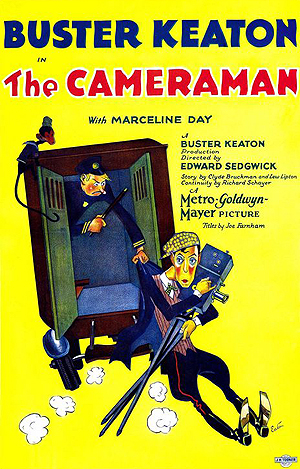

The Cameraman

THE CAMERAMAN (MOVIE)

MGM

Original release: September 22nd, 1928

Running time: 67 minutes

Directors: Edward Sedgwick, Buster Keaton

Writers: Clyde Bruckman, Lew Lipton, Joseph Farnham

Cast: Buster Keaton, Marceline Day, Harold Goodwin

The Cameraman is the last truly great film from Buster Keaton, one of silent cinema’s trailblazers. Like all his best work, it remains as charming as it is hilarious, and it gives us an opportunity to reflect how far, at the time of its making, the medium of film had come in terms of storytelling and technique, due, in part at least, to the artistic and commercial success of people like Keaton.

The story sees, Keaton, as always, trying to win the heart of a pretty girl, this time the secretary at a newsreel production company. Deciding to trade in his tintype camera, he tries to make it in the world of moving pictures, but faces an array of obstacles, including, amongst other things, a jealous rival Cameraman, his own lack of experience, and an interfering monkey.

The plot moves along at a brisk pace, with more than enough of the three vital ingredients for a Buster Keaton movie; firstly, memorable scenes, particularly the trip to the Yankee stadium (“Aren’t the Yankees playing today?” “Sure – in St. Louis”). In the absence of an actual game, Buster simply mimes an imaginary one against himself. Secondly, his trademark brilliant physical comedy, and there are so many to choose from, but my favourite remains Keaton being squeezed into a small changing room with a huge man, largely improvised on the day of shooting. Thirdly, there are the jaw dropping, bone crunching stunts; watch how he loses and regains his seat on the bus next to his date.

A special mention also must go the real co-star of the film, Josephine, an Organ Grinder’s monkey whom Keaton adopts. Apart from providing some vital plot strands, she actually gives an excellent and genuinely funny performance, as full of pathos and well-timed comic moves as any of her human colleagues.

I was lucky enough to see The Cameraman recently on the big screen, as the second half of a double bill with the 1910 silent version of A Christmas Carol. Watching both films back to back provided a fascinating insight into how the language and skills of cinema had progressed in a relatively short space of time, less than two decades. In A Christmas Carol, the camera doesn’t move, as if filmmakers can’t yet get past the idea that film should only ever be a static record of a performance. However, by the time of The Cameraman, it certainly does move, up and down, and in one scene in particular, it follows Keaton, via a split building set, as he runs up and down a long flight of stairs from the roof to the basement in one cut. But, rather than just always being a clever technical gimmick, the movement helps tell the story and at times, by forcing the audience viewpoint, helps set up visual jokes.

The wildly different running times of the two films also demonstrates how the makers of the latter had learned to be unafraid to take time to tell a story. These are all  techniques Keaton had refined and introduced into film, and because of this, I don’t think it is unfounded to call him a cinematic pioneer, along with his comedy contemporaries Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin, who were making similar strides.

techniques Keaton had refined and introduced into film, and because of this, I don’t think it is unfounded to call him a cinematic pioneer, along with his comedy contemporaries Harold Lloyd and Charlie Chaplin, who were making similar strides.

The Cameraman was the first of a three-picture deal with MGM for Keaton. After years working for Joseph Schenk, with a minimum of interference, the expense and poor box office performance of The General had led to strict curbs both on spending and on Keaton’s directorial independence. The new set-up didn’t seem to have any great impact on the making or content of this film, other than the endless product placement for the MGM brand name and some of its product. However, unfortunately, this state of affairs wasn’t to last, as new boss Irving Thalberg seemed unwilling or unable to understand Keaton’s working methods, namely, using the same small crew, and keeping an air of freewheeling spontaneity in the creative process.

The result would see control over the personnel and product wrenched away from Keaton, leading to a steep drop in the quality of his films, and his eventual decline into poverty, obscurity and alcoholism, before his rediscovery in the 1960s, a few years before his death. However, this was all much further down the line, and The Cameraman still gives us “The Great Stone Face” in his prime, risking everything for the girl and the laughs, somehow always keeping both his body and his deadpan expression in one piece.

Simon Powell

Simon grew up on a steady diet of James Bond and Ray Harryhausen films, but has been fascinated with the horror genre since a clandestine viewing of A Nightmare on Elm Street as a teenager. Since then his tastes have expanded to take in classic horror from the Universal and Hammer Studios, as well as branching out into Video Nasties, Sci-Fi, Silent Comedies, Hitchcock and Woody Allen.

Apart from getting married, one of his fondest memories is buying a beer each for both Gunnar “Leatherface” Hansen and Dave “Darth Vader” Prowse at a film festival, and listening to their equally fascinating stories of life at totally different levels of the industry.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA