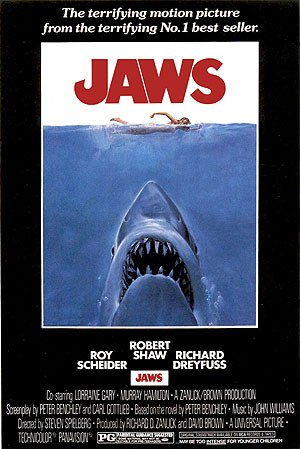

Jaws

Universal Pictures

Original release: June 20, 1975

Running time: 124 minutes

Director: Steven Spielberg

Writers: Peter Benchley, Carl Gottlieb

Composer: John Williams

Cast: Roy Scheider, Richard Dreyfuss, Lorraine Gary

Opening scene: 00:00:00 00:05:10

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

The great fish moved silently through the night water, propelled by short sweeps of its crescent tail. The mouth was open just enough to permit a rush of water over the gills. There was little other motion: an occasional correction of the apparently aimless course by the slight raising or lowering of a pectoral fin as a bird changes direction by dipping one wing and lifting the other. The eyes were sightless in the black, and the other senses transmitted nothing extraordinary to the small, primitive brain. ~ Peter Benchley, Jaws

As a kid growing up on a small island, a drive to the ocean was only ever an hour away in either direction. I’d spend hours under the parasol building sandcastles and making sure the tide never got to them, yet somehow in the end they always did. I remember lunches eaten from Styrofoam plates and cans of cola chilled in the ice box, but what I never recall is going into the water.

So effective was Steven Spielberg’s Jaws that it managed to instill in me from a very early age that the ocean was a place where unseen creatures fed on grown-ups.

Based on the novel by Peter Benchley, the story of Jaws takes places in the seaside town of Amity Island in New England. It begins very late at night with a beach party where we see a young guy, Tom Cassidy (Jonathan Filley), smiling at a pretty blonde, Christine Watkins (Susan Backlinie).

He moves closer to her and whispers something we can’t hear. She jumps to her feet and with a smile on her face she leads him past the sand dunes. She looks back to see if he’s following, and sure enough he is.

What’s your name again?

CHRISSIE:

Chrissie

TOM:

Where’re we going?

CHRISSIE:

Swimming!

Running, he stumbles, falls and gets up again. Chrissie sheds her jacket and the rest of her clothes follow while he drunkenly pleads for her to slow down. She doesn’t though, and instead heads into the water.

As the moonlight glistens over the ocean, Chrissie heads out further, disappearing beneath the surface gracefully and re-emerging again. In this shot we see the sunrise beginning to peek over the horizon and the camera lingers as Chrissie hollers at him to get into the water. He’s too drunk though and struggles with his clothes, eventually passing out for the remainder of the night.

Something changes then and we’re no longer watching Chrissie the same way as before. The point of view has changed and so too has the music. It’s that alternating pattern of two notes, E and F, beginning slowly and gradually speeding up, mirroring our own anxieties over what’s about to happen.

We’re now underwater, looking up at Chrissie swimming on the surface, silhouetted against the moonlight. The unseen creature is now moving closer toward her legs which are dangling freely. One sharp pull, followed by another and then another and Chrissie plunges beneath the surface, coming back up with a scream.  She frantically attempts to swim away but is immediately pulled back. Thrashing and screaming as the attack continues, Spielberg then suddenly cuts to Tom blissfully asleep on the shore as the waves laps at his feet.

She frantically attempts to swim away but is immediately pulled back. Thrashing and screaming as the attack continues, Spielberg then suddenly cuts to Tom blissfully asleep on the shore as the waves laps at his feet.

We then return to the attack and Chrissie continues to thrash around. What’s perhaps most terrifying of all is that Spielberg never shows us what’s going on beneath the surface. He leaves that to our imagination. Chrissie breaks free and holds on to a nearby buoy where she’s safe for another couple of seconds before her unseen assailant moves in for the final attack – and then she’s gone.

There’s no thrashing, no screaming and Williams’ score ceases. There’s just the sound of the waves lapping at Tom’s feet as dawn continues to break. The scene is just over five minutes in length, but its impact has lasted a lot longer, with many taking the poster tagline “Don’t Go in the Water” quite literally.

While there are many standout moments in Jaws, such as the simultaneous dolly-in and zoom-out shot that brought us the close-up on of police chief Martin Brody’s (Roy Scheider) face when young Alex Kintner is killed, and when shark expert Matt Hooper (Richard Dreyfuss) examines Chrissie’s remains, it’s really the opening scene which stays with us, haunting us and sometimes even taunting us when we get close to the water.  Williams’ score begins to creep into our minds and those underwater point-of-view shots come into focus.

Williams’ score begins to creep into our minds and those underwater point-of-view shots come into focus.

It was never about thinking I might see a shark or something else in the water that made me stay out of it – it was more the fear that I might not. During this initial attack, Spielberg’s shark remains an off-screen presence and it plays on our fears of the great unknown. In these moments we have no idea how big it is, but we can almost feel its fin brushing past our thighs and that’s more than enough.

Benchley’s novel provided a strong basis for an effective movie thriller that terrified movie audiences, placing Spielberg’s adaptation right at the top alongside Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960) and Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) as one of the scariest films ever made. Yet the opening scene wasn’t originally envisioned this way.

- Benchley, P. Jaws (1974)

- Witchel, C. You Are What You Hear: How Music and Territory Make Us Who We Are (2010), Algora Pub ¹

- Buckland, W. Directed by Steven Spielberg: Poetics of the Contemporary Hollywood Blockbuster (2006), Continuum International Publishing Group Ltd ²

It was Jaws which firmly cemented Spielberg as a director to keep our eyes on. It was the first film to break the $100 million mark at the box office and for two years, until Star Wars in 1977, it was the most successful movie in history, ushering in the age of the summer blockbuster.

Today I live on a different island than the one where I was born and raised, and the ocean is much further than an hour’s drive. It’s been decades since I last sat on the sand with a bucket and spade, but take me back there now and I’m not all that certain how far into the water I’d go – if at all. It’s not what we see that scares us, but what we don’t.

Patrick Samuel

The founder of Static Mass Emporium and one of its Editors in Chief is an emerging artist with a philosophy degree, working primarily with pastels and graphite pencils, but he also enjoys experimenting with water colours, acrylics, glass and oil paints.

Being on the autistic spectrum with Asperger’s Syndrome, he is stimulated by bold, contrasting colours, intricate details, multiple textures, and varying shades of light and dark. Patrick's work extends to sound and video, and when not drawing or painting, he can be found working on projects he shares online with his followers.

Patrick returned to drawing and painting after a prolonged break in December 2016 as part of his daily art therapy, and is now making the transition to being a full-time artist. As a spokesperson for autism awareness, he also gives talks and presentations on the benefits of creative therapy.

Static Mass is where he lives his passion for film and writing about it. A fan of film classics, documentaries and science fiction, Patrick prefers films with an impeccable way of storytelling that reflect on the human condition.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA