband. She gradually comes to believe that the boy is indeed her husband Sean’s reincarnation.

That’s really all the plot one needs to know, because the plot is not what’s relevant about the movie. It’s instead about the symbols of love, the symbols of loss, and the nature of projection. It uses images to suggest ideas, and it doesn’t try to tie up its loose ends. Is the boy really inhabited by the soul of her dead husband, or is he simply responding to the emotional confusion of Anna? Does it matter? In any case, Anna has a choice to make about the future, and her refusal to let go of the past causes her great suffering.

Dennis Cozzalio wrote the following about Birth on his blog:

I am struck by two very powerful sequences in Birth that I always show to my students when I’m teaching. In the first, Joseph and the boy’s father insist to the boy that he promise not to see or bother Anna again. The boy adamantly refuses. Anna also then tells him, quite forcefully, that she doesn’t want him to bother her again. As she starts to walk away from him, she looks back and sees the boy collapse. This unnerves her, as it is reminiscent of her husband’s collapse in the park.

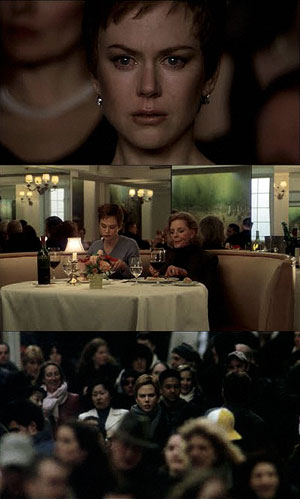

This is followed by a four-minute shot of Anna arriving at the opera and falling deep into her thoughts about what she has just witnessed. It’s as though we can witness her every changing thought—Nicole Kidman is just wonderful in this sequence.

Her look back over her shoulder to the boy evokes the Orpheus myth. The music that plays is Wagner, and as Robert Cumbow points out in his essay on Birth:

The second sequence that has great meaning for me takes place shortly after. The boy calls and leaves a message for Anna on an answering machine in the family apartment, telling Anna to meet him in the park, that she’ll know where. The camera  slowly dollies into Anna’s mother Eleanor, played by Lauren Bacall, as she listens to the message.

slowly dollies into Anna’s mother Eleanor, played by Lauren Bacall, as she listens to the message.

This cuts to a locked-off shot of Anna and Eleanor eating lunch, the sound of their silverware clanking against the plates, as the mother relays the message. The shot is perfectly still, but the music is building in intensity, reflecting Anna’s emotional response to the boy’s message, though she betrays no sense of this emotion in her demeanour.

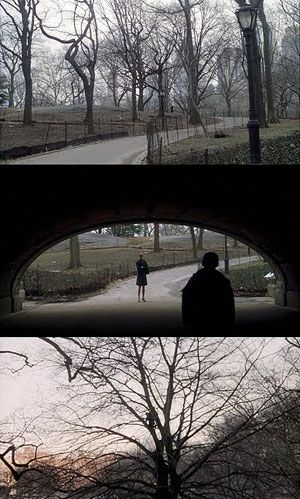

This cuts to a shot of her running down the sidewalk of a Manhattan street, as the music opens up in a romantic and dramatic reprise of the theme established in the overture.

Then we cut to Anna standing immobile at the edge of the park, as the childlike quality of the initial musical theme recurs—suggesting her thought process–perhaps she’s thinking, “…but he’s just a child.”

Then the power of the lower chords starts to emerge again, as she slowly moves forward, with determination and hope, retracing her dead husband’s run down the Central Park path. She approaches the underpass where he died, and the boy emerges from the shadows to meet her.

It’s a wrenching and moving sequence. The music is used beautifully to illustrate the expanse of Anna’s emotions. It tracks the psychological line of the story as well as any film score I’ve ever heard.

The slow dolly into Eleanor, as she listens to the phone message, reflects her fear and puzzlement. This shot also moves me because, every time Eleanor appears, there’s the implication that her own death is on her mind. There was a wonderful exchange between the mother and the boy in the shooting script, which was ultimately cut out of the film, but which nevertheless informs Lauren Bacall’s performance:

What’s it like to be dead? (pause) There’s just that little thing in the back of my head that’s just a little bit worried. And it says I hope I’m ready for this. I hope I’m prepared. So if there is something I should know then I want you to tell me right now. Anything. Doesn’t matter. Or is there nothing to worry about?

SEAN:

I’m a liar.

ELEANOR:

Pretend.

SEAN:

Once I died, I couldn’t see anything. I didn’t hear anything. I didn’t feel anything. And that was it. It was over.

ELEANOR:

Then how did you end up here again?

SEAN:

I don’t know. I just did.

Richard Armstrong, in another excellent article about Birth, writes,

Among many other interesting references and comparisons, Armstrong’s commentary  points out how the feeling of the film is more important than the specifics of the plot. He suggests some of the early images in Birth are reminiscent of a séance.

points out how the feeling of the film is more important than the specifics of the plot. He suggests some of the early images in Birth are reminiscent of a séance.

Jonathan Glazer himself has suggested that its mystical aura has all the makings of a fairy tale. Central Park feels like an enchanted wood; Clara (played by Anne Heche, in a terrific performance) seems almost like a wicked step-sister (her hands are dirty; and she and her husband are distinctly working-class, contrasted with the elite world of Anna’s family and friends); at the climax of the film the boy retreats into a tree, often a symbol of transformation in mythology and fairy tales. When he comes down out of the tree, the spell seems to be broken.

Cumbow describes the influences of Kubrick on the film,

Alternatively, Jim Emerson compares Birth to Bunuel, and particularly to Un Chien Andalou (1929). His analysis is very insightful and he positions Birth firmly in the surrealist tradition. He also summarizes the film very elegantly:

Perhaps this film affects me so much because it feels so personal to me. In 1988 my first significant other died, when he and I were both 32. It was a shattering loss for me and completely upended my sense of reality. For a very long time, my grief enveloped  everything and coloured the way I looked at the world. Years passed before the wound could heal–grief takes a long time to transform, to give birth to something else.

everything and coloured the way I looked at the world. Years passed before the wound could heal–grief takes a long time to transform, to give birth to something else.

The wonder of Birth is that it so vividly captures that experience, from its wintry landscapes to its subtle use of sound (e.g. the quiet laughter one hears as Joseph watches a graveside service from a distance; the distant drones of city life giving way to utter silence and then to one specific sound, which evokes a specific memory—a passing jogger, the sound of the footsteps exaggerated; and the echoes of the large rooms in which so much of the action plays out).

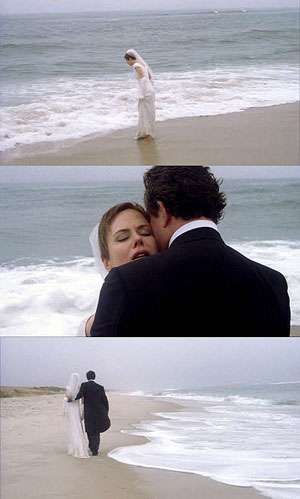

The final scene, where Anna cries at the edge of the ocean in her wedding dress, is powerful because it’s as though she stands at the edge of consciousness, looking out at where she cannot go—her first husband is finally, completely lost to her. Her only choice is to return to life, regardless of how difficult that might be. She and her new husband walk away from the ocean and the viewer is left to ponder what will become of them.

The film ultimately reminds me of Rilke’s poem Requiem For A Friend [5], which meant a great deal to me during my own grieving process:

Only you return; brush past me, loiter, try to knock against something, so that the sound reveals your presence. Oh don’t take from me what I am slowly learning…

If you are still here with me, if in this darkness there is still some place where your spirit resonates on the shallow sound waves stirred up by my voice: hear me: help me. We can so easily slip back from what we have struggled to attain, abruptly, into a life we never wanted; can find that we are trapped, as in a dream, and die there, without ever waking up.

This can occur. Anyone who has lifted his blood into a years-long work may find that he can’t sustain it, the force of gravity is irresistible, and it falls back, worthless. For somewhere there is an ancient enmity between our daily life and the great work.

Help me, in saying it, to understand it.

Do not return. If you can bear to, stay dead with the dead. The dead have their own tasks. But help me, if you can without distraction, as what is farthest sometimes helps: in me.

SOURCES:

1. Dennis Cozzalio, The Mystery of Birth (2006) Sergio Leone and the Infield Fly Rule

2. Robert C. Cumbow, Why Is This Film Called “Birth”?, (2008) Parallax View

3. Richard Armstrong, Love, Death and Birth (2008), Flickhead

4. Jim Emerson, ‘Birth’ of a Buñuelian Notion (2006), Jim Emerson’s Scanners: Blog

5. Rainer Maria Rilke, Requiem For a Friend (1909), ParaTheatrical

Norman Buckley

Norman is a television director and editor known for his work on shows such as Pretty Little Liars, Gossip Girl, The Lying Game, Melrose Place, 90210, Chuck and The OC. He currently teaches part-time at UCLA, in addition to editing and directing.

You can find more of Norman’s work at his website and blog, and he’s on Twitter too – @norbuck.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA