The Blair Witch Project

Haxan Films / Artisan Entertainment

Original release: October 22nd 1999

Certificate: R

Running time: 81 minutes

Writers and directors: Daniel Myrick, Eduardo Sánchez

Producer: Robin Cowie Gregg Hale

Composer: Antonio Cora

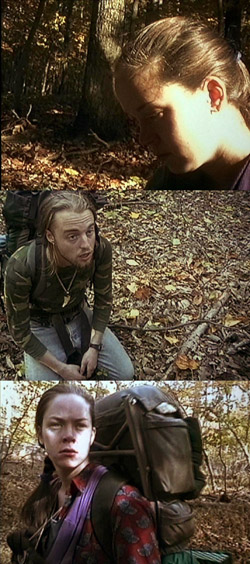

Cast: Heather Donahue, Michael C. Williams and Joshua Leonard

Final scene 01:12:14 to 01:14:14

Deconstructing Cinema: One Scene At A Time, the complete series so far

“Deathly also was the fear struck into the hearts of established movie executives.

Made for nothing, by nobodies and without the benefits of the Hollywood marketing machine, The Blair Witch Project swiftly

became the most profitable film of all time.”

~ Rupert Mellor

The year was 1999. I was twelve years old and having one of my regular weekend sleepovers at the home of my childhood friend. We had spent the best part of the morning riding our bikes around the neighbourhood before wasting the afternoon building an unsuccessful catapult out of optimism, wood and rope. The sun was beginning to set when we retreated indoors to see out the remainder of our time playing flash games on the family computer and listening to the music we had taped off of the local radio station.

When the time came to fall asleep however, the night took a less idyllic turn. As I lay awake in the dark, alone and petrified amongst surroundings that were only slightly familiar, I listened to the walls of the old house creak, to the sound of leafless winter branches scratching on the tin roof, and I prayed that there wouldn’t come a time later in the night when I needed to use the toilet, inconveniently located on the outside of the house.

‘JOSH!’ The voice was familiar, screaming faintly inside my mind, ‘WHERE ARE YOU? TELL ME WHERE YOU ARE JOSH’!

I shut my eyes tight. I had heard this same voice earlier in the evening while listening to the radio and it continued to haunt me into the night. I didn’t know who this Josh person was and it would be many years later before I was brave enough to find out.

The Blair Witch Project had opened in cinemas across America, swiftly dominating the big budgets, special effects technologies and conventional marketing strategies on which the Hollywood studios were so heavily reliant. What my friend and I had stumbled across on that particular evening as we fast-forwarded our way through a tape of the local radio’s Top 100 Hits of the Year was the Blair Witch Remix version of the pre-existing Korn track ‘It’s On’.

By using extracts of dialogue directly lifted from the film, the song functioned as one of many examples of the guerrilla style marketing strategies that saw a low budget independent movie grow into one of the most profitable films of all time.

Although I was yet to see it, I found myself being terrified of the film. In 1998, one year before its release, the film’s directors Daniel Myrick and Eduardo Sánchez established an official website for The Blair Witch Project which provided viewers with weekly updates of unseen footage of the out-takes, diary excerpts, photographs, witness interviews, family statements, ‘official’ looking documentation regarding the missing persons, all perpetuating the faux myth surrounding the infamous Blair Witch.

At the time of the film’s release, the site had received more than 50 million hits and so the film functioned merely as an extension of the Blair Witch mythology. In addition, spin-off sites began perpetuating the story that the events featured in the film were real. This created a sense of ambiguity surrounding both the film’s content and context which was further amplified through the films raw, improvisational representation of a Cinéma vérité style of filmmaking. By replicating the aesthetic style of Cinéma vérité which is a common mode of documentary films, The Blair Witch Project blurred the line between fact and fiction.

So, what made this highly anticipated film, in which the viewer sees very little, successful? While evaluations of cinematic quality remain a notoriously subjective category, critical appraisals of Blair Witch Project tend to turn along two axes; the value of the ‘nothing’ portrayed by the film, and the artistry (or lack thereof) of the film’s production. BWP’s ‘nothing’ is either a source of celebration or a fatal flaw. According to some critics, the film’s circumspection, where its camera seems to capture everything except the source of menace, engages the viewer’s imagination and provokes an emotional response. For example, Atkinson asserts:

Following this argument, it is the speculative quality or the sheer possibility of unknown terror or unseen embodiment that haunts us as we watch the film. It is the omission of providing the source of our fears in its actuality that keeps us at the edge of our seats. As Sarah L. Hingley and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock point out,

Best illustrating the argument of the ‘nothingness’ that terrifies the viewer is the film’s final scene that offers a chilling denouement of the tension that has been built throughout the course of the plot. The film is set in the small country town of Burkittsville, Maryland (formerly Blair), a place where folklore lives through the nonchalant yet curiously cautious attitudes of the local community.

We are introduced to the town, its people and the local folklore through the lens of three students, Heather Donahue, Michael Williams and Joshua Leonard who have arrived in the town to make a film about the most well-known of the local legends, the Blair Witch. After gathering information from the community, the students venture into Black Hill Forest in search of footage but soon find themselves lost. Tension begins to build as the trio become more desperate to escape and their fear is increasingly fuelled by a strange sequence of occurrences. Haunted each night by mysterious sounds coming from outside the tent, the minds of the protagonists become less reliable.

One night amongst the fear and confusion Josh separates from the group but as the days pass by his voice can be heard, calling for his friends at night.

Sigmund Freud’s seminal essay on the Uncanny sheds light on this issue:

Indeed, death, dying and ghosts are a central part of this landmark film. We never witness the witch in flesh, we never visually perceive any demonic or ethereal being, but we remain petrified of the sheer possibility. Within this possibility, this fear of actually looking upon some monstrous, distorted shape and the anticipation of terror, lurks the very effect of uncanniness. The uncanny relies on a gradual build-up of strange phenomena that are subject to rationalization.

For example, when our protagonists hear strange noises in the night and immediately offer rational explanations: It must be some delinquents playing with their heads, or an animal loudly crashing its way through the woods. However, both the protagonists and the spectators are creepily aware that there might be another possibility and within that lies the fear, the realization that creeps up our spine that an unknown phenomenon might exist and that it has no place in our rational world.

Stuck in a repetitive circle with no end in sight, lost, exhausted and unable to find their car, the protagonists slowly yet maddeningly descend into the Twillight Zone made of voodoo dolls, strange ritual circles, noises in the night, endless circles and the petrifying woods, where all could be possible.

- Freud, Sigmund. ‘The Uncanny’. The Standard Edition of the Complete Psychological Works of Sigmund Freud, ed. and trs. James Strachey, vol. XVII (London: Hogarth, 1953), pp. 219-252. Print. [2]

- Higley, Sarah L. and Jeffrey Andrew Weinstock. ‘The Blair Witch Controversies’. Nothing That Is, Ed. By Higley and Weinstock. Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 2004. Print. [1]

- Potton, Ed and Amber Cowan. Into the woods: The Definite Story of the Blair Witch Project. Suffolk: Screen Press Books, 2000. Print.

The value of this open ending can also be read in terms of the fragility of the rational world and positivist sets of beliefs. While the content of The Blair Witch Project provides a number of angles for analysis such as exploiting Western folklore, the monstrous feminine and nature as unpredictable and inexplicable, the theme of the uncanny is the one that has paved the way for the film’s unpredicted success.

Watching the film again, I find myself revisiting the mindset of the twelve year old me. I feel the familiar sensation of dread because despite the fact that I have now seen the movie (many times), the sense of the uncanny as represented in the film means that the mystery of the Blair Witch remains as unsolved in my mind as it did on a sleepless night in 1999.

Tyson James Yates

Tyson Yates has spent most of his life living in Australia which is where he received both a healthy tan and a degree in Communications and Media from Griffith University, Brisbane. Upon graduating Tyson relocated to Edinburgh where he now spends most of his free time trying to keep warm which is a feat that fortunately does not get in the way of watching films.

There are however two things that Tyson loves more than film. One is reading short biographies about himself that are written in the third person and published online. The other is publicly shaming a Hollywood Blockbuster in the company of people who want nothing more than to enjoy it for the mind numbing entertainment that it is. Sound pretentious? Well so is having a thing for reading short biographies about himself that are written in the third person and published online.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA