Chinatown

Paramount Pictures

Original release: June 20th, 1974

Running time: 131 minutes

Director: Roman Polanski

Writer: Robert Towne

Composer: Jerry Goldsmith

Cast: Jack Nicholson, Faye Dunaway, John Huston

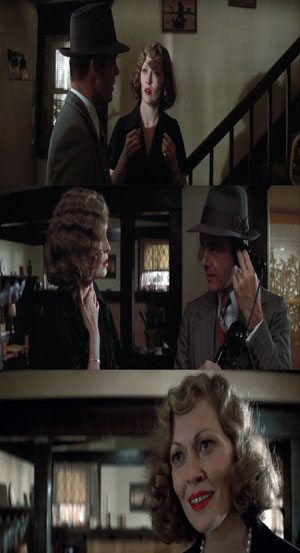

She’s my daughter 01:47:11 to 01:53:57

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

“Forget it, Jake. It’s Chinatown.”

In a world full of possibilities, they say there are only a finite amount of stories and throughout human history we’ve told and retold them countless times. Such is the nature of stories. However, it’s how we choose to tell them that makes all the difference and that’s a gift only a finite amount of storytellers have.

Looking at Chinatown, on the surface, it’s a fairly straight-forward neo-noir detective story. It bears the hallmarks we’ve come to recognise from this genre with films such as Double Indemnity (1944), The Big Sleep (1946) and Sunset boulevard (1950). There’s the male protagonist on some kind of investigative journey that drives the story’s plot – and there’s the woman he encounters along the way who can either be a victim caught up in something she can’t escape, or a femme fatale – or even both.

Yet Chinatown is something much more than that and can’t easily be summarised or categorised in these terms. We have to look further beyond cinema in order to do that; we have to look at its cultural and historical backdrop and how it reflected both the time it was made and the time it was set in.

Set in Los Angeles in 1937, it’s a multi-layered story that’s part mystery and part psychological drama. Inspired by the California Water Wars in southern California over land and water rights which went on from the 1910s through to the 1920s, it sees Jack Nicholson playing Jake Gittes, a private investigator hired by a mysterious woman named Evelyn Mulwray to surveil her husband, Hollis Mulwray, the chief engineer for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

It turns out Hollis has been having an affair and the photos Jake takes during the surveillance end up as front page news the next day. It damages Hollis’ career and undermines his credibility in his opposition to the construction of a new dam on grounds of safety. Then the real Evelyn Mulwray (Faye Dunaway) turns up and we realise Jake’s been used in a political game to bring down an opponent.

Evelyn hires him to find out who the woman was who hired in the first place. As Jake arrives at the reservoir to talk to Hollis he’s confronted with a fresh crime scene and informed by police the chief engineer’s body’s just been found. As his investigation continues, Jake starts to see a larger conspiracy unfolding, one that has little at all to do with conserving water for city taxpayers and everything to do with a plan to incorporate the Northwest Valley into the City of Los Angeles, then irrigate and develop it.

While pursuing this line of investigation, Jake and Evelyn end up giving in to their mutual attractions but there’s something she not been completely honest about. The final revelation in this gritty story, together with its climax, is what lifts Chinatown above its film noir confines and onto another plateau. We see Jake finding a vital clue in his investigation – the glass in the pond belonged to Evelyn’s late husband and he concedes she drowned him there out of jealousy over his affair with the “girl bearing witness to the murder. With this in mind he races to Evelyn’s house to confront her, but he finds her flustered and packing – a clear sign of her guilt and intent to flee the law. After hinting she’ll need an expensive lawyer and that she can afford one, Evelyn becomes angry and wants to know what his visit is about.

Jake takes the handkerchief out of his breast pocket — unfolds it on a coffee table, revealing the bifocal glasses, one lens still intact. Evelyn stares at them.

I found these in your backyard in the pond. They belonged to your husband, didn’t they? Didn’t they?

EVELYN:

I don’t know. I mean yes, probably.

JAKE:

Yes positively. That’s where he was drowned…

EVELYN:

What?!

JAKE:

There’s no time for you to be shocked by the truth. The coroner’s report proves that he had salt water in his lungs when he was killed. Just take my word for it. Now I want to know how it happened and why. I want to know before Escobar gets here because I want to hang onto my license.

EVELYN:

I don’t know what you’re talking about. This is the most insane…the craziest thing I ever…

Jake goes on to try and grind a confession out of her, but he also wants to know about the girl and whether or not Evelyn paid her off because she didn’t have the stomach to  kill her too. Jake’s getting angry and he wants the truth, but is he ready for it? “Who is she? And don’t give me that crap about it being your sister because you don’t have a sister” he demands.

kill her too. Jake’s getting angry and he wants the truth, but is he ready for it? “Who is she? And don’t give me that crap about it being your sister because you don’t have a sister” he demands.

She’s my daughter.

Jake stares at with blind rage and then hits her square in the face, but she doesn’t back away, she just stares right back through her tears, not even defending herself from another potential blow.

I said I want the truth!

EVELYN:

She’s my sister.

Jake slaps her again.

She’s my daughter.

Another slap.

My sister, my daughter

Another two slap.

I said I want the truth.

He slaps her two more times, knocking her back on the sofa and breaking a vase.

She’s my sister and my daughter! My father and I – understand? Or is it too tough for you?

After wanting the truth so badly, Jake is now dumbfounded by it. Evelyn can barely look him in the eye anymore; she’s so ashamed of what she’s finally revealed to him. These are the moments that make stories unforgettable and cinema compelling.

not have been made, however, until the 1970’s when the civil rights movement, Watergate, and the Vietnam Wake woke America up to the depth of its corruption and the nation realised that indeed the rich were getting away with murder … and much more. ¹

not have been made, however, until the 1970’s when the civil rights movement, Watergate, and the Vietnam Wake woke America up to the depth of its corruption and the nation realised that indeed the rich were getting away with murder … and much more. ¹For all its grittiness though, Chinatown is beautiful. Polanski’s expert direction keeps the film well paced and though it’s quite long, there isn’t a shot wasted or a scene under-performed by Nicholson or Dunaway.

Jerry Goldsmith’s sumptuous score is also unforgettable. Written in just ten days after another musician’s score was rejected, Goldsmith’s pieces consist of strings, four pianos, four harps, guiro, and a solo trumpet that employ an advanced harmonic language and avant-garde performance techniques. The opening theme, simply called Love Theme From Chinatown, is a 1930s inspired piece featuring trumpet-player Uan Rasey and evokes a feeling of both a bygone era and a man haunted by his past. It instantly sets the mood for what’s to come in the next two hours.

As a film that rewrote the genre, Chinatown was also where the so-called ‘down-endings’ began, but few have managed it as effectively as this one has.

- McKee, R Story (1999), Methuen ¹

Chinatown gives us the experience we’ve been promised but not in the way we expected it and this is why it remains such a masterpiece. The crucial human values that are explored in each genre like love/hate, peace/war, justice/injustice, achievement/failure and good/evil are ageless themes that have always inspired stories.

To keep them alive and relevant for contemporary audiences they’re re-worked and re-told, but Chinatown is one of those rare films that continues to be re-experienced in each new decade because there’s so much to connect with and on so many levels, and like McKee says, “each new generation finds itself mirrored in the story.”

Patrick Samuel

The founder of Static Mass Emporium and one of its Editors in Chief is an emerging artist with a philosophy degree, working primarily with pastels and graphite pencils, but he also enjoys experimenting with water colours, acrylics, glass and oil paints.

Being on the autistic spectrum with Asperger’s Syndrome, he is stimulated by bold, contrasting colours, intricate details, multiple textures, and varying shades of light and dark. Patrick's work extends to sound and video, and when not drawing or painting, he can be found working on projects he shares online with his followers.

Patrick returned to drawing and painting after a prolonged break in December 2016 as part of his daily art therapy, and is now making the transition to being a full-time artist. As a spokesperson for autism awareness, he also gives talks and presentations on the benefits of creative therapy.

Static Mass is where he lives his passion for film and writing about it. A fan of film classics, documentaries and science fiction, Patrick prefers films with an impeccable way of storytelling that reflect on the human condition.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA