Watership Down

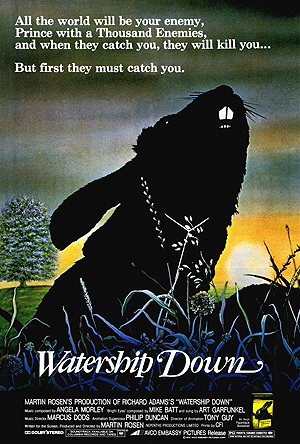

WATERSHIP DOWN (MOVIE)

Nepenthe Productions

Original release: October 19th, 1978

Running time: 92 minutes

Writer and director: Martin Rosen

Cast: John Hurt, Richard Briers

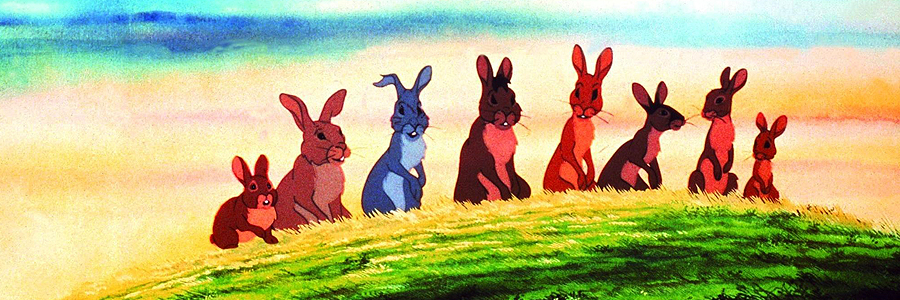

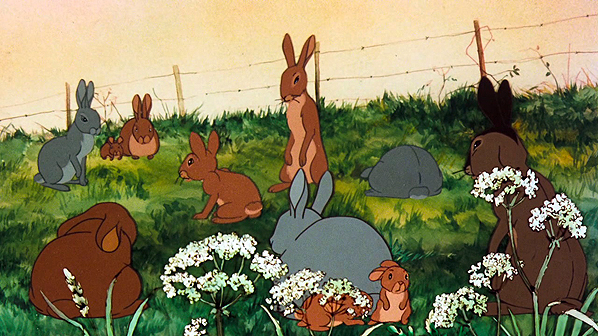

Let’s get this out of the way early. Watership Down isn’t really a children’s film. There are more than enough accounts of traumatized youngsters to attest to that. Parents be warned, don’t be fooled by the fluffy cover art. I can imagine there are rewards aplenty for the right child, but this is a bloody and starkly mythic rabbit odyssey that has ambitions beyond most animation.

Adapted from Richard Adams’ novel of the same name, the film makes clear its grand intent from the very first frame. We open into a creation myth that explains the spirituality of the rabbits that inhabit the world of Watership Down. Taking inspiration from the cave paintings of early man, the initial animation renders the story of how El-Ahrairah, the Prince of Rabbits, was granted the talents with which to evade his predators:

I was reminded of the Greek philosopher Xenophanes, a skeptical man who spoke suspiciously of how closely the gods resembled man. He mischievously suggested that should horses or cattle have gods they would take the form of horses or cattle. So it is with the rabbits of Watership Down who have an appropriately leporine theology that is separate and distinct from that of humans.

As the action moves to the present we meet Fiver (Richard Briers) and Hazel (John Hurt), two brothers – and rabbits – living in a warren somewhere in the English countryside. Fiver shows an almost clairvoyant level of intuition (a fitting exaggeration of that nervous rabbity edginess that comes with residing at the bottom of the food chain) and as a construction company rolls up he’s overcome by a sense of dread and foreboding. When his pleas to his warren elders fall on deaf ear he flees his home with a ragtag band of believers. The exodus quickly becomes a quest that has echoes in Homer and the Old Testament – with Fiver and his brother Hazel sharing the role of Moses.

The rabbit tribe begin to wander the country, using the talents gifted to El-

Ahrairah in order to dodge the threats posed by dogs, cats, badgers and gun toting farmers. Along the way they encounter a hutch full of does, imprisoned and ignorant of the world beyond their immediate perceptions. They seek shelter in a sparsely populated burrow whose well-fed population seems content to stick their heads in the sand and ignore the dark truth of their circumstance. Finally the wandering mob happen upon a brutally totalitarian burrow led by General Woundwort (whose name functions in the Dickensian fashion, instantly informing of his character) that leads to a ferociously violent face-off.

It would be easy to take passages of the film and point to specific moments in history. However, and perhaps it’s due to there being truth in the old maxim that history repeats itself, Watership Down’s strength lies in the way its ideas reverberate through the ages. The different warrens that litter the beautifully hand rendered countryside neatly function as counterparts to human nation-states. They allow for a powerful discussion of the individual and his relationship to the state as well as the nature and worth of freedom.

Watership Down is a film constructed almost entirely of moments of myth and allegory. Unfortunately the narrative often struggles to keep up, as the film jumps somewhat gracelessly from incident to incident – from idea to idea. Stuffed full to the  extent that the film threatens to burst at the seams, the rough stitching is often all too exposed. This gracelessness means that the story feels a little dense and overly compact, I found myself wishing that the filmmakers had left themselves a little more space to breathe.

extent that the film threatens to burst at the seams, the rough stitching is often all too exposed. This gracelessness means that the story feels a little dense and overly compact, I found myself wishing that the filmmakers had left themselves a little more space to breathe.

Whilst its gained a certain notoriety that stems from its bloodthirsty finale, there’s another moment for which the film has become known. Ask any given person what they remember of Watership Down and I would guess that a majority would cite Art Garfunkel’s rendition of Bright Eyes. Single-handedly earning the film its reputation as a tearjerker, I was surprised on my recent viewing by how poorly the song fits the films tone. Overly saccharine and accompanied by trippy visuals that emerge out of the blue, the moment feels unearned and ill fitting when set against the films grander ambitions.

When all is said and done, Watership Down is an animated feature that has more in common with Orwell’s Animal Farm than anything in the Disney stable. Animations critical stock has risen recently in the wake of films from Studio

Ghibli and Pixar, and the market for adult animation has grown since 1978. Uneven as it may be, this is a film that deserves its share of this new audience.

Thomas Grieve

Tom is a Cardiff University Philosophy graduate from sunny Manchester. He favours filmmakers with edge and ambition, ones unafraid to subvert and disturb the status quo. This means directors such as David Lynch, Paul Thomas Anderson, Stanley Kubrick, David Croenenberg and Terry Gilliam.

Usually found in front of a screen trying to catch up on an ever-expanding watch list he also occasionally finds time to write. He tweets once in a while too: @thomasgrieve .

© 2022 STATIC MASS EMPORIUM . All Rights Reserved. Powered by METATEMPUS | creative.timeless.personal. | DISCLAIMER, TERMS & CONDITIONS

HOME | ABOUT | CONTACT | TWITTER | GOOGLE+ | FACEBOOK | TUMBLR | YOUTUBE | RSS FEED

CINEMA REVIEWS | BLU-RAY & DVD | THE EMPORIUM | DOCUMENTARIES | WORLD CINEMA | CULT MOVIES | INDIAN CINEMA | EARLY CINEMA

MOVIE CLASSICS | DECONSTRUCTING CINEMA | SOUNDTRACKS | INTERVIEWS | THE DIRECTOR’S CHAIR | JAPANESE CINEMA