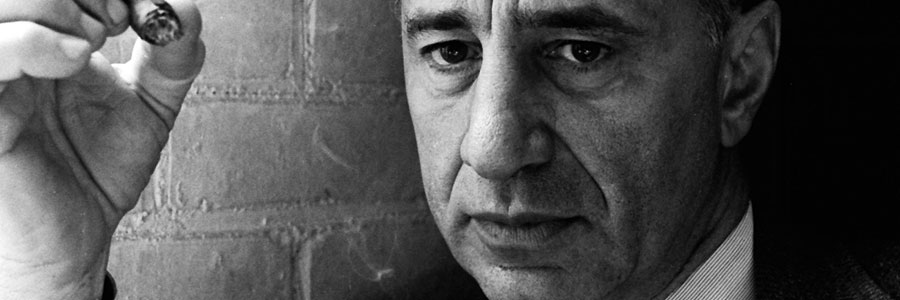

Elia Kazan

It was my mother who introduced me to many of the films I still love today. Her penchant for classics from the 1940s through to the 60s included the sprawling romantic epics and the sizzling melodramas. In between those there was the occasional films that captured the gritty social realism of those eras and featured some of the most amazing actors to have ever graced the screen. This was how I came to know the films of Elia Kazan.

Elia Kazan

Elia KazanBorn to Greek parents in Istanbul on September 7th, 1909, Kazan, along with his family, moved to America when he was four years old. After attending public schools in New York, he enrolled at Williams College in Massachusetts, working various part time jobs to pay his way. In 1932, after spending two years at Yale University School of Drama, he moved back to New York to become a professional stage actor. It’s here that he got in with Group Theater and involved in plays that offered social commentary. But as with many things he experienced before, Kazan found it hard to fit in, but the group showcased many lesser known plays with deep social or political messages, which no doubt held his interests. Of that time, Kazan wrote in his autobiography, America, America:

The Skin of Our Teeth, dir. Elia Kazan, 1942

The Skin of Our Teeth, dir. Elia Kazan, 1942Strasberg, as many would come to know, became director of the non-profit Actors Studio (founded by Kazan, Cheryl Crawford and Robert Lewis in 1947) in 1954 before founding the Lee Strasberg Theatre and Film Institute in 1969 where his teachings were inspired by Russian actor and director Konstantin Stanislavski and his best student Eugene Vakhtangov. Considered to be the father of method acting, Strasberg helped revolutionize the art of acting in American theater and films and trained several generations of actors, including Anne Bancroft, Dustin Hoffman, Montgomery Clift, James Dean, Marilyn Monroe, Julie Harris, Paul Newman, Al Pacino and Robert De Niro, some of whom went on to star in Kazan’s films later on.

A few years later, at the age of 26 and having performed considerably well on stage as an actor, despite Strasberg’s comments, Kazan began directing a number of the Group Theater’s plays, but he’d have to wait until 1942 to achieve his first notable success. This came when he directed the Pulitzer prize-winning play by Thornton Wilder, The Skin of Our Teeth, starring Montgomery Clift and Tallulah Bankhead. From there he went on to direct Death of a Salesman, by Arthur Miller, and Tennessee Williams’ A Streetcar Named Desire, starring Marlon Brando. Further successes in theater directing came with Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, Sweet Bird of Youth, The Dark at the Top of the Stairs and Tea and Sympathy.

A Streetcar Named Desire, dir. Elia Kazan, 1951

A Streetcar Named Desire, dir. Elia Kazan, 1951In 1945, after directing two short films, A Tree Grows in Brooklyn was released, marking Kazan’s debut as a feature film director with a story that gave him the chance to focus his attention on contemporary concerns. In 1947 he directed Gentleman’s Agreement. Starring Gregory Peck and John Garfield, the film tackled a rarely-discussed issue in America, anti-Semitism. For this film, Kazan was awarded his first Oscar as Best Director. Two years later, in 1949, he followed it up with Pinky, a film about a light-skinned, African-American nursing student, played by Jeanne Crain, passing for white. The film went on to be nominated for 3 Academy Awards.

What was becoming clear during this time was that Kazan had a particular talent for dealing with personal alienation and social injustice in his films. This would become most apparent with his next features. After directing Brando in the stage version, he would use him again in the film version of A Streetcar Named Desire. The film sees Vivien Leigh also reprising her stage role as Blanche DuBois, a delusional woman who comes to visit her pregnant sister Stella and meets her brutish husband Stanley Kowalski. While Stella’s at the hospital giving birth, something unspeakable happens to Blanche, but what’s equally shocking is how everyone reacts and what happens when Stella returns home with the baby.

On the Waterfront, dir. Elia Kazan, 1954

On the Waterfront, dir. Elia Kazan, 1954The film received a staggering 12 Oscar nominations, of which it won 4, but it’s here we start to see how censorship was beginning to affect works of social importance with the ending being drastically changed from what Williams had originally intended. Nevertheless, A Streetcar Named Desire remains a true classic in terms of its direction, writing, performances and complex these of sexuality and morality. It was also one of the films I watched a child, but wouldn’t understand until many years later.

Kazan’s 1954 film, On the Waterfront, also starring Brando, was another film dealing with contemporary issues that affected the working class. Its story centers on a former boxer turned longshoreman, Terry Malloy, who struggles to stand up to his corrupt union bosses who are in with the Mob. We learn that Terry could’ve had a promising career as a fighter, had he not been persuaded by his brother Charley “The Gent” (Rod Steiger) to deliberately lose a fight so that his union boss Johnny Friendly (Lee J. Cobb) could win money betting against him.

Terry ends up being responsible for the death of his co-worker Joey Doyle (Ben Wagner) and rather than risk putting himself in danger he remains quiet about what he knows. However, he can’t play deaf and dumb for much longer, especially with Joey’s sister Edie (Eva Marie Saint) and “waterfront priest” Father Barry (Karl Malden) urging him to come forward.

East of Eden, dir. Elia Kazan, 1954

East of Eden, dir. Elia Kazan, 1954The film contains many highlights but its most famous line is delivered when Terry says to his brother “I coulda’ been a contender, instead of a bum, which is what I am – let’s face it, Charley.” As with A Streetcar Named Desire, On the Waterfront was also nominated for 12 Oscars, winning 8, including Best Motion Picture, Best Director, Best Actor and Best Supporting Actress.

As great as these pictures were, it was Kazan’s next film that I regarded as his best. East of Eden, adapted from John Steinbeck’s novel, starred James Dean and Richard Davalos as brothers Cal and Abel Trask competing for their father’s affection and the love of one woman, Abra, played by Julie Harris. It features an unforgettable performance by Dean. In what was his first major film role, he portrayed the alienated youth so perfectly that every scene is emotionally charged, culminating in Cal’s heartfelt gift to his father, which is met with rejection.

- [1] Elia Kazan, William Baer, Elia Kazan: Interviews (2000), Univ. Press of Mississippi

- [2] Peter Lev, The Fifties: Transforming the Screen, 1950-1959 (2003), University of California Press

- [3] Ken Dancyger, The Director’s Idea: The Path to Great Directing (2012), CRC Press

Kazan’s direction is superb throughout, he brings us the shots needed to focus on the actors delivering these beautifully written lines and East of Eden doesn’t miss a single beat. Though Kazan would go on to direct other great classics such as Baby Doll (1956), Wild River (1960) and Splendor in the Grass (1961), it’s East of Eden that I’ll always remember as the film that made me want to seek out his other works – and I’m glad I did.

His contribution to American cinema has resulted in films we continue to study today in universities and fall in love with at movie houses that run them every so often. Without him his a director and co-founder of the Actors Studio, what I love the most about cinema would never have existed.

Patrick Samuel

The founder of Static Mass Emporium and one of its Editors in Chief is an emerging artist with a philosophy degree, working primarily with pastels and graphite pencils, but he also enjoys experimenting with water colours, acrylics, glass and oil paints.

Being on the autistic spectrum with Asperger’s Syndrome, he is stimulated by bold, contrasting colours, intricate details, multiple textures, and varying shades of light and dark. Patrick's work extends to sound and video, and when not drawing or painting, he can be found working on projects he shares online with his followers.

Patrick returned to drawing and painting after a prolonged break in December 2016 as part of his daily art therapy, and is now making the transition to being a full-time artist. As a spokesperson for autism awareness, he also gives talks and presentations on the benefits of creative therapy.

Static Mass is where he lives his passion for film and writing about it. A fan of film classics, documentaries and science fiction, Patrick prefers films with an impeccable way of storytelling that reflect on the human condition.

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA