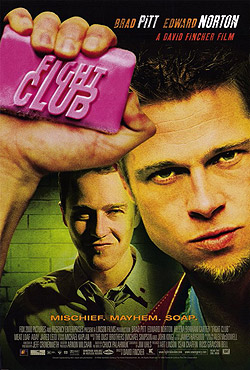

Fight Club

20th Century Fox

Original release: October 15th, 1999

Running time: 139 minutes

Director: David Fincher

Writer: Jim Uhls

Music: Dust Brothers

Cast: Brad Pitt, Edward Norton, Helena Bonham Carter

In death, a member of Project Mayhem has a name: 1:40:55 to 1:43:40

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

I rarely feel as much of an outcast in my understanding of a film as I do with Fight Club. It hasn’t always been like this though; I saw the movie for the first time in 1999 when it was first released. At the age of 20, I was with the flock, almost an adult but not quite. On my way out of the cinema after seeing the film, I just wanted to rage against the machine.

I felt that Fight Club carried a meaningful message about the way we lived our lives in the beginning of the third millennium and I looked to the character of Tyler Durden, played by Brad Pitt, as a mentor figure of great wisdom. It took me a while before I began to look at it differently – very differently – and it is baffling to me now that I had not been able to see this blatant angle before.

Even more baffling though, I have not yet found much discussed on the subject of religion in a meaningful way in the context of the film. One reason for this is possibly a general lack of theological enquiry in cinema, elaborated on by Christopher Deacy:

And later he says to further this point:

Fight Club is not short of academic analysis exploring many issues including gender roles, feminisation of America and the male fascism of Project Mayhem as a response to that, nihilism, self-discovery and of course the big bogeyman, consumerism. Some have talked about Tyler Durden’s character as spiritual leader and a Christ figure which seem to edge towards the domain of religion, but it isn’t satisfying enough since it’s missing the point entirely when we really look at what’s unfolding before our eyes upon viewing Fight Club.

The Narrator played by Edward Norton is often said to represent the “everyman” and if that was in fact the case humanity would be in big trouble indeed. With a seemingly normal life, home and job, the Narrator is desperately in need of something. He isn’t quite sure what it is, but to us – the audience – it soon becomes clear that he wants to belong to a community of some sort. Well, pretty much any sort as far as he is concerned.

He begins to attend various support groups, among them is a group for testicular cancer victims. While pretending to be a victim himself, he tells us why he is there; already indicating his desire to form something that is more than just a group; a community of spiritual proportions:

Some of this sounds familiar somehow; it could be from that little book called the Bible. It is this point when the Narrator first encounters the charismatic soap salesman Tyler Durden (Brad Pitt). Together they agree that there is a problem with the world and that the problem isn’t them. Shortly after they begin to fight frequently in public places for no apparent reason; a practice that will be repeated over and over again from then on to become what I could only describe as a ritual. In the beginning this ritual is what helps to attract people to a quickly growing community that is soon referred to as Fight Club. Later on the fights will serve to maintain a bond between members reminiscent of other forms ritualistic behaviours like praying in a particular direction or ingesting pieces of wafer. Tyler is now the leader of a group of aggressive men taking their misplaced anger and frustration and putting it in one specific direction: consumer culture. He is certainly a born leader; his speeches to the group are effective, motivating and infuriating:

Working jobs we hate so we can buy shit we don’t need.

We are the middle children of history man,

No purpose or place.

We have no great war.

No Great Depression.

Our great war is a spiritual war.

Our Great Depression is our lives.

We’ve all been raised on television to believe

That one day we’d be millionaires and movie gods and rock stars.

But we won’t.

And we’re slowly learning that fact.

And we are very, very pissed off.”

Members are hanging on Tyler’s every word as we begin to recognise something we’ve already seen many times in human history: a preacher and his flock. This is the unique angle this film has to offer if we care enough to see it: an insightful and realistic depiction of how religion is born. And this study is vital to our understanding of religion as a whole, but Christopher Hitchens makes this point much more eloquently (and bluntly) than I can:

Fight Club allows us to sit back and watch the process of religion in its formation; a modern day religious sect with modern day ideas but just as primitive and sinister in its fundamentals as many religions that have been around for centuries.

As Tyler becomes increasingly aware that he has full control over his flock, he creates Project Mayhem; a new activity for members with ‘homework assignments’. The assignments come in sealed envelopes, different instructions for different members. The members are full fledged followers at this point; their willingness to take a sealed envelope with orders without knowing what those orders are remind me of the determination and fanaticism of the suicide bomber of our time.

This is when the film comes to the scene that I chose to discuss in greater detail here. Fight Club has now effectively evolved into Project Mayhem with its busy headquarters, hierarchy and administration. And then, just like that, Tyler Durden is gone. It’s obvious that Project Mayhem is fully functional without him as the Narrator wanders around being largely ignored by everyone. (In the interest of context, the members of Project Mayhem are evidently aware that the Narrator has a split personality and also know that the Narrator is in control of his own body at this point).

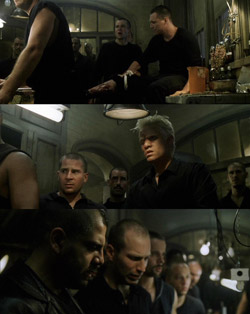

After a ‘homework assignment’ gone wrong, a group of members come back to the headquarters with the corpse of Bob (Meat Loaf); a friend of the Narrator from the testicular cancer group who had been fatally shot by a police officer.

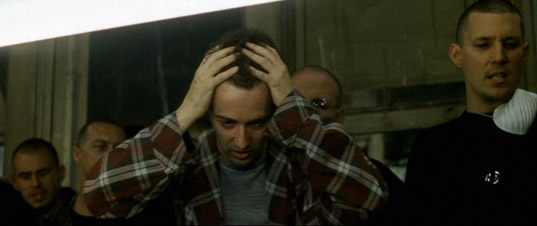

The Narrator has his doubts about Fight Club and Project Mayhem as he is losing control of the events around him. He feels the weight and the seriousness of the situation but he is the only one. The others around him have lost understanding of the value of human life as a result of several months’ of systematic brainwashing. A prominent member, played by Jared Leto, who is a sort of deputy leader in Tyler’s absence orders Bob to be buried in order to hide evidence of what has happened.

In response to the Narrator’s outrage and calling Bob by his name, a member reminds him that “in Project Mayhem we have no names” – another one of the Tyler-imposed rules. The Narrator naively persists in a vain attempt to bring the people around him back to sanity by repeating Bob’s full name this time:

And then; something amazing happens. A member who has no authority of his own in the Fight Club hierarchy begins to speak:

And then he repeats:

Gradually, one after another the others join in what soon becomes loud and uncompromising religious chanting of the line that symbolises the latest rule of Fight Club. I think this is the most pivotal moment in the film. The void in the absence of the leader is immediately filled by someone – quite randomly, due to a misunderstanding – and a new rule is embraced by the entire group as soon as it is created.

There is no process or critical thinking involved, the rule is there and it is there to stay because somebody said so. This is when religion is truly born, not when a founder establishes its principles but when religion begins to function without its founder; randomly, often in multiple directions all at once, completely out of control.

Looking at this new rule a little bit closer helps us to understand how such groups often take unexpected directions. The random gospel they just created is already at odds with the founder as it implies individuality as a positive entity that is rewarded to members upon death. Tyler would disagree; he seems to profess that giving up individuality is the way to enlightenment and it isn’t something members should want back before or after death.

This shows that the foundational principles or the original intentions of the founder of any given religion cannot be maintained as the group’s own survival will always take priority after the messiah is gone.

In the absence of founders, let that be Tyler Durden, Jesus Christ, the prophet Muhammad, L. Ron Hubbard or Joseph Smith, they become sacred symbols for their flock, but whether these groups can live by the ethical essence and principles laid down at their formation is highly questionable. The scene brilliantly shows that debating the lives and the ideas of founders of religious groups is quite irrelevant if we try to understand religion itself.

As it often seems to be the motivation behind the leadership actions of religious groups, the rule in the scene is created for the convenience of what is now an increasingly complex organisation putting its own survival before any of its principles.

A live Intelligence Squared debate took place on the 19th of October 2009 in London’s Methodist Central Hall with the theme “The Catholic Church is a force for good in the world”. Arguing for the motion were Archbishop John Onaiyekan and former Conservative MP Ann Widdecombe; while Stephen Fry with Christopher Hitchens – both well-known for being critical of religious groups – were debating on the opposite side. In this debate Fry raised contradictions between the Church and its founder:

The separation between religion and its founder is something we need to look at with an open mind and honesty when measuring the value of religion in a modern world that has an infinite capacity for change and re-evaluation. The scene in question allows us to witness the very moment the two part from one another. While I believe that this scene has academic significance worthy of scrutiny, it also had a great personal impact on me. This is the scene where the Narrator finally comes to his senses and turns against Fight Club, but this is also the scene where I came to my senses and finally started to see what this film is really about.

Fight Club is a very complex and clever film that warrants discussion on many different subjects, but I think that the birth of religion should be seen as its most important overall theme. Having seen it a fair number of times, the eventual realisation of this theme was a very humbling experience. I’ve always been quite critical of religious groups; it is innate with me, I have always felt cautious about people who claimed unproven or unprovable things with absolute certainty.

That lack of humility facing the unknown always made me feel uneasy. This was the very state of mind of a sceptic that I had at the age of 20 when walked in the cinema to see Fight Club. And yet when I walked out at the end of the film, I was a Fight Club convert; ready to rage against the machine.

- [1] Mitchell, Jolyon; Plate, S. Brent The Religion and Film Reader (2007), Routledge Taylor & Francis Group

- [2] Hitchens, Christopher God is not Great (2007), Atlantic Books

- [3] Transcript of the Intelligence Squared Debate

Realising that Fight Club is about religion at its core changed the way I look at a lot of things. I was quite shocked to see that I was so wrong on such a massive scale and my intellectual submission to a religious sect forced me to improve on my critical thinking a great deal. Of course, Fight Club is just a film, I was never actually a member of any sect in real life, but my mind responded to what I saw on the screen and that’s more than enough to feel some degree of humility.

I learned that religion can potentially evolve to incorporate contemporary ideas with a broader appeal than ancient texts – ideas that can appeal to anyone – but when you realise that a group tries to exercise excessive control over what you do and what you think, it is time to leave to room.

Arpad Lukacs

Arpad is a Film Studies graduate and passionate photographer (he picked up the camera and started taking stills just as he began his studies of moving pictures). He admires directors that can tell a story first of all in images. More or less inevitably, Brian De Palma has become Aprad’s favourite filmmaker.

Then there’s Arpad’s interest in anime. He was just a boy when he saw Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind on an old VHS and was hypnotised by the story of friendship, devotion and sacrifice. He still marvels at the uncompromising and courageous storytelling in Japanese anime, and wonders about the western audience with its ever growing appetite for “Japanemation”.

Have a look at Arpad's photography site, and you can follow him on Twitter @arpadlukacs.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA