Blade Runner

Warner Brothers

Release date: September 9th, 1982

Certificate: 15

Running time: 117 minutes

Director: Ridley Scott

Writers: Hampton Fancher, David Webb Peoples, Philip K Dick

Composer: Vangelis

Cast: Harrison Ford, Sean Young, Rutger Hauer, Edward James Olmos, Daryl Hannah

Roy’s death: 1:07:00 to 1:15:00

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

The times that we live in are uncertain at best. Whether the turmoil is environmental, political, or economical, we can turn on any rolling news channel and watch cruelty, dismissal and exploitation. Is it human if we feel bad for what we’ve seen, or is it, for better or worse, more human to knuckle down, ignore the larger problems at hand and concentrate on making our own world’s better?

Set in 2019, the world of Blade Runner is edging ever closer. Splicing together sci-fi, action and film noir into a speculative dystopian future, Harrison Ford plays Rick Deckard, an ex-Replicant hunter. Replicants are hi-tech humanoid robots, superior in strength but lacking an emotional depth, with a life-expectancy of only four years lest they learn to love like the rest of us.

After a mutiny in an off-world colony, six replicants have snuck back onto Earth. If they are detected as Replicants, they will be ‘retired’. Like a hired gun from the old West, Deckard is pulled back into the fray he sought to escape for one last job. The climax of Blade Runner, and the scene I will examine here, is a showdown between Deckard and the ‘leader’ of the Replicant band, and last man standing, Roy Batty (Rutger Hauer).

After fighting in eye-designer J F Sebastian’s house, and coming off badly, Deckard tries to escape. Bleeding, his dislocated fingers bound by rags, he scales the wall, and breaks his way out onto the roof. Roy, bleeding after a crack around the head, follows him, commenting,

Roy is challenging Deckard’s human superiority by suggesting that his irrational act will not pay off in the duration of the fight. By calling Deckard “unsportsmanlike”, he is showing us that humans are not above behaving badly, and that they should still be held up to the same standards that they preach.

Deckard, unable or unwilling to face Roy, attempts to jump over to the adjacent building. He misses, and clings to a protruding steel girder for his life, his battered hand slipping on the soaked and rusting metal.

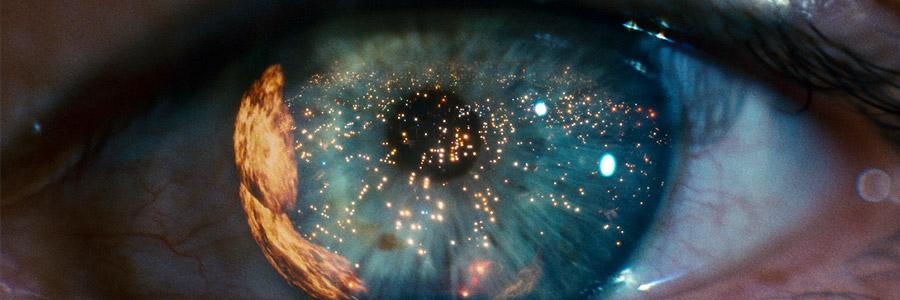

The rain falls as Roy’s figure looms in front of the industrial backdrop. Huge fans are whirring, anonymous pipes creak and light from passing air-traffic pans across the screen. Roy is Deckard’s visual opposite. Whilst Deckard is dark and cowed, Roy is bathed in light, stripped to his pale skin, his white-blond hair slicked back to show his piercing blue eyes. He stands strong, the camera below his feet to give us an impression of his strength, and his superiority over Deckard, illustrating how the tables have turned:

Marilyn Gwaltney comments in her essay Androids as a Device for Reflection on Personhood,

And yet, despite being made from human tissue, and having free will, and definitely being alive, Replicants are not protected by rights; they are considered by their creators as functional objects.

As Gwaltney goes on to say,

Self-actualisation, at the top of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs, is the one thing that Replicants are denied. Due to their limited lifespan, they are never given the scope to realise their full potential as people.

Scott Bukatman states that there is,

Deckard loses his grip from on hand, and dangles storey’s above street level. Roy smiles as he watches, peering down, unblinking. It seems as though Roy is going to be able to bathe in all of the resulting schadenfreude, as Deckard slips further, until he is no longer able to hold on.

Roy grabs him by the wrist at the last second, pulling him up, well clear of danger and onto the safety of the roof.

In saving the man who has killed his closest friends in a concerted effort to kill himself, Roy displays a huge depth of empathy. Knowing that his life is almost at it’s end, he cannot let Deckard die too.

Roy is holding a white dove as he let’s Deckard go. He speaks to Deckard, saying,

The dove flies away, ascending into the sky, as Deckard watches Roy bow his head, and then remain still.

Roy’s death is loaded with symbolism. Whislt fighting in Sebastian’s house, his hand seizes up. He takes a nail, and pierces his palm. He is a vision of Christ on the crucifix, and goes on to bleed from the temple. Roy is rejected as being human, as an ‘other’, something different and destined to be feared and abused. And yet, in his final moments he shows more humanity than any of the ‘human’ characters in the film. Roy’s final act is to save the life of his enemy, the same man who has been trying to capture and kill him, the same man who has killed his friends.

Roy’s reaction towards Deckard is understandable; how many other films centre on a man exacting revenge or home-cooked justice upon the murder of his friends or family? It also seems like a very human reaction, further questioning the so-called divide between the humans and the androids they have created.

- Gwaltney, M Retrofitting Blade Runner (1991), Wisconsin Press

- Bukatman, S, Blade Runner (1997), British Film Institute

A white dove traditionally symbolises innocence and purity, and with Roy, it could be a metaphorical manifestation of his soul. In another biblical reference, Roy is a Noah-like figure, standing in the rain, releasing the dove to find a new home, no longer confined to the ‘ark’ of LA. In the preceding scene, suffering with his hand seizing up, Roy pierces his palm with a nail, visually bearing echoes of Christ’s crucifixion, furthering the religious imagery used with Roy.

Blade Runner deliberately provokes some tough thinking on the behalf of the audience. It is up to us to draw the line between “personhood” and humanity, and then face the consequences. Scott presents us with Roy, a character in whom we can empathise and sympathise with, much more so than the human Deckard. We root for the ‘inferior’ man, and in doing so discover something about ourselves, and learn to be kinder and more accepting of others.

Frances Taylor

Frances likes words and pictures, regardless of media. She finds great comfort and escape in film, and is attracted to anything character-driven with a strong story. Through these stories, she will find meaning in the world. Three movies that Frances thinks are really good for this are You and Me and Everyone We Know (Miranda July), I’m A Cyborg, But That’s OK (Chan-Wook Park), and How I Ended This Summer (Alexei Popogrebsky).

When Frances grows up, she would like to write words and make pictures and have cool people recognise her on the street and tell her that they really enjoy her work.

She can be found overreacting and over-caffeinated on Twitter @penny_face, a childhood moniker from her grandmother owing to her gloriously round face.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA